Dual roles of your diaphragm and why they are essential in your yoga practice

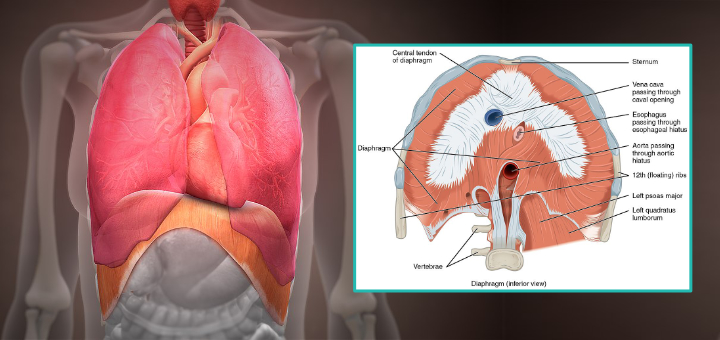

A diaphragm is the primary muscle of inhalation; it is responsible for about 75% of the air movement in normal breathing at rest (external intercostal muscles are responsible for the other 25%). The diaphragm is a very thin muscle shaped like an irregular dome. It has a fibrous middle part called the central tendon; muscle fibers radiate from that center in a beam-like fashion. These fibers attach to the internal outline of the ribcage all around. The diaphragm contracts like any other muscle and can be controlled voluntarily.

Your diaphragm separates your thoracic and abdominal cavity, but at the same time it connects those two cavities during the process of respiration and the action of spinal stabilization. Understanding both of those functions is essential in our yoga practice, so let’s take a close look at how they work.

