What baboons can teach us about stress-coping styles and heart health

Robert M. Sapolsky, a professor of biology and neurology at Stanford University, has been escaping to the Serengeti in Africa to study baboons in their natural habitat for over two decades. He believes that these baboons, who live in packs, work for about four hours a day and have the rest of daylight hours to socialize and be nasty to each other, represent humans perfectly. Sapolsky writes: “We are ecologically buffered and privileged enough to be stressed mainly over social and psychological matters. […] If a baboon in the Serengeti is miserable, it is almost always because another baboon has worked hard and long to bring about that state. Individual styles of coping with stress appear to be crucial.” (1)

Chronic stress (in baboons and humans) is caused by the constant activation of the sympathetic nervous system. We discussed how this ongoing sympathetic activation raises blood pressure and causes all sorts of other problems within our cardiovascular systems. Various studies conducted on baboons and other primates show that there are two ways that a primate’s personality style might contribute to heart trouble and other stress-related diseases. “In the first way, there is a mismatch between the magnitude of the stressors they are confronted with and the magnitude of their stress response–the most neutral of circumstances is perceived as a threat, demanding either a hostile, confrontational response or an anxious withdrawal. […] In the second style of dysfunction, the animal does not take advantage of the coping responses that might make the stressor more manageable–they don’t grab the minimal control available in a tough situation, they don’t make use of effective outlets when the going gets tough, and they lack social support.” (1)

To summarize, the risk of stress-related disease is increased for baboons who get “worked up” about something minor by either becoming hostile or anxious, particularly if they habitually fail to employ stress-coping strategies. It works the same for humans.

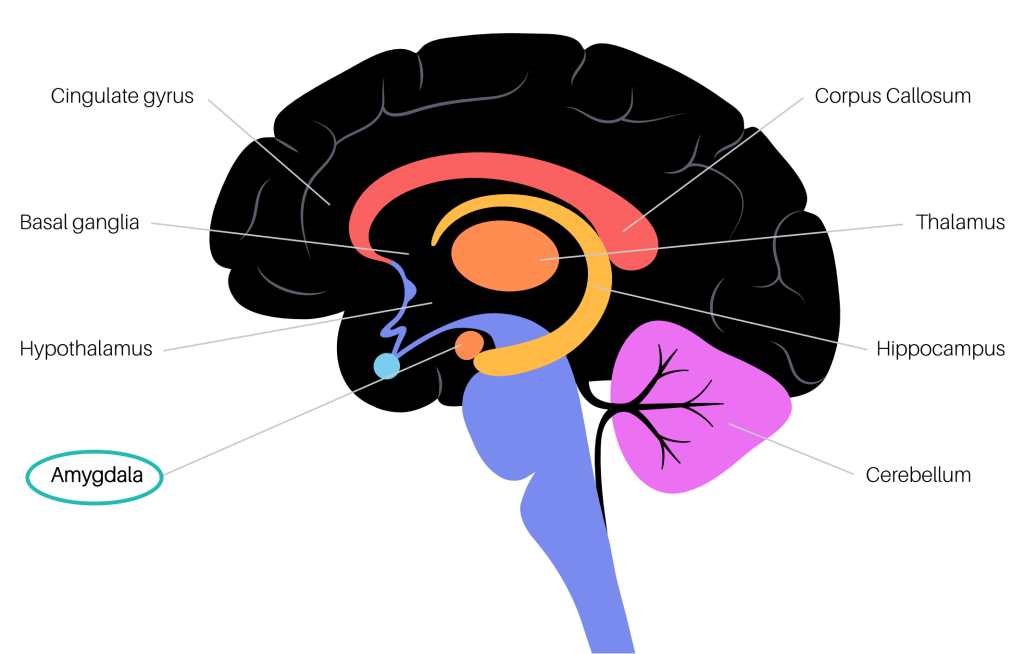

Getting “worked up” about real and imaginary threats is the job of the amygdala, a small, almond-shaped area deep inside the brain. Amygdala is involved in processing intense emotions, such as anxiety and fear; it also triggers anger and hostility. Amygdala activation is useful when dealing with an acute threat, but when this activation becomes chronic, it can lead to all sorts of problems. For example, this study found that heightened activity in the amygdala was linked to increased bone-marrow activity, inflammation in the arteries, and a higher risk of heart attack and other cardiovascular events.

