Why do we tend to expect the worst when it comes to pain? Negativity bias

If you accomplish ten great things today and make one mistake, what will you more likely think about when you lie in bed at night? Most likely, you will think about that one mistake, even though the positive accomplishments far outnumber it. This is an example of negativity bias and it is an intrinsic evolutionary quality of our brains. What does it mean, and what does it have to do with chronic pain? Let’s explore.

For our ancestors, serious mistakes were costly. If they had mistaken a stick for a snake and got scared in vain, it wouldn’t have lasting consequences. But if they had mistaken a snake for a stick, it would threaten their survival. The brain evolved to err on the side of safety and has come to expect snakes even in places where there aren’t any. From the perspective of survival, it is better to be overly cautious than not cautious enough. That is why our brains are wired to expect the worst.

Now imagine that your ancestor did once mistake a snake for a stick, got himself in a perilous situation, and somehow got away. You bet his brain would mark that experience as extremely dangerous, file it away in a “High Alert” folder, and become even more vigilant by developing a quick-response neuropathway for recognizing and dealing with similar situations. In response to any experience that threatens our survival or has the potential to compromise the integrity of the body, the brain learns how to react quickly and becomes overly sensitive to any similar threats.

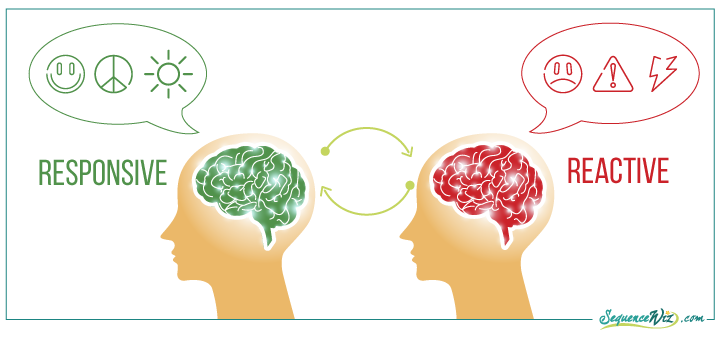

In addition, because of negativity bias, the brain is constantly scanning the body and the environment for signs of potential trouble. Even when you are relaxed and at ease, this process still takes place behind the scenes in order to react quickly at the slightest sign of danger. When the signs of trouble are detected, the brain quickly switches from its responsive mode into the reactive mode, which means swift sympathetic activation (“fight-or-flight”), dumping of cortisol and other stress hormones into the system, and immune response to fight potential infection.

(This terminology (responsive-reactive, as well as green brain-red brain) is used in Hardwiring Happiness by Rick Hanson, Ph.D. You can read much more about the qualities of those states in this book.)

To summarize, negativity bias makes us

- Switch to reactive brain mode fast when a threat is detected

- Stay vigilant for signs of potential trouble even when we are at rest

- Create a super fast highway to the reactive state from repeat bad experiences

- Become hesitant about returning to the responsive mode even when the danger passes.

Any acute pain episode is perceived by the brain as a threat, which quickly puts it into the reactive mode. As a result, the brain will constantly scan the body for similar pain signals (and might mistake other sensations for pain), will mount a swift response once a pain signal is detected, and will linger in the reactive, sensitive state instead of returning to the calm, responsive mode. This is what gives rise to chronic pain.

Other factors might make the experience of pain more or less pronounced, help it come to an end faster, or prolong it. Let’s take a look at how the brain can interpret other signals as pain.

References

Hardwiring Happiness: The New Brain Science of Contentment, Calm, and Confidence by Rick Hanson, Ph.D.

Good Morning! Your title makes me almost angry! How do you portend to know what “we” always expect when it comes to pain? yellow journalism works– yes. Using this kind of tactic however discredits the author and confuses readers. Many people do not expect the worst when it comes to pain. Bumps, scrapes, bruises happen. Many stop hurting in a few moments or minutes.

Hi Cathy! Wow, that is a strong reaction to the title. The “we” in the title applies to “humans” since the entire article is about negativity bias which is an evolutionary trait of our brains. If your experience of perceiving pain is different, this is your accomplishment – it means that you discovered how to turn off your sympathetic response when it reacts to trigger. Like I said at the end of the article, there are many factors that can affect our reaction to pain, on top of this inherent biological response. This will be the topic of discussion next time. Thanks for sharing.

The reader’s comment is a good example of the responsive vs reactive brain at work. I catch myself doing that at times. In reality, nothing makes me react other than myself. It’s what we humans do, for sure, and it’s powerful to see it happening. I was interested in learning why our brains developed the ability to focus on the one negative and overlook the many positives – survival was at stake, originally.

Excellent points Marie, thank you!

Thank you for addressing the issue of chronic pain. I’m a 68-year-old who has dealt with peripheral neuropathy for many years now. While the physical aspect of yoga has been of great benefit … stretching muscle cramped by nerve damage, for example … gaining ascendancy over the body/mind tendency toward reactivity is crucial, and I’m always eager to learn more. I look forward to reading your next entry on this topic.

Very interesting series, thanks!

Cathy has a point. “Always” is a strong word. I believe we learn, in many circumstances, to distinguish between the pain that comes from real, serious danger and the minor bumps and bruises that can safely be ignored, especially when we have more important things to deal with. This ability would seem to be an important survival skill, too.