How to train your balance

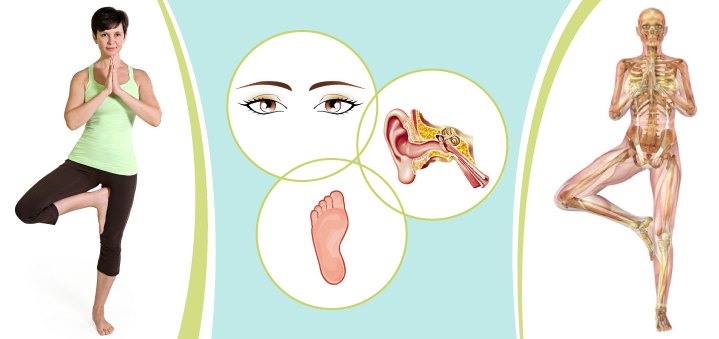

Watching your kid learn how to walk is a pretty fascinating experience. When you see him wobble and plop down with almost every step, it’s hard to believe that one day he will be running, riding a bike, playing soccer, and so on. However, over time, through practice and repetition, his balance gradually starts to improve through the process called “facilitation.” It means that nerve impulses sent from the sensory receptors in the body to the brain stem and then back out to the muscles begin to form a new pathway, and the more often the child engages in this activity, the stronger that pathway becomes. Before long, it is a well-established “highway”, which means that the body and the brain know exactly how to handle the process of balancing, and the child is now able to maintain balance during any activity.

“Strong evidence exists suggesting that such synaptic reorganization occurs throughout a person’s lifetime of adjusting to changing environments or health conditions”(1). This means that our bodies and brains adapt to the changing external or internal conditions, learning how to deal with them more efficiently. This is why athletes practice the same move over and over again so that, however complex, it becomes almost automatic. This is why we need to train our ability to balance so that we build neural pathways that enable the brain and body to know exactly how to handle maintaining balance throughout various activities and how to recover balance if it suddenly becomes challenged (like if you slip on ice).

The bottom line is that there is no other way to train your balance other than to practice balancing. We need to do it more to get better at it; that’s all. Yoga is unique in a way that it gives us an opportunity to train our balance by challenging it in a variety of ways.

