The mechanics of exhalation and the preferred way to exhale in yoga

Normal unconscious exhalation is a passive process, as one simply relaxes the muscles that were engaged on the inhale. However, in our yoga practice, we purposefully augment the natural process of exhalation with intentional muscular engagement to lengthen the breath and create better structural stabilization in yoga poses.

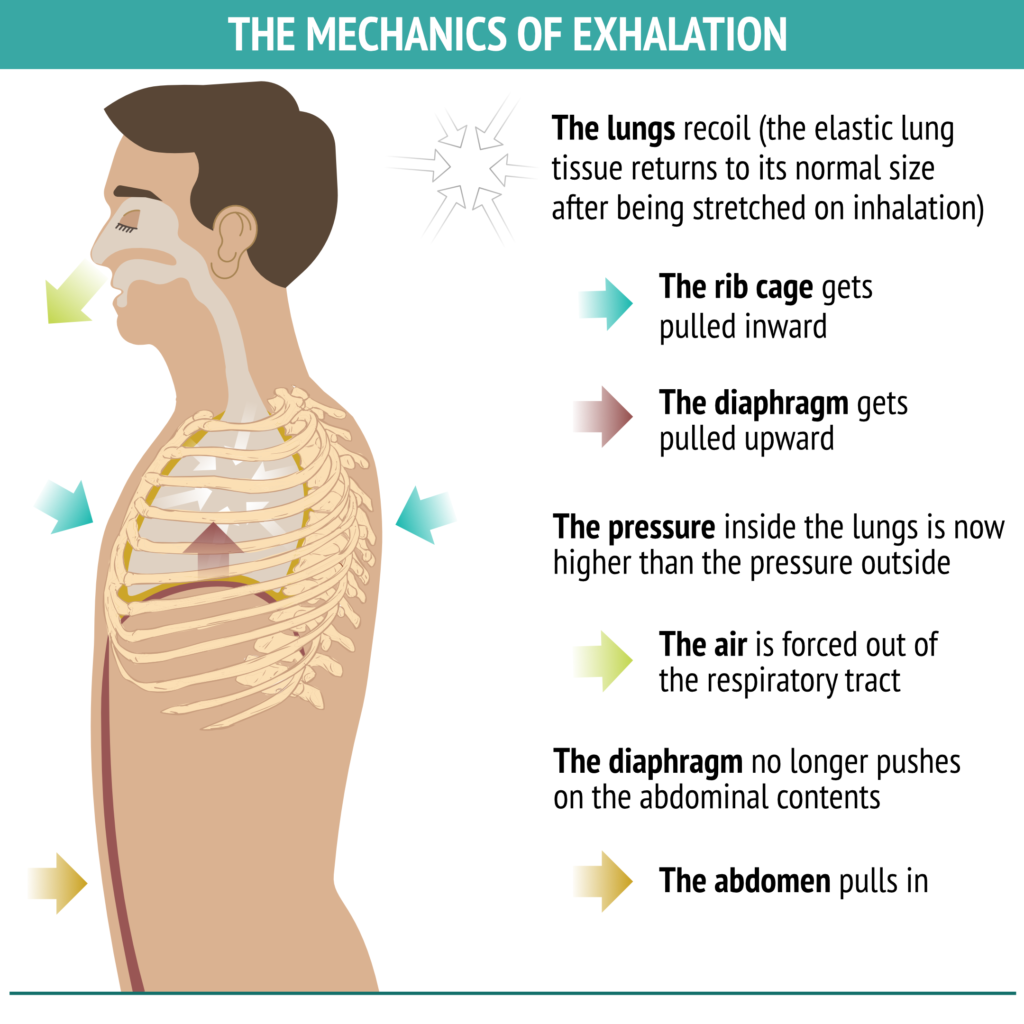

First, let’s take a look at what happens physiologically when you breathe out:

- The lungs recoil (the elastic lung tissue returns to its normal size after being stretched on inhalation),

- The thoracic cage gets pulled inward by the elastic recoil of the lungs,

- The diaphragm gets pulled upwards by the elastic recoil of the lungs,

- The belly pulls in as the abdominal contents get rearranged with the upward movement of the diaphragm.