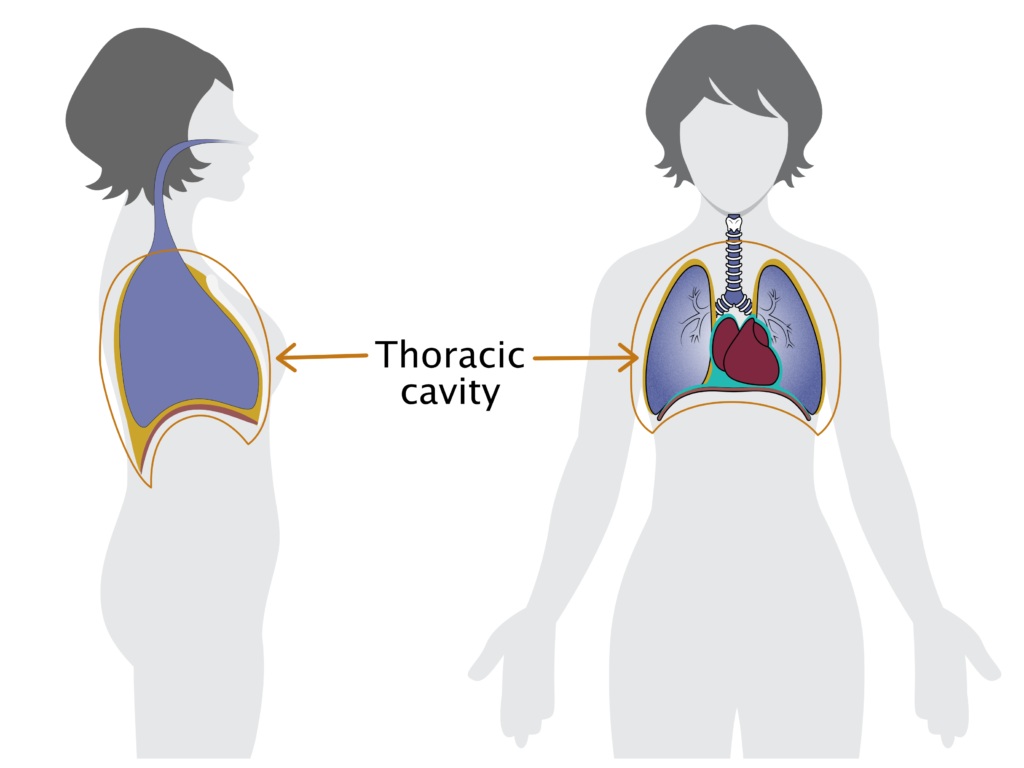

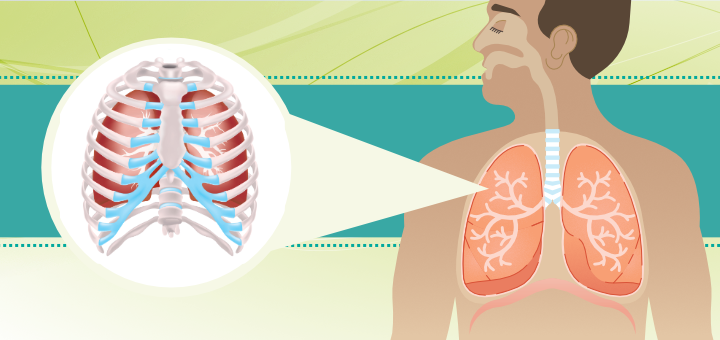

Your thoracic cavity is contained within your ribcage (top and sides) and your diaphragm (bottom). It consists of your lungs, pulmonary tissue, and heart.  As we discussed last time, your lungs are both compliant (can be stretched) and elastic (want to recoil). The outer surface of your lungs sticks to the inner surface of your ribcage and the top part of your diaphragm. On the inhale, your diaphragm contracts and moves down, and your rib cage expands. Both of those actions pull on your lungs, causing them to expand and suck in air. On the exhale, your lungs recoil and pull your diaphragm upwards and rib cage inwards. Meanwhile, your heart sits in a thin sac called the pericardium; it is wrapped in connective tissue that blends into the fibers of your diaphragm. As your diaphragm moves down and up with every breath, your heart rides down and up with it, 50,000 + times per day. It’s no wonder that cardiac function is closely linked to lung function.

As we discussed last time, your lungs are both compliant (can be stretched) and elastic (want to recoil). The outer surface of your lungs sticks to the inner surface of your ribcage and the top part of your diaphragm. On the inhale, your diaphragm contracts and moves down, and your rib cage expands. Both of those actions pull on your lungs, causing them to expand and suck in air. On the exhale, your lungs recoil and pull your diaphragm upwards and rib cage inwards. Meanwhile, your heart sits in a thin sac called the pericardium; it is wrapped in connective tissue that blends into the fibers of your diaphragm. As your diaphragm moves down and up with every breath, your heart rides down and up with it, 50,000 + times per day. It’s no wonder that cardiac function is closely linked to lung function.

