Should we engage the abdomen all the time?

Let me ask you a question: if a bowl of ice cream tastes good, would a bucket be even better? Whenever one of my yoga clients encounters a yoga pose that challenges her yet feels rewarding to conquer, she says: “That was great – let’s do it every time!” I think you know where I am going with this – if something feels good and/or appears to be useful, we tend to crank it up in hopes that the more we do it, the more benefit we will get. This applies to the abdominal engagement as well. We might read about the benefits of the core engagement, then find it useful in our yoga practice, and the next thing we know, we keep pulling our stomachs in everywhere we go in hopes of maximizing the benefit. Just like with the ice cream example, it doesn’t work that way. Here is why.

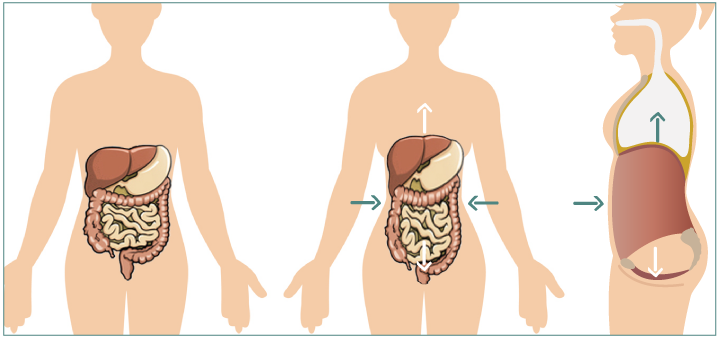

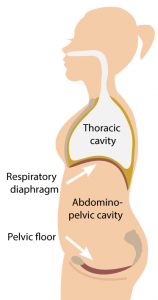

If your abdomen is a container, then it needs to have a top and a bottom to contain and protect its contents. In your body, the bottom of the container is formed by the pelvic floor muscles, and the lid is the diaphragm. Your abdominal cavity is packed pretty tight with organs, especially the digestive system, and even though each organ has its designated location, they can also slide around when the contents of your abdominal cavity get squeezed.

You know how when you cough or laugh hard you might feel like you peed a little? (And if you are pregnant, you probably did 🙂 ) This is because, during coughing, your abdominal muscles contract, increasing intra-abdominal pressure, which means that your internal organs get squished a bit more and push up against your diaphragm and down against your pelvic floor (and the organs located there, such as the bladder). A similar increase in intra-abdominal pressure happens every time you contract your abdomen at will.

If you decide to keep your abdomen engaged all the time, you will be continuously pressing your organs against the diaphragm (which will limit its range of movement) and the pelvic floor (which might weaken it). You know how you can eat so much at a Thanksgiving dinner that it makes it hard to breathe? This happens because the content of your digestive system expands and limits the downward movement of the diaphragm on the inhale; as a result, you might get shortness of breath. If you do it often enough, it will get harder and harder to take deep breaths because the diaphragm (being a muscle) will not move down as willingly. Studies show that increases in intra-abdominal pressure can affect both your breathing and your cardiovascular health. Now, I am not saying that practicing abdominal corset all the time will cause heart problems – that is going way too far. But keeping the intra abdominal pressure high all the time will affect your breathing.

Continuous pressure on the pelvic floor is not advisable either. The pelvic floor acts like a hammock that supports your abdominal contents, and if it gets “droopy,” it can lead to organ prolapse, urinary and bowel leakage, issues with sexual function, and so on. Some of the reasons that lead to “droopy hammock” are pregnancy and childbirth, obesity, heavy lifting, high-impact exercise, and chronic coughing – as you can see, all of those activities involve an increase in intra-abdominal pressure. That is why, for example, it is usually recommended that you engage your pelvic floor muscles when you cough. That is also why many yoga teachers suggest that you engage your pelvic floor muscles simultaneously with progressive abdominal contraction during your yoga practice. This is generally a good idea, except we can run into a couple of issues here:

- Most people need to be taught how to engage the pelvic floor muscles properly; otherwise, they might tense their buttocks, anus, or legs, which doesn’t help with support.

