How to keep your heart healthy by learning to unwind

Did you know that a horse’s heart is 17 times larger than an average human heart? If you stand next to a horse, your hearts would be on the same horizontal meridian, and when you are on a horse, your hearts would be on the same vertical meridian. And since the horse spends about 95% of its life in the parasympathetic (rest-and-digest) mode, it’s no wonder that you might feel calmer when you are near a horse (as long as you are not afraid of horses, of course). Some research shows that the human heart rate drops to the frequency of the horse’s, probably because the electromagnetic field of the horse’s heart is larger. I learned all those things in my introductory equine therapy lesson. It’s no wonder that equine therapy can help manage a variety of conditions, including anxiety and PTSD.

It is essential for our heart health to be able to switch to the parasympathetic mode regularly and completely. There is nothing wrong with sympathetic (fight-or-flight) activation as long as we don’t get stuck in it.

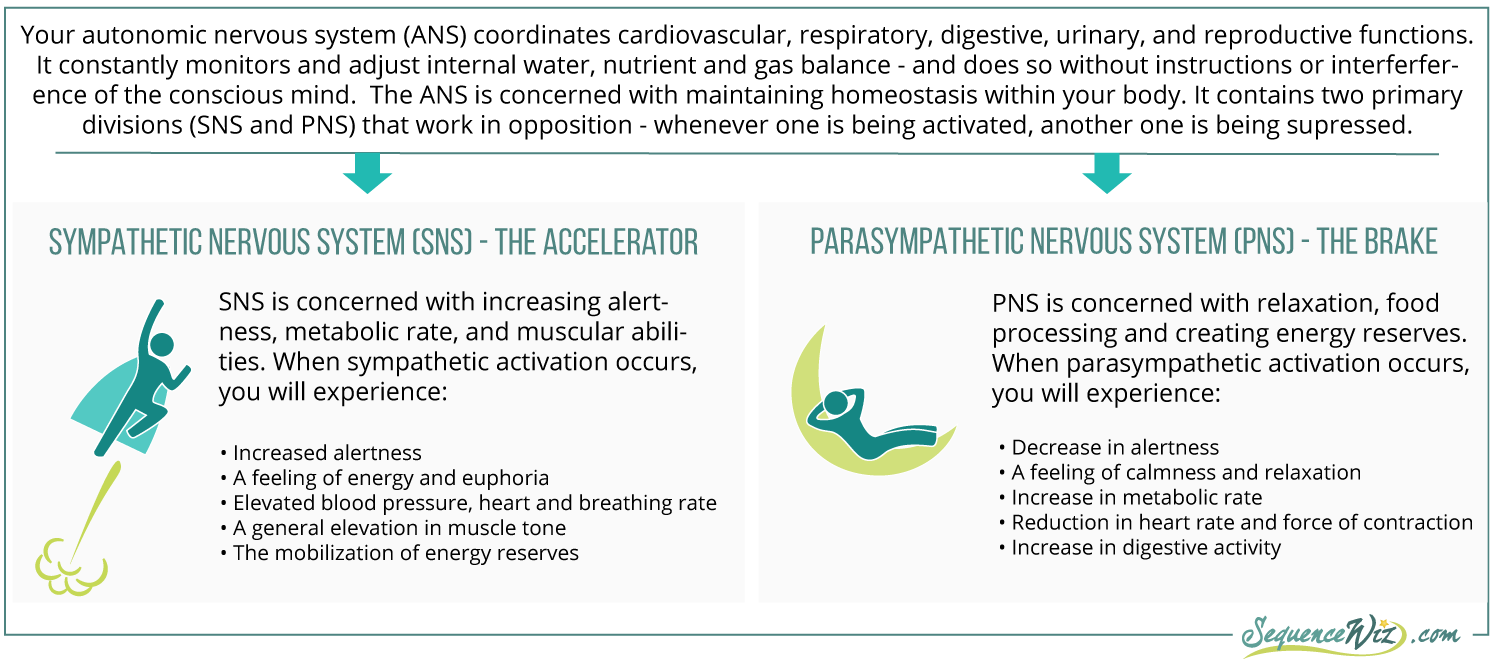

The sympathetic system gets activated whenever we need to mobilize our internal resources and rise to a physical or mental challenge. Our circulatory system responds to sympathetic activation by making the heart beat faster and stronger, increasing blood pressure and blood flow to the muscles, and raising blood volume. This mechanism is at play when you walk up a steep hill on a hike, go for a run, or do some other form of exercise that challenges you. These types of activities are good for you because they strengthen your heart and improve your circulation, which keeps all cells in your body properly nourished. The problems arise when we activate our sympathetic systems all the time about every little thing and then get stuck in that sympathetic activation instead of switching into the rest-and-digest mode (parasympathetic activation).