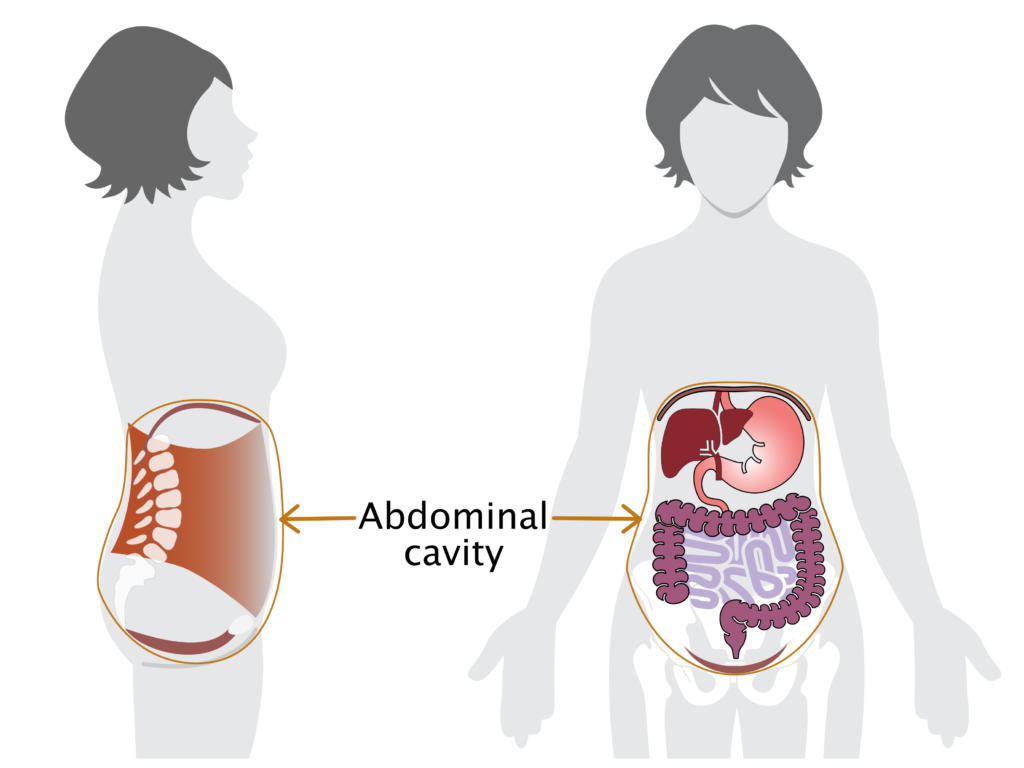

Your abdominal cavity is formed by your spine (back), abdominal muscles (front and sides), diaphragm (top), and pelvic floor (bottom).  The abdominal cavity contains soft and squishy abdominal organs. You can think of them as water balloons – if you squeeze them, they change their shape, but they cannot be compressed. Your abdominal cavity is full of those water balloon-like organs that slide and press against one another. Your diaphragm drapes over your abdominal organs and connects to the stomach and liver via the peritoneum (a serous membrane that wraps the organs). The diaphragm also touches your kidneys, spleen, pancreas, abdominal aorta, and parts of the large intestine. This means that every time your diaphragm moves down on inhale, it presses on one or several of those organs and changes their shape and position. The contents of your abdominal cavity shift and need to protrude somewhere. That is why your belly usually sticks out on inhale. Remember, you cannot compress the contents of your abdominal cavity, only rearrange it. If you hold your belly tight on the inhale, your diaphragm won’t be able to move much, and more pressure will be applied to your pelvic floor muscles. As this downward pushing action happens with every inhalation, your pelvic floor muscles need to be toned enough to withstand that pressure and support your abdominal organs. Your pelvic floor muscles help regulate intra-abdominal pressure that is created by the downward movement of the diaphragm.

The abdominal cavity contains soft and squishy abdominal organs. You can think of them as water balloons – if you squeeze them, they change their shape, but they cannot be compressed. Your abdominal cavity is full of those water balloon-like organs that slide and press against one another. Your diaphragm drapes over your abdominal organs and connects to the stomach and liver via the peritoneum (a serous membrane that wraps the organs). The diaphragm also touches your kidneys, spleen, pancreas, abdominal aorta, and parts of the large intestine. This means that every time your diaphragm moves down on inhale, it presses on one or several of those organs and changes their shape and position. The contents of your abdominal cavity shift and need to protrude somewhere. That is why your belly usually sticks out on inhale. Remember, you cannot compress the contents of your abdominal cavity, only rearrange it. If you hold your belly tight on the inhale, your diaphragm won’t be able to move much, and more pressure will be applied to your pelvic floor muscles. As this downward pushing action happens with every inhalation, your pelvic floor muscles need to be toned enough to withstand that pressure and support your abdominal organs. Your pelvic floor muscles help regulate intra-abdominal pressure that is created by the downward movement of the diaphragm.

