Three main forces that regulate your homeostasis and inner balance

When my son was a baby, he used to wake up several times per night. After putting him back to sleep, I would lie in my own bed, awake for hours, listening for sounds coming from his room. Eventually, I realized that this kind of alert listening prevented me from falling asleep. When I purposefully stopped listening, I was able to fall asleep much faster. Turns out, there is a reason for that. When you are in a sympathetic state (fight-or-flight mode), “the middle ear regulation shifts away from listening for human voice toward listening for low-frequency sounds of predators or high-frequency sounds of distress.”(1) Since I was intently listening for high-frequency sounds of baby crying, I was inadvertently putting myself into a sympathetic state, which made it very hard to fall asleep.

Although those days of newborn parenting now seem like a blur, I still remember myself fluctuating between total numbness from exhaustion, frenetic mobilization to get anything done, and peaceful, happy feelings of pure love. It turns out we reliably travel between those states on a regular basis, both within the space of one day and throughout our lives, and we have our autonomic nervous system to thank for that.

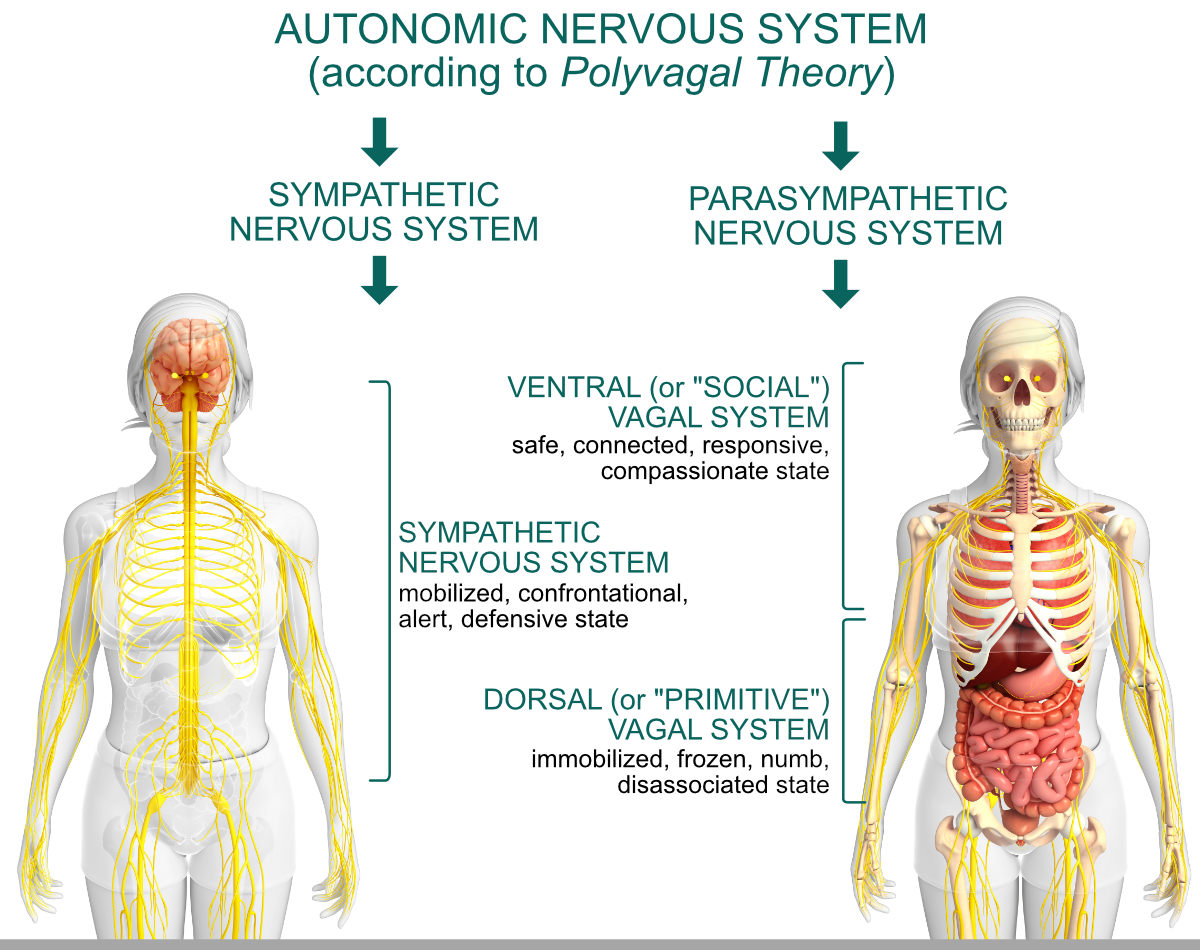

Your autonomic nervous system (ANS) is concerned with your survival during times of danger and thriving during times of safety. It constantly evaluates your external and internal environment for signs of danger and jumps to your defense before those signs even rise to the level of your conscious