What is your optimal breathing rate and why it matters

Many of your body’s physiological processes have a rhythmic nature: your heartbeat, blood pressure, digestive peristalsis, breathing rate, and many others proceed in a pulsating (or wave-like) fashion. Each system has its own rhythm. For example, the normal respiration rate for an adult at rest is 12 to 16 breaths per minute, the normal heart rate is 60 to 100 beats per minute, and the normal blood pressure is less than 120/80 mm Hg. Occasionally, those physiological rhythms can become synchronized, which improves the system’s efficiency and has great health benefits. Today, let’s take a look at the rhythms of your circulatory and respiratory systems and how they affect one another. Is there anything we can consciously do to synchronize those systems?

All healthy animals and humans experience rhythmic fluctuations in heart rate and blood pressure. It is normal and desirable because it demonstrates that our systems are able to adjust to our activity levels, arousal, stress, and so on. One of those rhythmic fluctuations in blood pressure is called Mayer waves. Mayer waves are cyclic changes or waves in arterial blood pressure that occur spontaneously. They are caused by the activity of the autonomic nervous system and the vagus nerve. Mayer waves occur at a frequency of about 0.1 Hz, which translates into a 10-second cycle, 6 cycles per minute. This frequency is generally lower than the frequency of respiration.

Your heart rate fluctuates as well. It is called heart rate variability, and it describes the variation in time intervals between heartbeats. Higher heart rate variability (HRV) is more desirable because it reflects the resilience of your heart and its ability to adapt to physiological and environmental demands quickly. “Higher levels of HRV are indicative of a healthy heart and a marker of overall healthy physiological functioning. Low HRV, or less responsiveness to physiological needs, predicts mortality and morbidity and also occurs in depression, anxiety, and chronic stress.” (1)

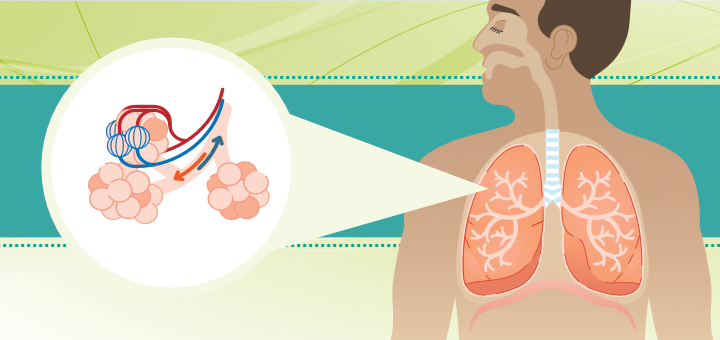

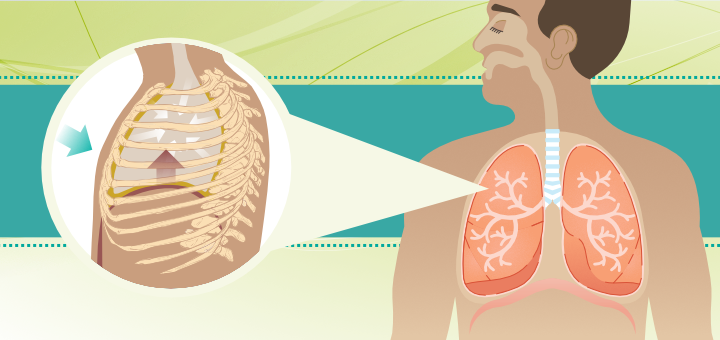

If higher heart rate variability is so important, is there a way for us to raise it? Turns out there is! Your heart rate variability is closely tied to your breathing and is at its highest when your heart rate and breathing synchronize. It is said that the heart rate and breathing become resonant. This resonance happens when you breathe with a frequency of 0.1 Hz, or about six breaths per minute. This is an average number, and it is not the same for everyone. “Each person has a unique resonance frequency (RF) breathing rate, ranging typically between 4.5 and 7.0 breaths/min. In studies of HRV biofeedback, the most common RF breathing rate is 5.5 breaths/min. […] When a person breathes at their identified RF breathing rate, heart rate and breathing become synchronized, and the highest levels of HRV are typically obtained.” (1)