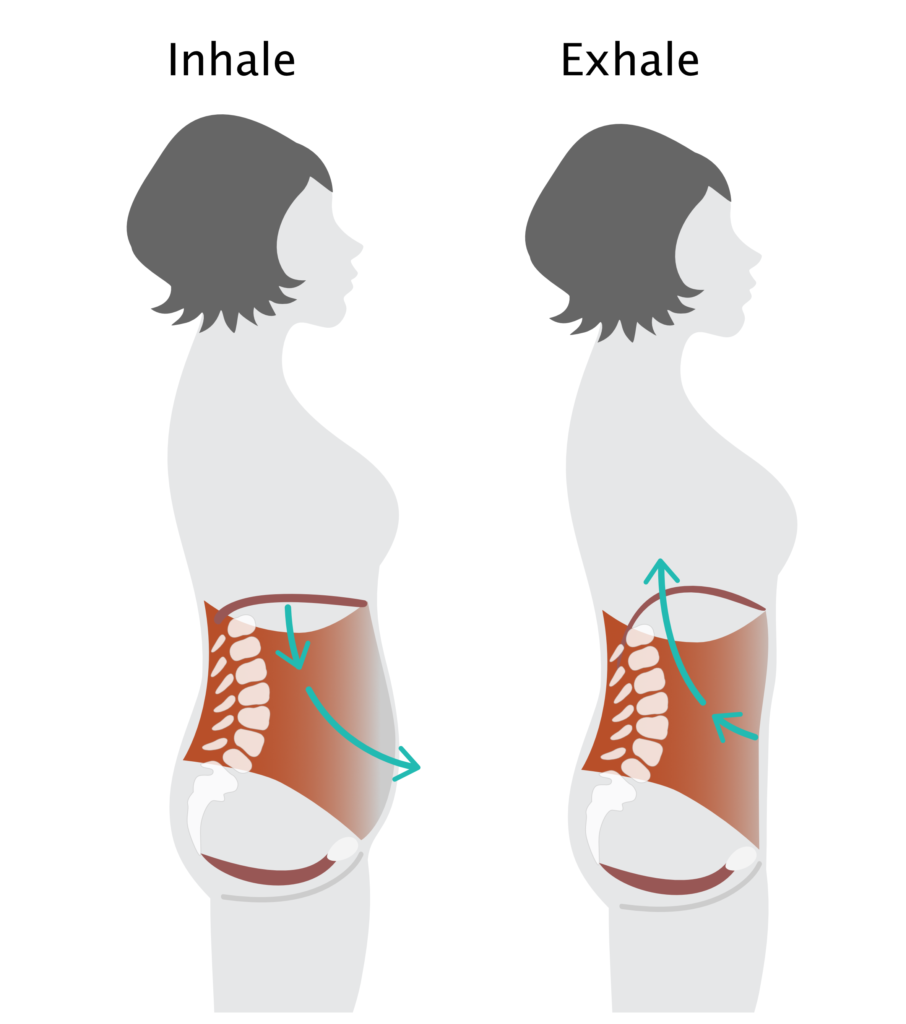

Your diaphragm and your abdominal muscles (particularly transverse abdominis) can work together or oppose each other depending on what role they play. When you simply breathe in and out, they work together – on the inhale, your diaphragm moves down, and your abdomen expands; on the exhale, your diaphragm moves upward, and your abdomen pulls in. This is its respiratory function. It is important for your diaphragm to maintain tonicity so that it can properly contract and move down and then return to its resting shape with ease. This ensures proper lung inflation and ongoing visceral massage. Different factors can affect the diaphragm’s ability to contract. Shallow breathing, exaggerated movement of the upper body during inhalation, slumped posture, stiff military posture, chronic stress –– all these factors can stiffen your diaphragm and impact its range of motion.

Your diaphragm and your abdominal muscles (particularly transverse abdominis) can work together or oppose each other depending on what role they play. When you simply breathe in and out, they work together – on the inhale, your diaphragm moves down, and your abdomen expands; on the exhale, your diaphragm moves upward, and your abdomen pulls in. This is its respiratory function. It is important for your diaphragm to maintain tonicity so that it can properly contract and move down and then return to its resting shape with ease. This ensures proper lung inflation and ongoing visceral massage. Different factors can affect the diaphragm’s ability to contract. Shallow breathing, exaggerated movement of the upper body during inhalation, slumped posture, stiff military posture, chronic stress –– all these factors can stiffen your diaphragm and impact its range of motion.

