How does pain become chronic?

A former client of mine, let’s call him John, bent over to tie his shoes one day and was unable to sit up because of excruciating pain in his lower back. He was taken to the hospital and put on heavy-duty muscle relaxants. Was it the action of tying his shoes that caused his back pain? Most certainly not. But it was the proverbial straw that had broken the camel’s back. Very often, the pain in the body shows up as a result of ongoing physical stress rather than one single injury (like a slip or a car accident).

There is a reason we get pain – it alerts us to the dangers in our environment and protects the integrity of our bodies. It teaches us not to touch hot things and stay away from sharp teeth and claws. The neck pain we get from staring at the computer all day has the same purpose – to remind us to use our bodies wisely and take breaks from repetitive actions. It’s the way our bodies communicate the message: “I am trying to keep myself safe and whole, and this action might hurt me.” Quite often, we choose to disregard this message because it’s inconvenient and put up with milder instances of pain until the body rebels and says, “That’s enough! I warned you,” and goes into a full-blown spasm. My client, John from earlier, had episodes of mild lower back discomfort for years, but he just brushed those off and didn’t do anything about them. That “shoe-tying” spasm got his full attention. And even though some people get caught off guard and wonder – Where did this come from? Everything was fine until now! – often, episodes like that point to consistent neglect of the body’s more mild pain signals.

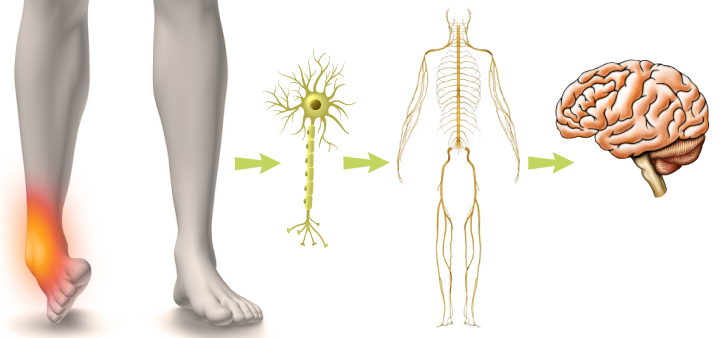

The recurring pain that lasts longer than six months is usually referred to as “chronic pain,” and it differs quite a bit from an acute pain episode. Here is how acute pain is supposed to work (whether you twist your ankle or put your hand on a hot stove.

Body is threatened in some way

Protective response is initiated by the central nervous system (the neuromatrix of pain)

Healing process begins

Central nervous system recognizes that the threat had passed and healing is underway

Pain goes away, healing is complete

Brain learns how to handle similar threats

This is supposed to be the end of the story, but sometimes it isn’t. “Most chronic pain has its root in physical injury or illness, but it is sustained by how that initial trauma changes not just the body, but also the mind-body relationship.”(1)

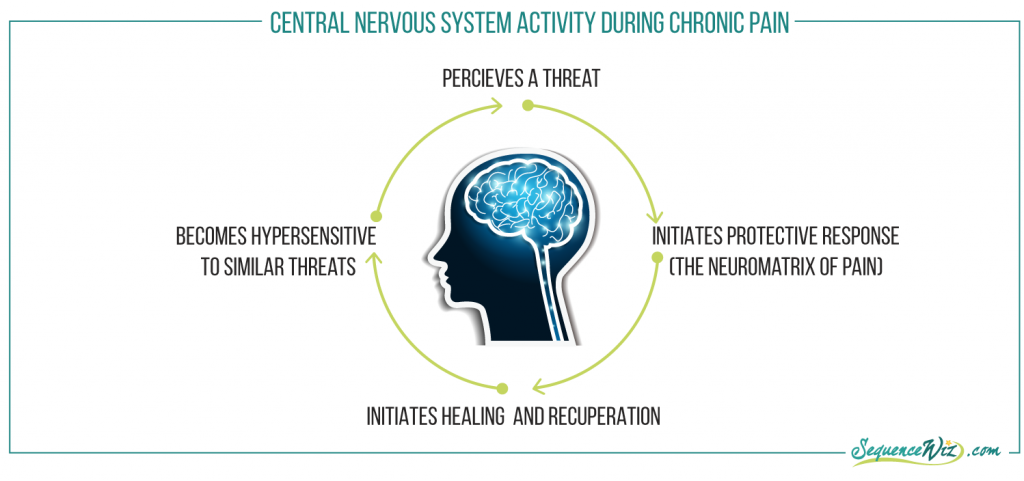

Instead of this acute pain experience coming to an end, the body and brain perceive an ongoing (instead of a one-time) threat and continue to send pain signals, getting stuck in the vicious cycle.