- Both contracting AND release are important, since we want to build the muscle tone without creating tension. It works best if you contract those muscles during exhalation, then maintain the contraction for few seconds as you hold the breath out and then gradually release the contraction as you inhale. This is best done in a seated position or in other simpler poses with complete focus on what you are doing, otherwise it will drown in the sea of other anatomical cues.

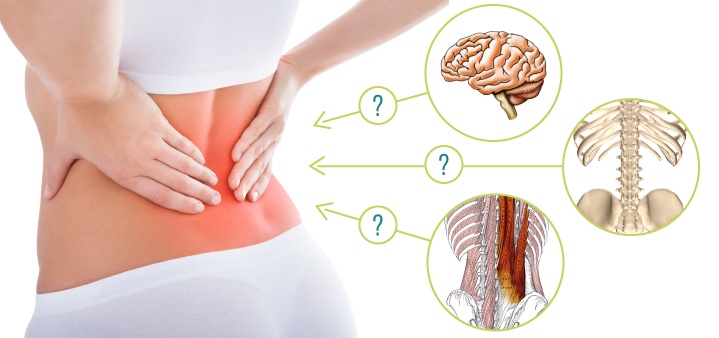

So when should we engage the abdomen in our daily lives? It is most useful when we do physical activities that load our spines, whether it’s exercising, lifting, throwing, rowing, and so on. Research shows that intra-abdominal pressure “has a substantial spinal unloading effect for all directions of generated external moments” (including bending forward, back, sideways, and twisting). The paper concludes: “These findings support the idea that intra-abdominal pressurization is beneficial because it unloads the spine.”

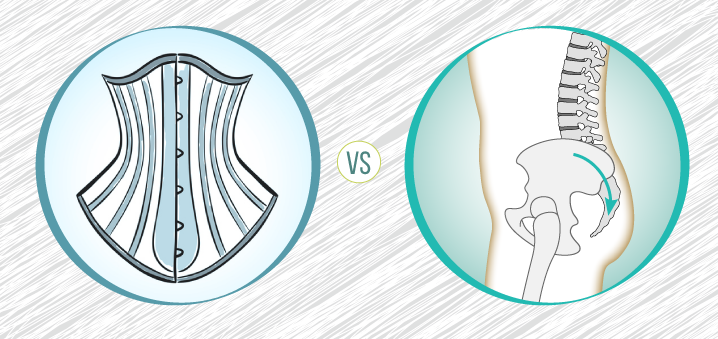

To sum up, most things are good in moderation. The abdominal contraction (“corset”) that leads to an increase in intra-abdominal pressure works well to support the spine during challenging physical activities, but it shouldn’t be prolonged, as it can affect the depth of breathing and the tone of the pelvic floor muscles.

Want to work with your core in your yoga practice? Try this yoga practice to stabilize your core and make your core muscles work together. This helps protect your lower back and take the load off your spine in all your daily tasks.

I think confusion is common between pelvic floor muscles and “corset abdominal muscles” when speaking of “core”. While it is possible to engage theses sets of muscles independently, in my experience, they tend to recruit each other. I think the best way to “engage the core” is to start with the pelvic floor muscles, recruiting and extending upwards to the abdominals to provide whatever support is needed based on the strenuousness of the activity. That way you are protecting the hammock as well as the spine.

Agreed!

I think this is a good article, though it seems a little bit confusing about when we should not be engaging the abdomen, for example indicating that ‘all good things in moderation’ but what does this mean for our asana practice? Even in our daily lives we need to lightly engage the abdomen when sitting or standing to support the lower back.

I’m curious, are there any specific poses where you would want to relax the abdomen and pelvic floor?

It seems with virtually all exercise you need a light contraction, and outside of asana relaxing the abdomen could be practised with ‘deep belly breathing’ so maybe the real focus should being able to relax that abdomen with these types of practices which could also be done periodically throughout the day while sitting.