Another important function of your diaphragm is spinal stabilization. If you keep your abdomen engaged when you inhale, it will prevent your belly from expanding. The downward movement of the diaphragm will work in opposition to your abdomen, and together, they will increase intra-abdominal pressure. We do not want to have increased intra-abdominal pressure on a regular basis, but it plays a very important role in spinal stabilization during movement. Research shows that “the diaphragm assists in the mechanical stabilization of the spine via increased intra-abdominal pressure in conjunction with contraction of the abdominal and pelvic floor muscles.” (4)

Another important function of your diaphragm is spinal stabilization. If you keep your abdomen engaged when you inhale, it will prevent your belly from expanding. The downward movement of the diaphragm will work in opposition to your abdomen, and together, they will increase intra-abdominal pressure. We do not want to have increased intra-abdominal pressure on a regular basis, but it plays a very important role in spinal stabilization during movement. Research shows that “the diaphragm assists in the mechanical stabilization of the spine via increased intra-abdominal pressure in conjunction with contraction of the abdominal and pelvic floor muscles.” (4)

Here is a quick summary of how it works: “The stabilizing function of the diaphragm has been studied by several authors who have demonstrated that diaphragmatic activity can assist with mechanical stabilization of the trunk along with concurrent maintenance of ventilation. The diaphragm contributes to postural control during trunk stabilization and voluntary limb movement. The diaphragm and abdominal muscles together create a hydraulic effect in the abdominal cavity, which assists spinal stabilization by stiffening the lumbar spine through increased intra-abdominal pressure. Therefore, poor coordination of the diaphragm and abdominal muscles may result in compromised stability and dysfunction of the lumbar spine. […] Proper stabilization is critical for all dynamic activities ranging from simple, functional tasks to skilled athletic maneuvers.” (5)

Proper spinal stabilization is essential for many yoga postures. Let’s examine how it works in Virabhadrasana 1.

This is why the action of progressive abdominal contraction (“zip-up”) combined with pelvic floor lift and diaphragmatic breathing is so important in most yoga postures. It helps regulate the position of the pelvis AND increase intra-abdominal pressure to aid with spinal stabilization while we move into the pose, hold the pose, and particularly if we move our arms while holding the pose.

That is why we need to include the following elements in our yoga practice:

- Building awareness of diaphragmatic movement. Most of us cannot feel our diaphragms directly, but we can experience its movement indirectly by the outward flaring action of the bottom part of the ribcage when the diaphragm flattens on the inhale. We can also visualize the diaphragm lifting and returning to its dome shape on the exhale.

- Practicing progressive abdominal contraction (“zip up” action) with pelvic floor lift in most postures for spinal stabilization,

- Developing tonicity of the pelvic floor so that it’s not too tight or too droopy and is able to withstand the changes of pressure in the abdominal cavity and support our organs,

- Increasing the range of motion of the diaphragm by gradually lengthening all four parts of the breath (inhale, hold after inhale, exhale, and hold after exhale),

- Encouraging good posture, as both slouching and military posture affect the range of movement of the diaphragm,

- Discouraging rigid holding of the abdomen in daily life as it creates unnecessary intra-abdominal pressure. For most of us, our bodies will create that support when necessary on their own. It’s more important for us to increase that support consciously during exercise, yoga, heavy lifting, and other more physically demanding activities.

Let’s put all these ideas into action – next we will feature a yoga practice that helps you become more aware of your diaphragm.

Try this yoga practice if you want to increase the muscle tone of your diaphragm

References

- Anatomy of Breathing by Blandine Calais-Germain

- Fundamentals of Anatomy and Physiology (7th edition) by Frederic H. Martini

- Restoring Prana by Robin Rothenberg

- Changes in intra-abdominal pressure during postural and respiratory activation of the human diaphragm by Paul W. Hodges and Simon C. Gandevia

- Stabilizing function of the diaphragm: dynamic MRI and synchronized spirometric assessment by P. Kolar et al.

Fantastic and insightful article Olga, you are a wonderful resource, thank you for your continued research and making it relevant to how we practice

Thanks once again Olga for sharing all your knowledge in clear language, always backed with a lot of references and taken forward with a practice. Pranams to you and look forward to the practice next week. Already delving into Robin Rothenberg’s book on pranayama.

Freakiiing amaziiing as always!!! I wish you were my biology & physiology teacher in primary and middle school! Well, at least now I have you as my fav teacher and I soak all your articles like honey! Thank you Olga! The fact about how heart moves up and down with breath is so POETIC and amazing fact.

I can’t Thank you enough for all your articles. I have been reading them all since one of my yoga teachers recommended your website

So happy to see the involvement of the pelvic floor and how important breath is to the tone and elasticity