Getting “worked up” about real and imaginary threats is the job of the amygdala, a small, almond-shaped area deep inside the brain. Amygdala is involved in processing intense emotions, such as anxiety and fear; it also triggers anger and hostility. Amygdala activation is useful when dealing with an acute threat, but when this activation becomes chronic, it can lead to all sorts of problems. For example, this study found that heightened activity in the amygdala was linked to increased bone-marrow activity, inflammation in the arteries, and a higher risk of heart attack and other cardiovascular events.

Fear, anxiety, and anger are qualitatively very different. Fear is the vigilance and the need to escape something real; it is necessary for our survival. Anxiety is about dread and foreboding, imagining the worst scenarios. People prone to anxiety overestimate risks and the likelihood of a bad outcome. Anger usually arises when there is a mismatch between what we’ve come to subconsciously expect and the hand we’re dealt in things big and small.

Both anger and anxiety are rooted in cognitive distortion. While anxious, we perceive the world as full of perpetual stressors, and the only hope for safety is to worry, foresee, and prepare for each one. While angry, we perceive the world as hostile and full of perpetual aggravations, and the only hope for safety is to threaten or attack first.

Numerous studies show that living our lives in a state of chronic anxiety or chronic hostility is not healthy for the heart (and other physiological systems). This reflects the fact that an ongoing sympathetic activation wears our bodies down. And it appears that this psycho-emotional impact can be community-wide.

A curious recent study analyzed millions of tweets sorted by county in the US from where they originated. Researchers were wondering if the use of negative language on Twitter could predict heart disease mortality from atherosclerotic heart disease (AHD). They found that “language patterns reflecting negative social relationships, disengagement, and negative emotions—especially anger—emerged as risk factors; positive emotions and psychological engagement emerged as protective factors. Most correlations remained significant after controlling for income and education.” What’s remarkable is that negative Twitter language predicted AHD mortality significantly better than a model that combined ten common demographic, socioeconomic, and health risk factors, including smoking, diabetes, hypertension, and obesity. Researchers concluded that “capturing community psychological characteristics through social media is feasible, and these characteristics are strong markers of cardiovascular mortality at the community level.” This study demonstrated that the level of hostility in our immediate community affects our heart health.

What can we do to pull ourselves out of that toxic brew of our own or our community’s making? We can do the exact same things that baboons do to relieve their stress and switch off the sympathetic activation:

- Reestablish some level of control over parts of the situation. That is why in our yoga teaching, we focus on consistently showing our students that they can change how they feel through their actions.

- Regularly engage in activities and behavior that reliably evoke parasympathetic activation. It can be walking for some, painting for another, cleaning or praying for somebody else–any activity that makes you feel peaceful and content will work.

- Establish and maintain meaningful social connections. “You are the company you keep” in more ways than one. Hanging out with toxic people is just as contagious as spending time with inspirational ones. Being deliberate in our choices and then putting effort into those selected relationships helps us regulate our physiology and keep our hearts healthy.

There are other things we can do to develop a better theoretical understanding and intuitive awareness of what’s going on within our various physiological systems; we will talk about it next time.

Get additional yoga practices for the cardiovascular system and many other yoga videos for skeletal, respiratory, digestive, nervous, and immune systems in the Zoom In Within yoga series.

References

- Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers: The Acclaimed Guide to Stress, Stress-Related Diseases, and Coping by Robert Sapolsky (affiliate link)

Another super interesting and helpful piece, Olga. Thank you for brightening my Wednesday!

I am a regular reader of this blog. And, I can’t thank you enough for what you share in your posts. It helps me personally, as well as in my teaching. Thank you!