Core players: The muscles that move your trunk and how to work them

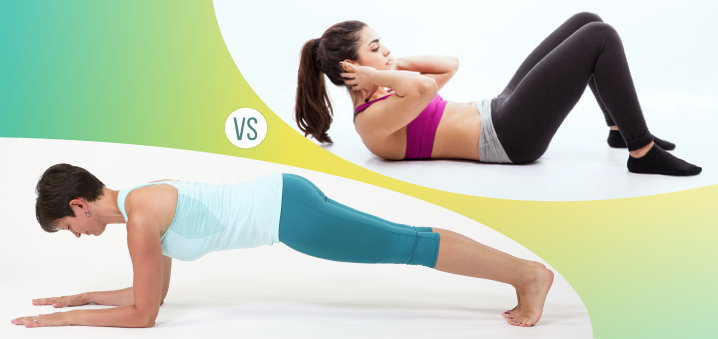

From my observations around my gym, it looks like abdominal crunches are on their way out, which is a good thing. It doesn’t mean that you should never do them; it just means that you shouldn’t do them exclusively.  An abdominal crunch primarily targets your rectus abdominis muscles (the infamous 6-pack), whose job is to flex your trunk forward. Unfortunately, you already flex your trunk forward all day long when you sit, drive, lean forward, or stand with your tailbone tucked under. Repetitive spinal flexion over time can mess up your natural lumbar curve, which repositions your spinal disks in relation to one another, creating compression on the discs in places where they are not supposed to be compressed.

An abdominal crunch primarily targets your rectus abdominis muscles (the infamous 6-pack), whose job is to flex your trunk forward. Unfortunately, you already flex your trunk forward all day long when you sit, drive, lean forward, or stand with your tailbone tucked under. Repetitive spinal flexion over time can mess up your natural lumbar curve, which repositions your spinal disks in relation to one another, creating compression on the discs in places where they are not supposed to be compressed.

Pete Egoscue writes: “Everybody wants a flat stomach, but the worst way to get one is to deliberately contract your abdominal muscles. This holds your hips and spine in flexion, preventing them from achieving neutral positions. Healthy abdominals are intended to work as back stabilizers, not prime movers.”(1) When it comes to the muscles of the core we need to create stability and balanced development between all the different layers.

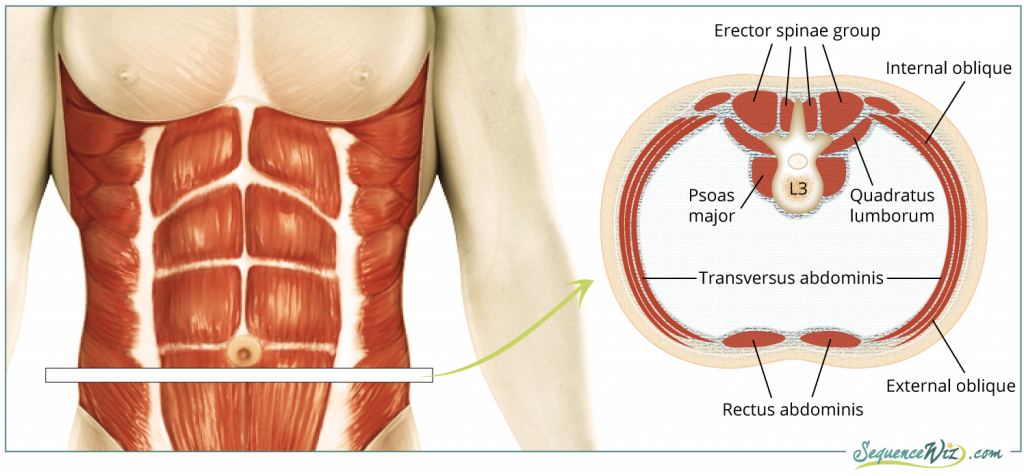

Before you can do anything to your core muscles, you need to develop core awareness. You can spend some time investigating the action of different muscle groups and their relationships with one another. After all, nothing in the body works in isolation. If you look at the cross-section of your abdomen at the level of the third lumbar vertebrae, you will see the following players that wrap around your abdominal content and enable the movement of the trunk. Each has a primary function, but they also help each other in many ways.

Transversus abdominis compresses abdominal contents and helps with overall core stability. This muscle is the deepest of the bunch and can be hard to feel. It plays a major role in forced exhalation, so if you want to feel it better, cough intentionally a few times. That is why when you are sick and cough a lot, those muscles can get sore or spasm, which can lead to back pain. To build awareness of your transversus abdominis, try this: Sit tall and take a deep breath. On the exhale, hug your waist in from the front, side and back at the same time, as if you were tightening the corset around your torso, on the inhale release. You can do that action in any yoga pose, and it will help you develop awareness and stability in your core.

The Rectus abdominis flexes the trunk. If you shorten the front of the body and round forward (just like you do in the abdominal crunch), you will feel it working. We shouldn’t do too much of that without balancing it out with other actions.

Erector spinae muscles extend the spine. Their job is to return the body into the upright position from the forward bend and bend backward. These are very important movements for most of us since we sit so much, making our backs weak and sore. The trick here is to make sure that every time you bend back, you distribute the curve throughout the lower back instead of pivoting at one point – that way, you will strengthen the muscles evenly. Using the arms to push yourself into the poses (like Cobra, for example) will interfere with strengthening your back muscles.