The sympathetic system gets activated whenever we need to mobilize our internal resources and rise to a physical or mental challenge. Our circulatory system responds to sympathetic activation by making the heart beat faster and stronger, increasing blood pressure and blood flow to the muscles, and raising blood volume. This mechanism is at play when you walk up a steep hill on a hike, go for a run, or do some other form of exercise that challenges you. These types of activities are good for you because they strengthen your heart and improve your circulation, which keeps all cells in your body properly nourished. The problems arise when we activate our sympathetic systems all the time about every little thing and then get stuck in that sympathetic activation instead of switching into the rest-and-digest mode (parasympathetic activation).

If you never leave the fight-or-flight (sympathetic) mode, your blood pressure will be chronically elevated. This is bad news for your cardiovascular system on several levels:

- The blood now courses through the blood vessels with more force, which makes them thicker (to control the blood flow). As a result, they become more rigid and more resistant to blood flow, which leads to a further increase in blood pressure.

- The blood returns to the heart with more force, slamming into the left ventricle. This can lead to the thickening of the left ventricle, which grows bigger. The heart is now lopsided, which increases the risk of developing an irregular heartbeat.

- The smooth inner lining of the tiniest vessels begins to tear. The immune cells migrate to the site and begin the repair process. This is accompanied by inflammation. All kinds of circulating gunk (cholesterol, fat, and others) can get stuck at the inflammation site, creating atherosclerotic plaque. “In the last few years, it is becoming clear that the amount of damaged, inflamed blood vessels is a better predictor of cardiovascular trouble than the amount of circulating crud. This makes sense, in that you can eat eleventy eggs a day and have no worries in the atherosclerosis realm if there are no damaged vessels for crud to stick to; conversely, plaques can be forming even amid “healthy “levels of cholesterol if there is enough vascular damage.” (1)

- Once the plaque is formed, an increase in blood pressure can tear it loose and send pieces of it floating around. As long as it travels along bigger blood vessels, it doesn’t cause any trouble. But if it ends up in a smaller vessel, it can clog it completely. Clogging a coronary artery leads to a heart attack, clogging up a blood vessel in the brain leads to a stroke.

Many things can go wrong with our cardiovascular system in response to chronic sympathetic activation. This just underscores the importance of being able to regularly switch into the parasympathetic mode, applying a metaphorical brake to our revved-up system. The parasympathetic switch is handled by our good old friend, the vagus nerve.

