When you are hurt where does the pain come from?

A few years ago, my family moved from one house to another. On the moving day I was carrying a big heavy box down the stairs and missed the last step. Both me and the box came crashing down as my ankle twisted under me. It was rather painful. Let’s try to explain my experience of pain using a couple of popular pain models.

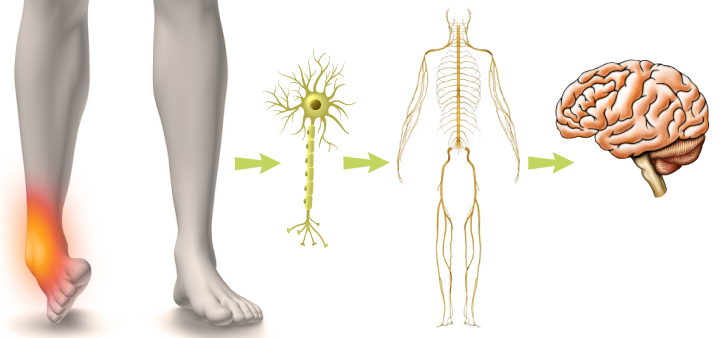

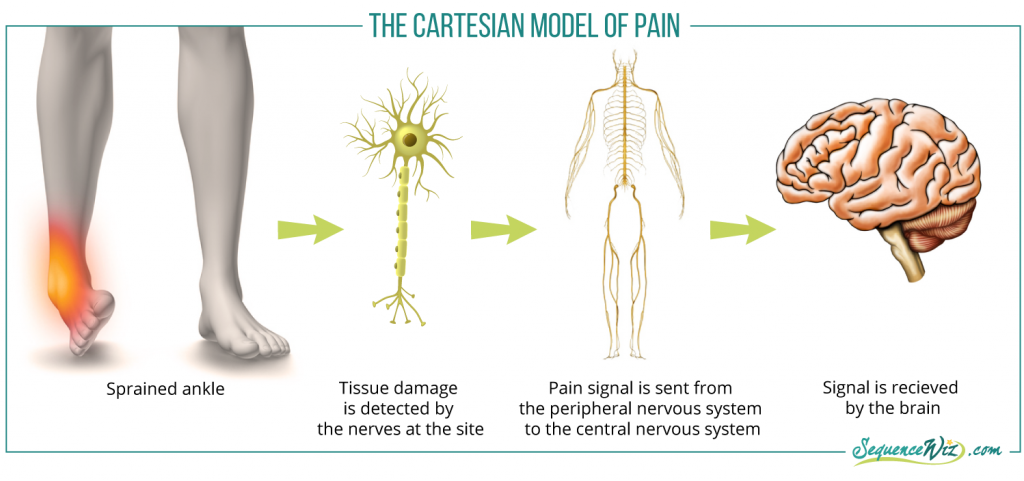

The Cartesian Model of pain

This model was developed by the philosopher Rene Descartes and has been a prevalent explanation for the pain experience for many decades. It postulates that the pain is produced because tissue gets damaged, and the signal of that damage gets sent to the brain via the peripheral nervous system and then the central nervous system. In my case, it would look like this:

In this scenario, the central nervous system (the brain and spinal cord) is the passive recipient of the signal from the damaged tissues in the ankle. The pain signal will subside when the tissue is repaired. In this model, the generator of pain are the structures of the ankle. This seems reasonable, and this model is still used widely today whenever we try to identify the source of our own or someone else’s pain.