“The assumption is, if you have chronic pain, you must have a chronic threat in the body that continues to alert your brain. And if your pain gets worse, it must be because the threat in the body has gotten worse. With chronic pain, this is rarely the case”(1).

This perceived on-going threat can be real or not real.

It is real if you continue with the habitual movement patterns that got you hurt in the first place and keep reinjuring the troubled area. It is similar to a basketball player who blows his knee out and keeps playing. How is the injury supposed to heal if he keeps running and jumping? And even if you are not involved in high-impact sports, the way you use your body on a regular basis (how much you sit, how far you drive, your body positioning, and so on) can keep irritating the same vulnerable areas.

Or the brain and body can interpret other signals as pain (whether they are real or not) and have a disproportionate response to it. It is usually a result of your body and nervous system learning from the previous painful experience and commonly shows up in one of three ways (summarized by Kelly McGonigal, Ph.D. in her book Yoga for Pain Relief):

Pain sensitization: Nerve endings can become so sensitive to pain that they interpret any sensation, even pressure or inflammation, as pain.

Neuroplasticity: The central nervous system learns to interpret situations and sensations as threatening and mounts a fast and powerful pain response (which might be way bigger than the perceived threat).

Blurred boundaries: Over time, the boundaries between actual physical sensations, fears about them, and stress associated with them become so blurred that either one can be interpreted as pain by the brain and facilitate a full-blown pain response.

An acute pain episode can lead to chronic pain, or chronic, low-grade pain can develop into an acute episode. But whichever way it happens, the process alters the way the body and brain perceive and react to pain triggers.

Any acute pain episode is perceived by the brain as a threat, which quickly puts it into the reactive mode. As a result, the brain will constantly scan the body for similar pain signals.

References

- Yoga for Pain Relief by Kelly McGonigal, Ph.D. – This book is a great introductory resource that describes the nature of chronic pain and how yoga can help with it.

A great article- thank you. I would appreciate your discussing other specific situations – like arthritis in this context. Having always been active- running, yoga, Pilates – now facing chronic pain and joint replacement in hips and knees at age 69. Too late for me but it would be great if you could give tips to young people on what to do after injuries from running or other exercise related injuries before they turn into chronic pain or arthritis later in life.

Thank you for your comment Ingrid! We will get into some strategies for chronic pain management soon – hopefully they will also be helpful as preventative measures!

Hi Olga,

Having lived through the scenario you described, and being named Jon! I wonder what you think of the work of Dr. John Sarno. I have recently become aware of his theory and have found it helpful.

Hi Jon! I am not familiar with the work of Dr. John Sarno. How would you describe it?

Well, it would probably be best to search out one of his books or watch some of the interviews with him on You Tube. But basically, he says that about 95% of chronic low back, shoulder and neck pain is not due to any structural problem but rather an effect of suppressed emotions, especially anger. I know, it seems a bit out there, but is it? A significant component of this is lack of oxygen, which causes muscles to spasm. How many times have would told students to “breathe into” a particular area of the body? There is a lot of what he says that makes sense. My at doctor here in Portland,(remember PDX!) actually told me about Sarno. Surprising, in a good way!

Jon, thought I’d add a note on this. I would add hip pain to the mix as that is what reading Dr. Sarno’s “Healing Back Pain” book helped in my case. I heard about the book at a Gary Kraftsow workshop in Austin then again at a later workshop with Leslie Kaminoff. In both cases there were people in the room who felt his theory had helped them. I agree with you that it seems “out there” & was very doubtful except…… after years of hip pain, it rarely hurts anymore. Glad to know of someone else who has been helped by this.