awareness. Even though we usually think of two branches of the ANS as the main driving forces that regulate your homeostasis and inner balance, there is a theory that suggests that there are actually three neurological pathways built into us that drive our physiological reactions.

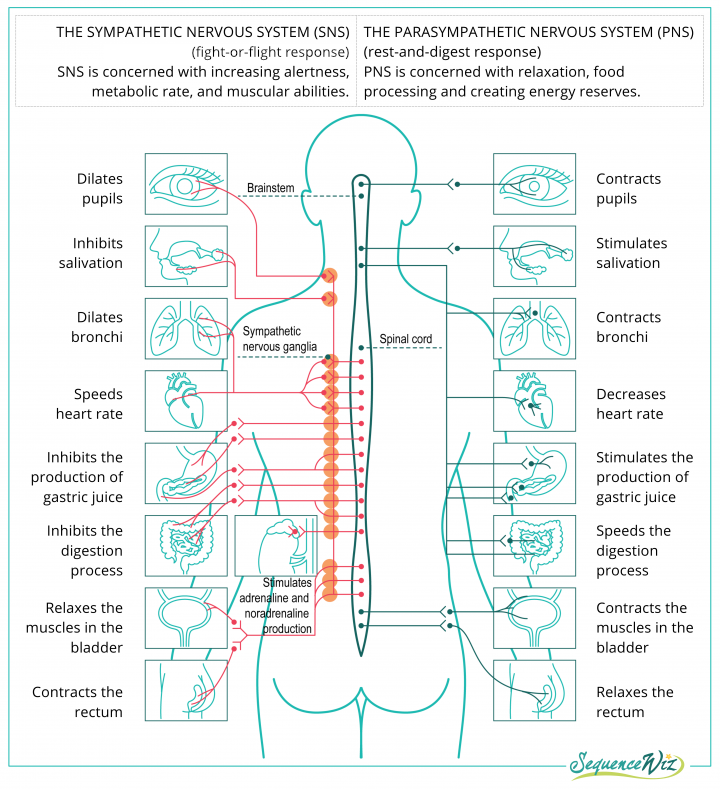

The autonomic nervous system is made up of two branches: the sympathetic and the parasympathetic. The sympathetic branch is a bundle of nerves that is found in the middle of the spinal cord. Those nerves connect to every major organ and initiate the fight-and-flight response throughout your entire system (dilating pupils, speeding up the heart rate and breathing, secreting adrenaline, and so on). We usually think of our sympathetic system as a gas pedal that gets you going. The parasympathetic branch is usually associated with rest-and-digest response and is essentially made up of the fascinating vagus nerve. It is usually described as a counterbalance to the fight-or-flight response that brings you back to the state of equilibrium. We usually think of it as a foot break that you press when you need to slow down and regroup.

However, the Polyvagal Theory pioneered by Dr. Porges takes it one step further. It looks at the entire autonomic nervous system through the lens of our essential needs for safety and connection to other human beings. The Polyvagal Theory stipulates that there are actually two kinds of “brakes” we have built into our systems—a regular “foot brake” and an “emergency brake,” and both of those brakes get activated by the vagus nerve under different conditions.