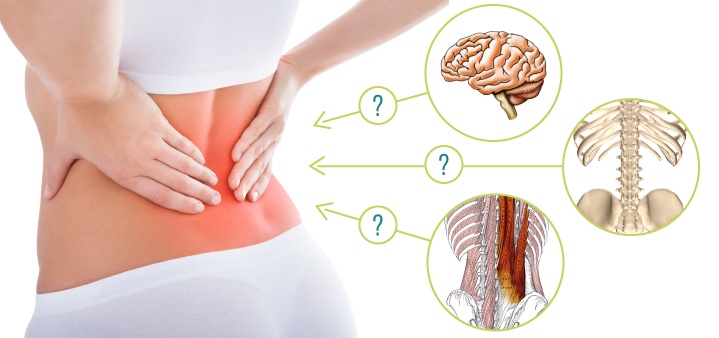

However, in the 1980s and 90s, psychologist Ronald Melzack conducted studies on people who experienced phantom limb pain (when the limb is surgically removed, but the patient continues to feel pain in the non-existent limb). This led him to question whether the generator of pain was the actual part of the body where the damage had occurred or whether pain was generated in some other place entirely. This question comes up for doctors all the time when they have trouble matching the structural damage that they observe on the MRI, for example, with the patient’s actual experience of pain. A person with severe disk damage might not experience any pain, and a person with no discernible structural damage might be in agony. Examples like this led Melzack to form a different model to describe the pain experience that he called the “neuromatrix of pain.”

The Neuromatrix of pain

The notion of the neuromatrix describes the experience of pain as a result of different parts of the brain working together. The neuromatrix includes the spinal cord and various parts of the brain that generate sensory, emotional, cognitive, motor, behavioral, and conscious responses. So in this model the generator of pain is the central nervous system. Here is what it looks like (simplified):

Let’s analyze my pain experience using this model. My response to my ankle injury was:

- “Man, that hurts. Feels like I twisted my ankle” (sensory)

- “Perfect timing. I am in the middle of the move. I still have so much stuff to do” (emotional – annoyance)

- “Can I get through this move? Do I have anything else going on tonight that would be impeded by my twisted ankle? Will this cause lasting damage?“ (conflict assessment)

- “I need to get through this move and then I can rest” (motivational)

- At the same time, my sympathetic system was revved up making me more alert and mobilizing my energy.

While gathering all this information about different aspects of the injury, the brain needs to decide how worried it should be about this incident. Recent studies also show that the intensity and duration of pain response will depend on how much attention you pay to it, your emotional state, the social context, your prior learning about pain and other factors.

In my case, the response to the assessment was the following:

“My family is relying on me to complete this move (social context). I don’t have anything else going on later; I just need to power through this, and then I can tape it and rest it (setting the course of action). It’s no big deal – I twisted my ankle many years ago, and it was fine after a week (recalling prior experience). Nobody ever died from a twisted ankle (calming existential fears).”

This response sends the signal to the autonomic nervous system that manages stress response that the injury is minor and manageable; it invites it to dull the pain for now and begin the healing process later.

As a result, I was able to continue with moving boxes while limping. Just as I expected, the pain got worse afterward but was gone in about a week. Followed by some ankle strengthening it hasn’t happened again and my ankle is completely fine now. The experience taught me to always look where I am going, especially on the steps.

Now imagine what would happen if I was a ballerina who had a performance scheduled later that night. The emotional response would have been much stronger. For example: “OMG, what am I going to do about the performance tonight?! My creative director is going to be so mad! Can I find a replacement on time? Will this compromise my position in the dance company? What if this ends my career?!” And things can snowball from there, leading to a more dramatic pain experience and a much more pronounced stress response.

Recall your past experience dealing with some sort of injury – does this model of pain make sense to you? Did you notice that your response to injury affected the intensity of pain?

The recurring pain that lasts longer than six months is usually referred to as “chronic pain” and it differs quite a bit from an acute pain episode.

References

- Yoga for Pain Relief by Kelly McGonigal, Ph.D.

- Neuromatrix of Pain by Institute for Chronic pain

- Autonomic, Endocrine, and Immune Interactions in Acute and Chronic Pain by Wilfrid Janig and Jon D. Levine (Textbook of Pain)

- Central Nervous System Mechanisms of Pain Modulation by Mary M. Heinricher and Howard L. Fields (Textbook of Pain)

wow this is really interresting, thanks!!!