This is what happens with passive exhalation. When you are at rest, you breathe in and breathe out about 0.5 liters of air with every breath cycle, and your diaphragm moves down and up about 1-2 cm (0.4 – 0.8 inches). When you control your breath intentionally, your breathing volume can increase to 6 liters with every breath cycle, and your diaphragm can move down and up about 10 cm (~ 4 inches). Increasing your breathing volume helps increase your vital lung capacity and improve the tonicity of your diaphragm.

You can intentionally deepen your inhalation by flaring out your bottom ribs and expanding your belly. You can intentionally lengthen your exhalation and make it more controlled by engaging the muscles of your core. There are three main mechanisms to do it.

- Thoracic exhalation moves your ribs down and shrinks your thoracic cavity by using your internal intercoastal and transversus thoracis muscles. This type of breathing is sometimes used during voice training, but it can lead to an exaggerated curve of the thoracic spine. We usually do not use this type of exhalation in yoga.

- “Corset” exhalation (or “hugging the waist in”) is accomplished by engaging the transverse abdominis muscle. It creates a corset-like contraction around the torso, which helps with lumbar spine stabilization, so we use it often in yoga poses that require extra lower back support.

- “Zip-up” exhalation (or “progressive abdominal contraction”) involves contracting the muscles of the abdomen successively from the pubic bone toward the navel. This type of contraction compresses the abdomen and forces the diaphragm up. It strengthens and stabilizes the lower part of the trunk and provides support for the lumbar spine.

In addition, you can include intentional engagement of the pelvic floor muscles with either the “corset” or “zip up” exhalation if you want to facilitate coordination between the pelvic floor and abdominal muscles, strengthen your pelvic floor or facilitate spinal stabilization.

The “corset” exhalation (or hugging the waist in) usually works well in poses that require abdominal support without changing the position of the pelvis. We usually use it for the purpose of creating stability in the lumbar spine. The “zip up” exhalation works well with the pelvic tilt, which is usually done to develop and maintain mobility in the lumbar spine. Check out this post for more detailed information about the differences between these two actions.

In the viniyoga tradition, the default pattern for exhalation is progressive abdominal contraction from the pubic bone toward the navel. We use this pattern of exhalation because it:

- Helps to lengthen the exhale

- Stabilizes the relationship between the pelvis and the spine

- Helps improve the tonicity of the diaphragm

- Creates more structural stability in the core

- Follows the intuitive flow of exhalation up and out

- Facilitates the upward movement of Apana

- Works well with the preferred method of inhalation (chest to belly).

We usually use this type of exhalation for the duration of the entire yoga practice unless there are specific instructions to do something different (for example, to exhale passively or to engage “the corset”). There is no need to actively engage your abdomen on exhalation when you are just going about your daily life, but it is still useful to keep your exhalation long. How can we control the length of our exhalation without abdominal engagement? We do it by restricting the flow of air through the throat by narrowing it. You probably know this type of breathing as Ujjayi breath. An important point to remember is that Ujjayi breath doesn’t have to be loud. The main point of this technique is to create a valve in your throat that restricts the flow of air so that it doesn’t escape too quickly. You can make your Ujjaiy breath very quiet and very soft while still controlling the airflow.

Moving with the breath in your yoga practice and taking time to observe and regulate your breath throughout the day can give you both a sense of inner spaciousness and show you that you have some control over your physical and mental state.

Thank you for your post.

The mechanics of exhalation and breath control is a very interesting subject. I am told that soon MRI technology will become sophisticated enough to record the contraction and relaxation of the smooth muscle of the airways (trachea, bronchi and sub bronchi) in real time. I strongly believe that this new technological window into the mechanics of breathing will explain through medical science, the physiological reasons behind the health benefits of Yoga breathing practices.