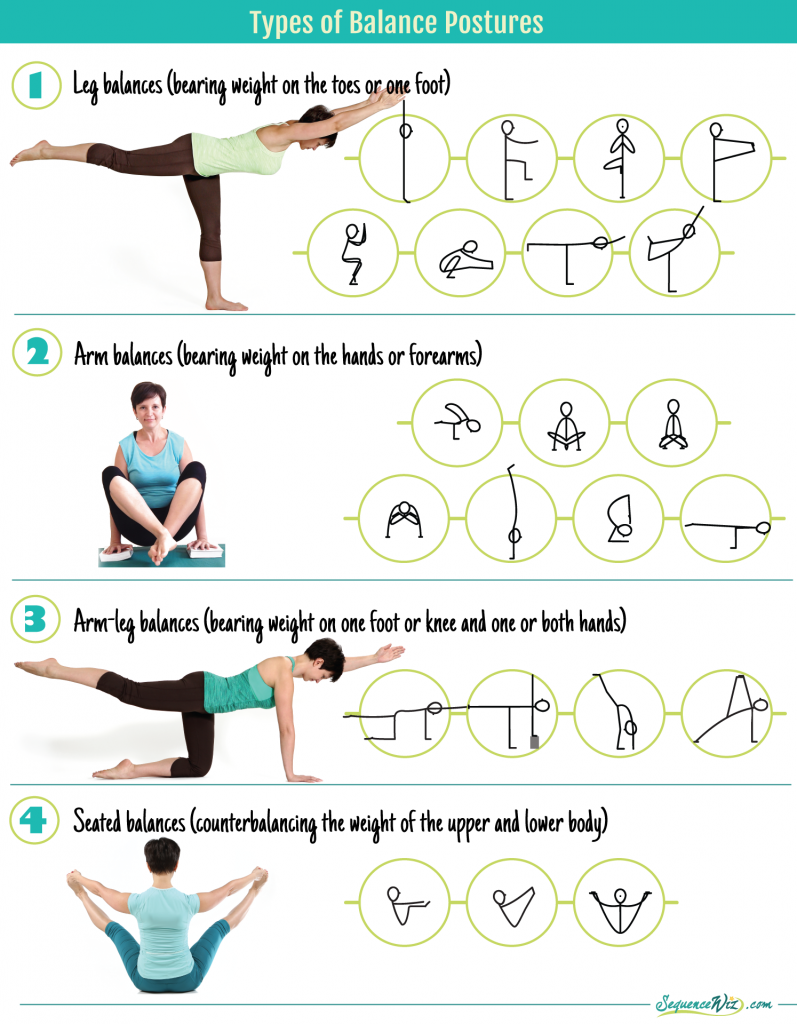

“The key to accomplishing balance postures is the ability to achieve equilibrium on the unstable base, using the displaced body weight as a counterbalance,” says Gary Kraftsow. In yoga, we can use feet, toes, hands, forearms, buttocks, and even head to form that base, which means that the counterbalancing will be happening between very different parts of the body and accomplish different things. Here is how we can classify the balancing poses in yoga.

Leg Balances are practiced while standing on the toes or on one foot. There is no question that to be fully functional human beings we need to be able to carry and support our own weight in the upright position. Leg balances help us refine the way we hold and move body weight; they are the most useful poses for strengthening and stabilizing the body for our daily tasks.

Arm Balances are practiced while standing on the hands, or forearms and hands. They emphasize strengthening the muscles of the arms and shoulders, as well as the lower back, abdomen, and pelvis. If you have weakness or injuries in the wrist, elbow, or shoulder joints, be very careful with those postures or skip them altogether.

Arm-leg balances distribute the weight between one leg and one or both arms. Poses like this are useful for strengthening the core and integrating the upper and lower body. Some poses in this category are cross-lateral movements. We do those all the time in our everyday activities (walking, climbing stairs, riding a bike). Movements like that are supposed to activate both brain hemispheres in a balanced way and heighten cognitive function.

Seated balances require counterbalancing the weight of the upper and lower body, which requires strong core engagement, as well as hip and leg strength. Those poses are easily adaptable to students of any level of physical conditioning.

In addition to challenging your balance, all of the poses above have some other element in them – some are backbends, some are forward bends, and so on. This means that when we design a practice that includes balancing poses, we need to take into consideration and prepare not only for the balancing element itself but also for those secondary pose attributes as well.

One major category that is not included here is Inversions. These are poses that are practiced upside down. These poses challenge your balance in a completely different way and have many benefits; and they carry many risks, as well. This category deserves its own discussion, and it is up to the teacher to decide whether or not those poses are appropriate for her students and should be included in the practice.

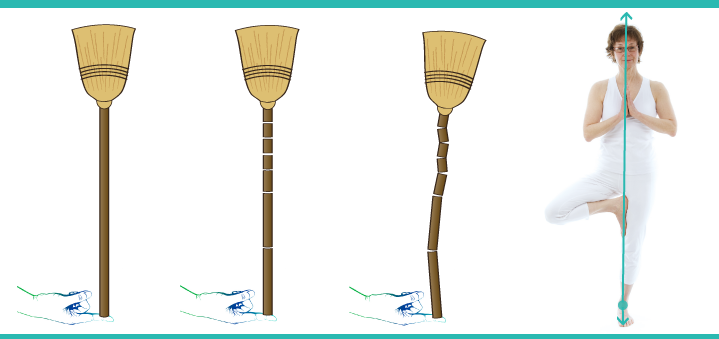

When it comes to balancing yoga poses, more often than not, we practice them as static postures, holding them for some period of time. This certainly has great value in teaching your body how to maintain stability on an unstable base. However, another very important aspect that is often overlooked is that we also need to train the body to regain balance after it has been compromised (by missing a step, slipping on the ice, tripping over a toy, etc.)

Let’s discuss the differentiation between static and dynamic balance and how it educates our approach to yoga practice design.