The vagus nerve is divided into two distinctive pathways that serve two very different functions. Those two branches of the nerve travel together from the brainstem and split at the level of the diaphragm: the dorsal vagus travels downward and affects the organs underneath the diaphragm, especially those regulating digestion, and the ventral vagus travels upwards and influences the heart rate and breathing rate, as well as regulates connections with facial nerves. Deb A. Dana, in her book “The Polyvagal Theory in Therapy,” writes that because of these unique pathways, “each autonomic state brings a characteristic range of responses though its own pattern of protection and connection.” (1)

Dorsal (or “primitive”) vagus activation (emergency brake) stops you dead in your tracks and makes you feel frozen, numb, or “not here.” Your system is drained, and your energy resources are being conserved through collapse and total shutdown. This happens when there is a major trauma or life threat (and in the aftermath of those) and when you feel completely exhausted or lost. This can be a consequence of illness, injury, or medical procedure on any organ below the diaphragm; it can manifest through impaired immune function, a chronic lack of energy, digestive issues, depression, and general withdrawal from social connections. This is a hypoaroused state (in yoga, we would call it a tamasic state).

The sympathetic system (gas pedal) gets activated when you need to take action. You are still searching for protection and safety, but in this state, you do it through the mobilization of your resources. Your entire body is on high alert and ready for action, which also means that you see, hear, and sense danger everywhere. When you are in a sympathetic state, you are more likely to initiate confrontation, misread facial clues, and less likely to connect to other people. This state can manifest as frenetic movement, busyness, fidgeting, and overall defensiveness. This is a hyperaroused state (in yoga, we would call it a rajasic state).

Ventral (or “social”) vagus activation (foot brake) encourages you to slow down and puts you in a state of safety and connection. Deb A. Dana writes: “In the ventral vagal state, we have access to a range of responses including calm, happy, meditative, engaged, attentive, active, interested, excited, passionate, alert, ready, relaxed, savoring, and joyful.”(1) In this state, you are most open to connection with others, the world seems like a welcoming place full of possibility, and you are able to feel compassion both toward yourself and others. “In the ventral vagal state, hope arises, and change happens.”(1) In this state, you feel safe and open to social connection (in yoga, we would call it a sattvic state).

This theory closely reflects the yogic idea of the three gunas (tamas, rajas, and sattvas) and demonstrates how gunas are reflected in your autonomic nervous system. Your autonomic nervous system is a foundation upon which your entire lived experience is built. Most of us move through those three states throughout the day in response to the sensations within the body and signals from the environment. Do we move through those states in a particular order? What impacts that transition? Do we have any conscious control over it? And what does it have to do with teaching yoga? We will discuss all those questions next time. Tune in!

Do we move through those states in a particular order? What impacts that transition? Do we have any conscious control over it? And what does it have to do with teaching yoga?

This exact thing has just happened to me following an operation that my husband had for colon cancer. I coped with his diagnosis, preparation for surgery, during his hospitalisation and helping him at home while he was so poorly.

After about 6 weeks when it looked as though he was going to make a good recovery, I collapsed while taking out our dog and continued to vomit (most unlike me) copiously in a kind gentlemans van who picked me up and returned me to my office. Very poorly and slept for several days.

How to stop this overload – I am a yoga teacher, have been practicing for over 30 years and thought I was taking things fairly easily …? there were no warning signs.

Olga,

That is absolutely the most coherent description of the Vagal system I have heard and I am so grateful. Our have totally illuminated it for me.

Thanks so much!

Mary

Dear Olga,

It’s very interesting subject. Thank you for bringing it up. Looking forward to next posts learning implications in yoga practice. Can we strengthen vagus nerve in the “right direction”. And how?

Thank you again

Galina

Wow, Jose Kirby’s comment makes me think of my body and mind’s reaction when I learned that my daughter was getting a divorce, it was a total emotional shock to me and quite unexpected. I was vomiting and totally wiped out for a whole afternoon, but recovered in the evening. Could this have been a vagus nerve reaction to really bad news?

Hi Maretta! I think it’s entirely possible. “The vagus nerve helps manage the complex processes in your digestive tract, including signaling the muscles in your stomach to contract and push food into the small intestine.” (Mayo Clinic website) If the dorsal vagal pathway was activated for you following the bed news, it is not unexpected that you would feel nauseous and wiped out.