Four steps to minimize the stress placed on the intervertebral disks

Did you know that astronauts get taller in space? According to NASA studies, when the spine is not exposed to the pull of Earth’s gravity, the intervertebral disks expand, and as a result, the spine gets a bit longer. That small gain is short-lived, however. Once the astronauts return to Earth, their height returns to normal after a few months of adapting to the Earth’s gravitational pull. (1)

In fact, you can test the effect of gravitational pull yourself if you measure your height before you go to bed and then again right after you wake up. The difference can be as much as two centimeters, which is attributed to the fact that intervertebral disks get compressed and dehydrated during the day (because of the gravitational pull and mechanical forces from both movement and sitting). During the night’s sleep, the disks get rehydrated again – as a result, you wake up taller.

A similar mechanism is believed to be responsible for the loss of height with age. Apparently, as we age, the composition of our discs changes (they become more fibrous), and they become progressively more and more dehydrated. “A less hydrated, more fibrous nucleus pulposus [the inner core of the vertebral disc] is unable to evenly distribute compressive forces between the vertebral bodies. The forces are instead transferred non-uniformly to the surrounding annulus fibrosus [outer protective layer]”(2), which can lead to progressive structural deterioration, disk herniation, and pain.

It is pretty obvious that we want to keep our intervertebral disks hydrated and our spines aligned to minimize the stress that is being placed on the disks. How do we go about it?

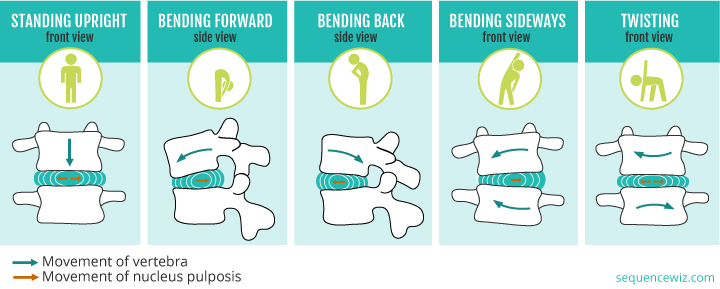

Step 1: Move more. No surprise here. Some mechanical stimulation of the disks is necessary to “induce nutrient diffusion and to promote matrix synthesis”(2), which means that we need to move the spine forward and back, side to side, and twist to keep the disks nourished. A well-balanced yoga practice will usually take you through the full range of spinal motion.

Step 2: Sit less. When it comes to spinal disks, “excessive loading can result in localized tissue injury that is slow to repair and alters strain distribution throughout the extracellular matrix of the entire disc” (2). This means that we need to minimize excessive loading on the disks, especially in positions that alter the natural curves of the spine. One of the most common ways we load our disks is by sitting a lot.

“The weight is distributed in a standing position,” says Kelly McGonigal, Ph.D., a health psychologist at Stanford University and a leading expert in neck and back pain. “But when you sit, you distort the natural curve of the spine, which means your back muscles have to do something to hold your back in shape because you’re no longer using the natural curves of the spine to lift yourself up against gravity.”(3) Alignment of the spine changes in the sitting position, which means that the compressive forces on the lumbar discs change as well, which dehydrates them more rapidly and can create structural problems down the line. Short stretch and movement breaks in the course of the workday are very effective in minimizing the compressive load on the spine.

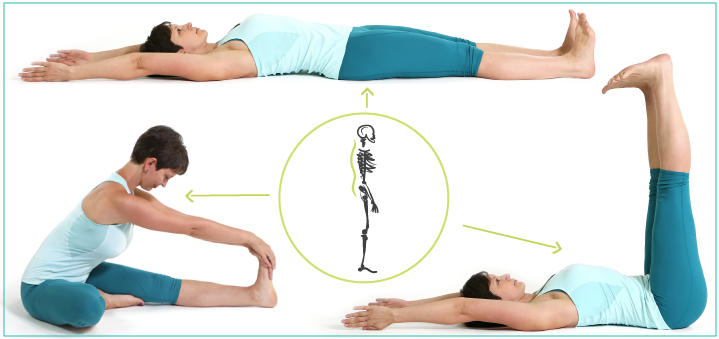

Step 3: Change the body’s position in relation to gravity (from time to time). Disks rehydrate more easily when we change the body’s position in relation to gravity. For example, the horizontal position works better than the vertical, both because the angle of gravitational pull changes and because the deep muscles that normally work hard to keep the spine upright can relax.

Yoga practice is unique in that throughout the practice, we dramatically change the body’s position relative to the ground. We do some poses in the upright position, some in prone (on the stomach), some in supine (on the back), we bend sideways and even stand on our heads. Altering the body position changes the load on the vertebral disks AND shifts the blood distribution within the lungs, which facilitates better blood-oxygen exchange. To maximize this effect you need to breathe deep and stay in the position for some time.

Step 4: Build strength and elasticity in the deep and superficial musculature around the spine to provide sufficient support without creating stress and tension.

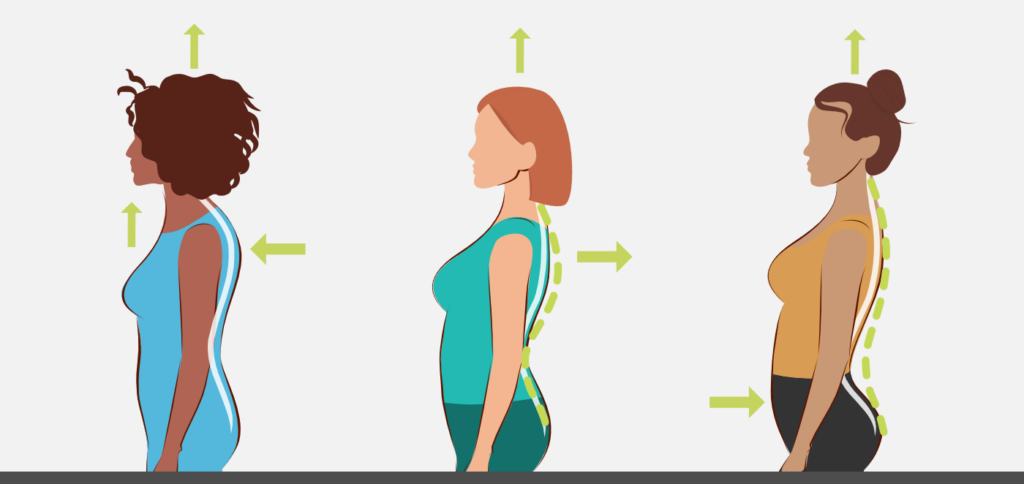

Many yoga poses are useful in strengthening the postural muscles, but axial extension postures are particularly good for that. The axial extension means that the main purpose of each pose in this category is to lengthen the spine along its axis while integrating the spinal curves and building a better relationship between them. While the movement of lengthening the spine might seem small, those types of poses are very effective in building strength and elasticity in deep and superficial musculature around the spine and strengthening the core musculature. When done correctly, those poses also help us improve the postural alignment and integration between the spinal curves. When postural muscles are strong and supple, they reduce the load on the entire body and help it function better mechanically and physiologically.

There are four distinctive groups of axial extension poses; they have many similarities and also many differences. Why and how do we practice them?

Quoted Resources

1. My How You’ve Grown! (NASA website)

2. Degeneration and regeneration of the intervertebral disc: lessons from development (PubMed Central)

I love this post. I have a personal goal of becoming 1 mm taller each day and I can’t wait for the axial extension poses! thanks