Should we take the body to the maximum bend possible in every direction possible?

A few months ago, one of the teachers in my yoga teacher Facebook group asked if it would be a good idea to go straight from Camel pose to Hare pose. Apparently, she had attended a class where this was taught.

In response, all sorts of opinions were posted—most teachers did not see a problem, and some suggested a “neutralizing twist” in between. We have already discussed why the twist by itself is not the best in terms of compensation for back bends or side bends. Here, we come across a slightly different issue that concerns your neck (nobody mentioned it in the comments to the original question, which was very surprising to me).

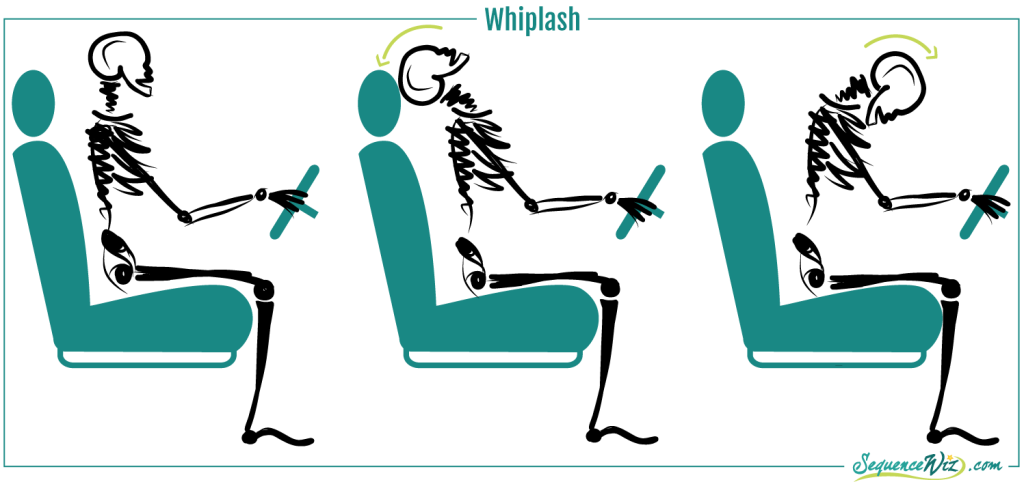

On the surface, following Camel pose with Hare pose appears legit – we are using a strong forward bend (Hare pose) to compensate for the deep back bend (Camel pose) – so, basically, after bending one way, we bend the other way. But once we look closer, we can see a very specific area of accumulated stress – the neck. In the Camel pose, your head is usually held all the way back (hyperextension), challenging the cervical spine and the neck muscles that support it. In the Hare pose, your neck is bent all the way forward (hyperflexion) with WEIGHT APPLIED TO IT. You go from one extreme to another – from deep cervical extension to fixed cervical flexion. This is almost like a slow equivalent of a whiplash from a car accident.

In fact, one of the quotes that I absolutely love is from Mary McInnis Meyer (yoga teacher and a former automotive engineer). “Bend it all the way one way, then all the way the other way, repeat . . . this is how you test structural products to simulate the most extreme conditions to make them break,” she says. We have no interest in doing that to our cervical spines, right?! The neck is the most mobile part of the spine, which makes it the least stable. We need to be very mindful when we place it in extreme positions like that. At the very least, we need to give your neck a chance to regroup and release the stress of one movement before going to the next.

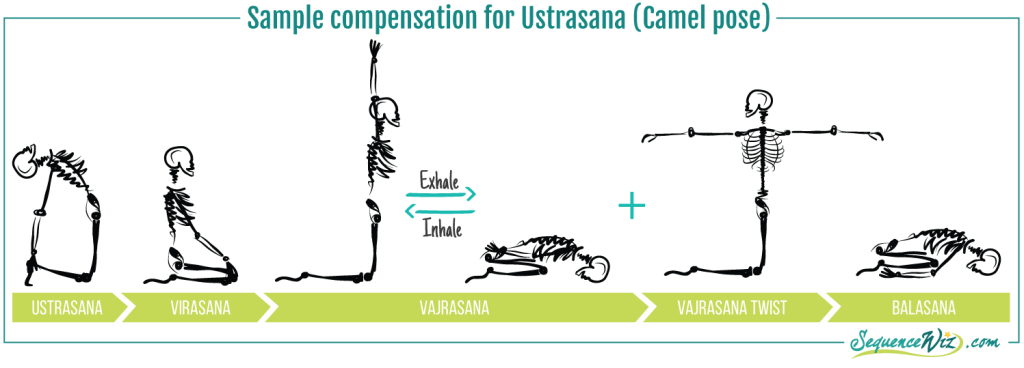

How do we do that? First, we need to get the neck into a neutral position by coming out of Camel pose and getting into Virasana. After a few breaths there, we can do Vajrasana to release the stress in the neck, upper back, and lower back and mobilize the neck and shoulders. We can even add a twisting adaptation afterward to loosen up the neck and upper back some more. Afterward, I would personally go into Child’s pose to rest the neck for a while and then continue with the practice. But if you REALLY wanted to do the Hare pose (and had a good reason for it), you could do it after Child’s pose. And then, of course, you would have to compensate for it afterward.

This is also why, in my tradition, we never use Fish pose to compensate for Shoulderstand. Going from a loaded cervical flexion (in Shoulderstand) to a fixed cervical extension (in Fish) is stressful for the neck. A better solution is to first rest your neck in a neutral position and then do some Cobras to engage the muscles on the back of the neck and upper back (read more about it here).

Those examples seem to reflect a common idea that often pops up in yoga classes – let’s take the body to the maximum bend possible in every direction possible. Why?! To quote Jozef Wiewel, who left a comment on my post last week: ” The spine is quite capable of moving outside its comfort zone, especially when we use our arms to get ourselves deeper into a posture, and will not always warn the practitioner directly of its risks and/or consequences. I believe it is one of my tasks as a teacher to point out that these risks are genuine and always emphasize that your spine is not interested in deep or far. Your spine is very happy with movement, though!”

This is something that we need to always remember when designing practices that take the spine through the maximum range possible. The risks are real. The rewards are questionable. The choice is ours.

I just had this conversation in a class. We were talking about people new to yoga who have great strength (often men) and the danger of using that strength to force the spine ( or anything) into twists or bends in any direction.

Thanks for this article and the time you put into presenting your ideas and knowledge. Very much appreciated!

Thank you Annie! Happy to hear that we are on the same page!

We just talked about this as well during teacher training and how a lot of teachers cue to hook your elbow onto your knee to twist further. we should use our core to twist and not our arms as it’s potentially dangerous to twist too deep when your body is not ready to go there.

Thank you Olga!!

You are so welcome Julia! It’s an important issue for me 🙂

Another great post Olga. Thanks!

It does not seem correct and fair to me to compare a car crash to a yoga pose ie camel to hare. For myself I would expect that to be a possible sequence that would be beneficial, although I understand that people’s neck flexibility is subject to variation and I have a flexible neck in extension and flexion. It also depends on how gently or violently the movements are followed. It also seems helpful to encourage mobility by including twists.

I often use the hare pose as a follow through from headstand where there is substantial pressure on the cervical vertebrae (as occurs in the camel) and the hare pose is quite releasing to practice as a counterpose.

Good Post… I make the students to “preparation of the Fish pose after the Plough” by makin them to lie supine with elbows on the floor. They will perfom forward- backward movement to Neutralize the neck. And later the Fish will be done