Didn’t we mention the frequency of 0.1 Hz or 6 breaths per minute earlier? Remember Mayer waves in arterial blood pressure? Those blood pressure waves oscillate with the same frequency, which means that your blood pressure, heart rate, and respiration become synchronized at about 6 breaths per minute, or 10 seconds per breath. “A slow respiratory rate (6/min) has generally favorable effects on cardiovascular and respiratory function and increases respiratory sinus arrhythmia [reflection of higher parasympathetic or rest-and-digest activity], the arterial baroreflex [which helps to regulate fluctuations in blood pressure], oxygenation of the blood, and exercise tolerance. Slow respiration may reduce the deleterious effects of myocardial ischemia, and, in addition, it increases calmness and well-being. These effects result from, at least in part, synchronization of respiratory and cardiovascular central rhythms. A respiratory rate of around 6/min coincides with and thus augments the 10-second (6/min) Mayer waves.” (2)

If you dig deeper into the data, it appears that the oscillating rhythms of blood pressure, heart rate, and respiration synchronize at about 5.5-second inhalation and 5.5-second exhalation, which makes it about 5.5 breath cycles per minute. 5.5 seems to be the magic number of synchronized (or resonant) breathing. Now, that’s a tricky breath length to measure, so in our practice, we usually round it up to a 6-second inhale and a 6-second exhale. You have heard me begin our practices time and time again by asking you to deepen your inhalation and lengthen your exhalation to 6 seconds each. This way, we attempt to slow our breath and synchronize our internal rhythms. We also generally attempt to maintain this breath rhythm throughout the practice or use it as a jump-off point for more challenging breath work.

Once we achieve that cardio‐respiratory synchronization, how long does it last? Turns out there is another factor at play that makes the effects of synchronization more long-lasting. That factor is attention. A more recent study investigated the effect of slow breathing in combination with focused attention in yoga practice. Researchers concluded that “consistent results have been obtained, which highlight the importance of controlled low‐frequency breathing, which is ubiquitous and fundamental in delivering physiologically significant variations in heart rates of yogic practitioners. In addition, the results on focused attention group, […] have highlighted the contribution of the cognitive attributes like attention in achieving a sustained cardio‐respiratory synchronization. It has been observed that focused attention and low‐frequency breathing are co‐existing inherent strategies in yogic techniques which might play an important role in psycho‐physiologically adapting a nonpractitioner to get trained in yoga to derive long‐term physiological benefits.” (3) This study confirms that two main pillars that support effective yoga practice are slow breathing and attention.