Hi K, thank you for your comment! As I wrote in my previous article, in my tradition we pretty much engage the abdomen with every exhalation throughout the entire asana practice (not during pranayama or meditation unless it is a specific area of focus). It is my belief working with the “corset” during the yoga practice and exercising helps to translate that awareness of the core into the daily life and maintain a “resting muscle tone” of the core musculature. So my point is – yes, please, engage it all the time when you are loading your spine (in a yoga practice, exercise routine or any other place), but then leave it along when you are not. And it can be rather useful to engage “the corset” for the sake of practicing at different points during the day, but, again, not all the time! 🙂

Thanks for posting this article. When referring to “loading your spine” can I assume the technique is the same as practicing Uddiyana Bandhathe? … or is this a different type of practice?

Thank you for yet another informative and interesting article. This topic is something I think about a lot. You make some excellent points and I am in complete agreeance about using the corset in more challenging postures and to support the spine however, I am also interested in what ‘K’ was talking about. I have a memory, from around puberty, where my mother and I were talking about holding our tummies in. I have always been aware that many women are constantly lightly contracting their abdomenal muscles and ‘holding’ their stomachs in. Later in life, as I trained in yoga, Pilates and so on I gained a better understanding of the anatomy of the core however I am still unclear about ‘how much’ to engage at times when we are not stressing the spine or exerting ourselves (ie: when sitting, walking, hanging out the laundry, etc). I remember , in my dance school days, being told by a tutor to keep a 30% activation of the core at all times. After practicing this for some time (several years) I found myself tending toward anxiety and realised I had been chronically restricting my diaphragm and therefore not breathing deeply which, in turn, created a stress response in my nervous system. So I toned it down. But, it still feels unusual to have a completely relaxed belly, outside of meditation and breathing practices. I love the feeling of being ‘in my belly’ and letting it all hang out in all its post baby glory, but this does leave me feeling as though I am very ‘loose’ around the pelvic, lower back and hip area. It certainly helps me to ‘chill out’ and not be so uptight, which I am guessing is the parasympathetic NS coming into effect via lovely deep breathing. Anyway, I have waffled on enough! I apologise but, as you can tell from the length of my comment there are definately areas that are unclear for me, and I am guessing I am not alone, in regards to how much, for how long, and when should we turn the core ‘on’ and when should we let it be completely ‘off’.

Hi Jessica! I completely agree with you. I think of the abdominal muscles as part of the postural muscles that maintain our alignment while standing, moving etc. They are not completely relaxed when we are in the upright position because they control the degree of tilt of the pelvis. Personally I know that if I intentionally relax my abdomen completely my pelvis would tip forward and stress my lower back. So the low degree of contraction is fine. Most of us do it unconsciously and it happens naturally. We usually run into trouble if we begin to intentionally tense the abdomen in an effort to keep a flat stomach or whatever. So I would suggest that you work on your core strength while you are doing yoga or exercising and then let the body do its natural thing at other times. I know it might be hard to find the “golden middle” here, so it might take some experimenting. 🙂 I hope this helps!

can keeping the belly tight lead to gastroesophageal reflux(acid reflux, heartburn? b/o pressing on stomach.

So what should we do to possibly correct some issues that may have been brought about by keeping the core engaged over a long period of time? I developed a poor habit roughly around middle school (I’m 24 now) of walking around with my core constantly tight (mostly due to me be self-conscious of my stomach). I am now noticing whenever I try to consciously relax my core, it’s not only pretty uncomfortable for my “stomach” area but I *do* have issues breathing (shallow breathes, mostly diaphragmatic breathing, not lung breathing)

I would love to see the answer for this as well, since I did the same thing. Now even being pregnant I notice I’m doing it out of habit and I’m worried about the implications for my pelvic muscles.

Really good article. On point.

Thank you, Lore!