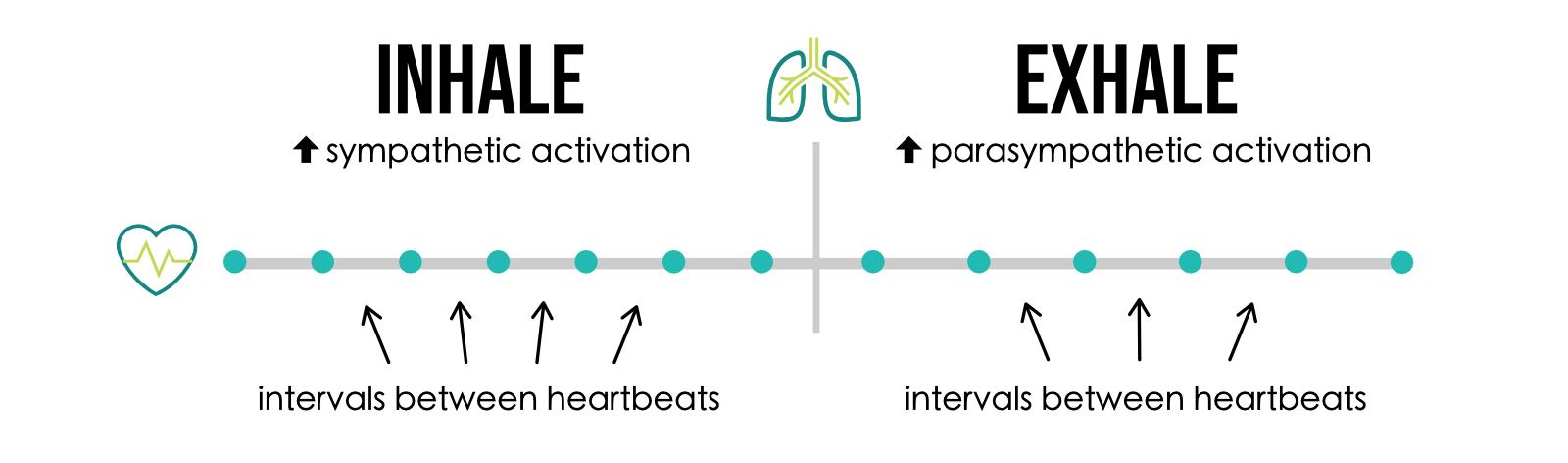

The vagus nerve is responsible for slowing our system down and switching it into the rest-and-digest mode. A clear indicator of how well the vagus nerve is doing this job is called the vagal tone, which can be measured by your cardiologist. Every time you inhale, your sympathetic nervous system gets slightly activated and your heart beats a little faster. Every time you exhale, your parasympathetic system gets activated and your heart beats a bit slower. Comparing the length between two heartbeats on inhale and two heartbeats on exhale shows your heart rate variability.

The greater the difference (variability) between those two intervals, the more effective and efficient your vagus nerve is. It means that your body can easily switch from fight-or-flight to rest-and-digest mode and vice versa. It reflects your resilience. “Research shows that a high vagal tone makes your body better at regulating blood glucose levels, reducing the likelihood of diabetes, stroke and cardiovascular disease. Low vagal tone, however, has been associated with chronic inflammation. One of the vagus nerve’s jobs is to reset the immune system and switch off the production of proteins that fuel inflammation. Low vagal tone means this regulation is less effective and inflammation can become excessive.” (2)

There are different ways you can try to activate your vagus nerve in your yoga practice in the moment and over time. But another important point that the heart rate variability shows us is how important it is to be able to switch from an active to restful mode frequently and completely. This applies not just to your heartbeat but to how you live your life. If the variability between your work and leisure time is low or nonexistent, you are much less likely to feel vital and resilient. If you keep stressing out even when engaging in activities meant to lower your stress levels, you are keeping yourself in a sympathetic state. Learning to vary your periods of activation with periods of complete rest and recuperation within the space of a day, week or year will help you run your physiology as nature intended – rising up to the challenge when necessary and recuperating as soon as the danger or challenge has passed. After all, this is why zebras don’t get ulcers and reside in the parasympathetic state most of the time – once the acute danger is gone, they are over it.

It is also important, of course, what kind of activities you choose to chill out. My dad, for example, had only two ways of unwinding – smoking and drinking. After forty-five years of abusing his body, we were saddened, but not surprised, when he passed away from a heart attack at the age of sixty-five. There is only so much our hearts can take. Generally speaking, choosing activities that move your body, nourish your soul, and don’t clog your arteries are much better for your heart. Horse riding can be one of those options if it appeals to you. And interestingly, your personality type and the emotions you most often experience are also connected to your heart health. We will talk about it next time.

Resources

1. Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers by R. Sapolsky (affiliate link)

2. Hacking the nervous system by Gaia Vince

Understand the major players (organs and tissues) within each physiological system and their function. Discover what can go wrong and how we can try to prevent it with the choices you make.

Thank you, Olga, for this informative and easy-to-follow explanation of our nervous system and the importance of learning to support vagal tone. I really appreciate all the time and care you take to educate us about our organs, our breath, our whole self!

Namaste,

Diane

Thank you Olga for such an interesting article. Look forward to hearing more in your next blog.

Thank you, Helen!

How many years have I been connected with horses, but I have never heard about finding our hearts with them on the same horizontal meridian! Thank you for sharing, a wonderful, interesting and informative article. Good luck!