Internal and external obliques are hard to differentiate, even though they do slightly different movements. Every time you rotate your upper body, you will feel the muscles on one side of the torso stretching and the other side contracting. Obliques also bend your torso sideways (in this case, with the help of quadratus lumborum).

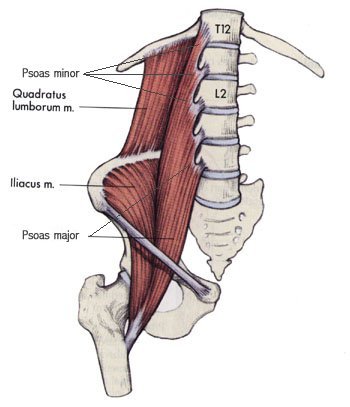

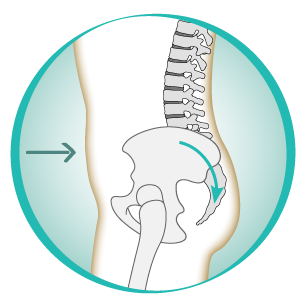

You will notice that psoas major is also present in the cross-section above. Although technically, it is considered a hip flexor, psoas (along with its buddy iliacus) plays an important role in lower back stabilization. After all, it connects your legs to your spine. It can get tight from prolonged sitting and excessive lumbar flexion and pull on your spine (more info about it here). I find that students (and teachers) often confuse psoas with rectus femoris, which is much closer to the surface than psoas. If you lift your knee and feel the muscle contracting right in the hip crease, this is not your psoas; it’s rectus femoris (which is part of your thigh muscles). Since both of them flex the hip, it’s a bit hard to feel one of them working without the other.

You will notice that psoas major is also present in the cross-section above. Although technically, it is considered a hip flexor, psoas (along with its buddy iliacus) plays an important role in lower back stabilization. After all, it connects your legs to your spine. It can get tight from prolonged sitting and excessive lumbar flexion and pull on your spine (more info about it here). I find that students (and teachers) often confuse psoas with rectus femoris, which is much closer to the surface than psoas. If you lift your knee and feel the muscle contracting right in the hip crease, this is not your psoas; it’s rectus femoris (which is part of your thigh muscles). Since both of them flex the hip, it’s a bit hard to feel one of them working without the other.

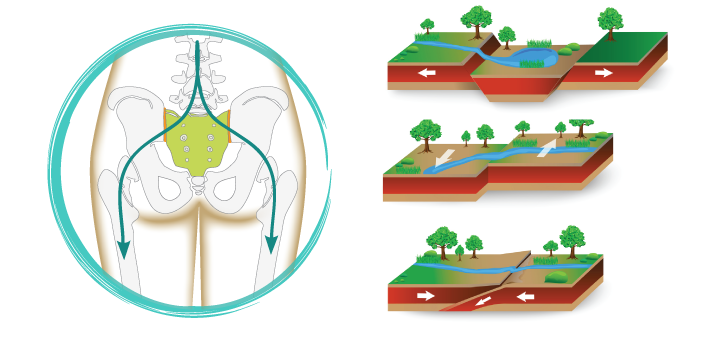

So these are the major players when it comes to your core musculature. If you are conscious of your movement during your yoga practice you probably involve most of those muscles as you bend forward and backward, turn and twist. Theoretically, if your yoga practice is balanced in terms of the directional movement of the spine, you shouldn’t worry too much about not working your core. However, one area that seems consistently lacking in many yoga practices is the way your collective core musculature (but transversus abdominis especially) affects the position of the pelvis. This is a fundamental idea that has a huge impact on the health and stability of your lower back, no matter which way you bend.

When we talk about developing and maintaining a healthy relationship between the pelvis and the spine, there are two main ways to approach it – “the pelvic tilt” and “the corset”.

References

1. Pete Egoscue Pain Free: A Revolutionary Method for Stopping Chronic Pain

Thanks Olga,

It is always enjoyable to read your blogs. Great graphics by the way. Keep the good work up.

Georgeanna

Thank you Georgeanna! 🙂

I welcome your insights and illuminations on safe Yoga practice. Seeing a new blog post from you is a treat.

The psoas flexes the hip and extends the spine. Thus a tight psoas results in a swayback posture and lack of hip extension. Psoas tightness can be caused by a prolonged seated position, which shortens it due to the hip being in a prolonged flexed position, but not by a flexed spine as stated in the article. Indeed spinal flexion coupled with hip extension elongates the psoas.

Hi Suzanne – I agree. I meant that movements like abdominal crunches, especially with legs raised can contribute to psoas tension.

As always Absolutely amazing article!

Nice article, thinking about the psoas and the core, i belive we have to make our core functional to keep the psoas in his role!!!! Other way we will moving from the toxic compensation of the psoas and having many problems with disc or lumbar pain. Some people with short psoas will go for hyperlordosis and the others with weak psoas will go into flat lumber curve. Wherever they moving , they need smart active core muscles to keep the psoas in his place!!!! And the smart is not just in repetitive core exercise , is in the posture, in the asana when we have to develope that core intelligent .

Some people belive that the psoas is the soul of the body or the second brain, but i belive is the root of the postural problems plus the unfuctional core .

Thanks a lot!!!!!