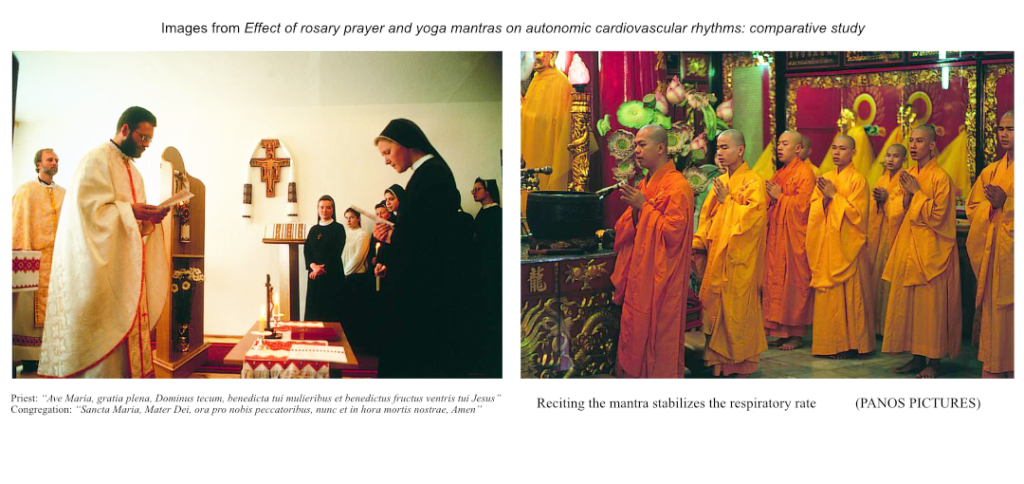

Turns out that combining slow breathing and attention to enhance people’s mental and physiological well-being is not a new idea for many religious traditions. Coincidently (or not), many prayers and mantras from around the world are also about 5.5 seconds long. For example, Leonardo Bernardi et al, studied the effect of rosary prayer and the Buddhist mantra Om Padme Om on autonomic cardiovascular rhythms. He writes: “The rosary is a repetition (50 times) of the Ave Maria, the whole 50 repeated three times. Each cycle, recited half by the priest and half by the congregation, is—in the original Latin—normally completed within a single slow respiration. We were surprised to find that each cycle (and break) of the Ave Maria (both “priest’s” and “congregation’s” parts, unrehearsed) took almost exactly 10 seconds.” (2) Another group of subjects recited Om Padme Om mantra in a call-and-response manner, which also took about 10 seconds per cycle.

After analyzing the results, the researchers concluded that “both the Ave Maria and the yoga mantra had similar effects, slowing respiration to around 6/min and thus having a marked effect on synchronization and also increased variability in all cardiovascular rhythms. This was seen not only in the respiratory signals but also in the RR interval, systolic and diastolic blood pressures, and in the transcranial blood flow signal. The spontaneous respiratory rate was 14.1 per minute during spontaneous breathing; it slowed down during free talking, and it slowed down further during the recitation of the Ave Maria and of the mantra, in both cases to close to the 6/min (10 s period) Mayer rhythm.” (2)

After analyzing the results, the researchers concluded that “both the Ave Maria and the yoga mantra had similar effects, slowing respiration to around 6/min and thus having a marked effect on synchronization and also increased variability in all cardiovascular rhythms. This was seen not only in the respiratory signals but also in the RR interval, systolic and diastolic blood pressures, and in the transcranial blood flow signal. The spontaneous respiratory rate was 14.1 per minute during spontaneous breathing; it slowed down during free talking, and it slowed down further during the recitation of the Ave Maria and of the mantra, in both cases to close to the 6/min (10 s period) Mayer rhythm.” (2)

Chanting or prayer recitation are proven methods of regulating the breath while anchoring one’s attention. Since the effect of cardiovascular and respiratory systems’ synchronization was so pronounced in the study of rosary prayer, the researchers went as far as writing: “We believe that the rosary may have partly evolved because it synchronized with the inherent cardiovascular (Mayer) rhythms, and thus gave a feeling of wellbeing, and perhaps an increased responsiveness to the religious message.” (2)

Curiously, chanting Yoga Sutra 1.2, which presents the definition of yoga (Yogah-chitta-vrtti-nirodhah), takes about 5.5 seconds as well, and the entire cycle (silent chanting on the inhale and out loud chanting on the exhale) takes about 11 seconds. This means that you can use this sutra to measure your breath instead of counting both during your daily activities and during your yoga practice. Using a yoga sutra or mantra in your yoga practice has additional benefits of working with sound, which can further affect your autonomic nervous system and vagal tone, and has all sorts of other positive effects on your system.

Your whole worldview is based on how you feel inside, which is mostly based on how your mind had interpreted your physiological state. The key to living a happier, more balanced life (even in the middle of a pandemic) is to keep your physiology in balance and to become better at interpreting the cues from your body.

References

- The Impact of Resonance Frequency Breathing on Measures of Heart Rate Variability, Blood Pressure, and Mood

by Patrick R. Steffen, Tara Austin, Andrea DeBarros, and Tracy Brown - Effect of rosary prayer and yoga mantras on autonomic cardiovascular rhythms: comparative study

by Luciano Bernardi et al. - An investigation on the influence of yogic methods on heart rate variability

by Sengottuvel Senthilnathan et al. - Breath: The New Science of a Lost Art by James Nestor