How to bend back without hurting your back

When I was little, I did gymnastics, and deep back bends like this one were easy for me. It didn’t happen because I was particularly accomplished; my spine just went there without much resistance. Some spines do, and some spines don’t. Because of that, the challenges that the practitioners face are different. Those who have a lot of mobility in their spines will need to develop stability in their yoga practice, and those who have a lot of stability can always improve on flexibility, but they probably will never be able to do things that super bendy people do – and this is perfectly fine.

When I was little, I did gymnastics, and deep back bends like this one were easy for me. It didn’t happen because I was particularly accomplished; my spine just went there without much resistance. Some spines do, and some spines don’t. Because of that, the challenges that the practitioners face are different. Those who have a lot of mobility in their spines will need to develop stability in their yoga practice, and those who have a lot of stability can always improve on flexibility, but they probably will never be able to do things that super bendy people do – and this is perfectly fine.

You are probably pretty clear by now which camp you belong to, but does your yoga practice reflect that knowledge? It’s easier to fall into patterns that are familiar to the body – for bendy people to push further into backbends and for not-so-bendy people to give up on backbends altogether. Either one is a disservice to the body. Today, we will talk about developing stability while bending back (which is important for everyone) and increasing the range of motion of the spine (for those who need it, and I don’t mean folks like that – ouch!)

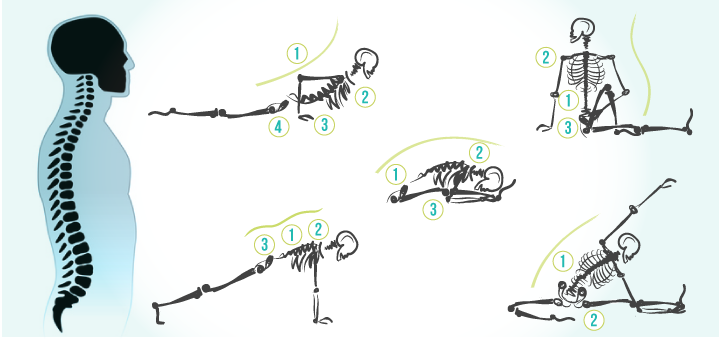

The biggest problem for most people in backbends is creating a pivot point, which means that most of the bend will be happening in one location, stressing it significantly. Can you identify the pivot points in those two poses?

Exactly, the lower back is taking on the entire load, often at the L4-L5 junction (a place between the last two lumbar vertebrae), which is the most mobile and the most weight-bearing. L5-S1 connection (where the lumbar spine connects to the sacrum) is often compromised as well. I read a quote from a spinal surgeon somewhere – he said that L4-L5 junction had bought him a nice house and put his son through college. Many people experience problems in this area. I don’t know about you, but I don’t feel like sponsoring this guy’s Porsche, so I choose to take care of my spine.

Instead of bending at a pivot point, we need to focus on distributing the curve throughout the spine. We do that by 1. Focusing on lengthening the spine instead of bending back, and 2. Creating a strong abdominal contraction when we exhale in the pose and MAINTAINING IT ON THE INHALATION.

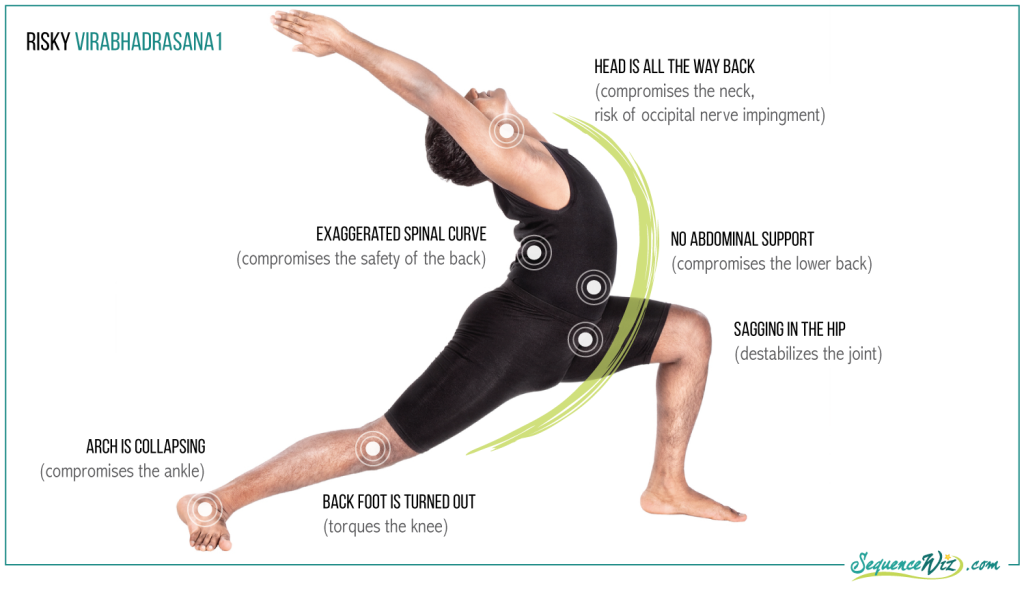

Let’s analyze those points using the Warrior pose as an example. In the first image, the emphasis is placed on deepening the curve of the spine, which compromises the body in a number of key areas.

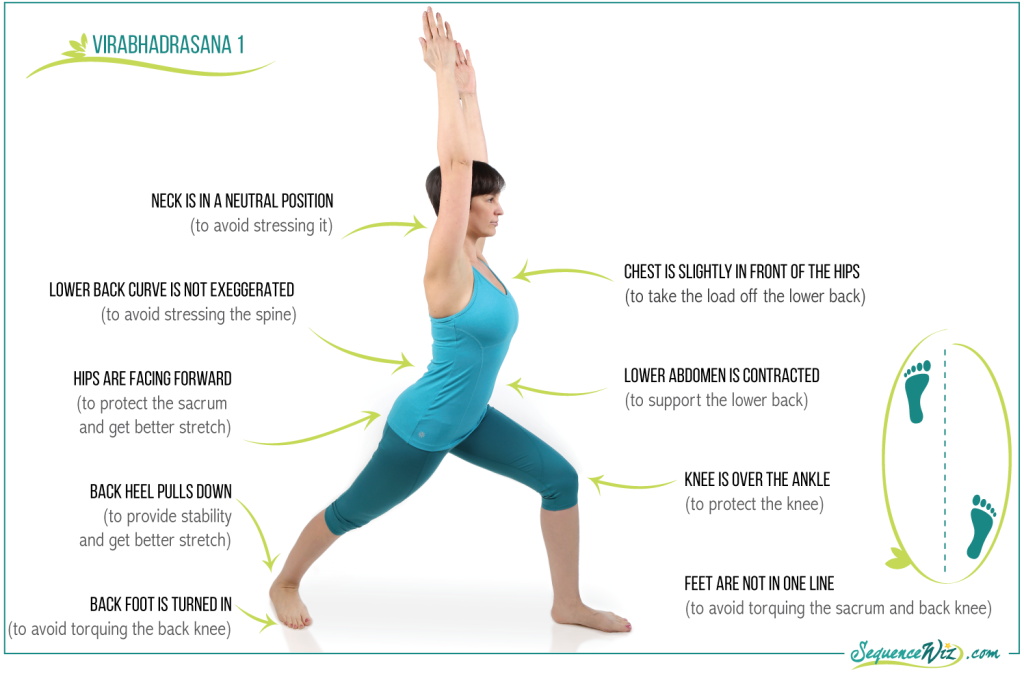

In the second image, the curve isn’t nearly as deep, but the emphasis is placed on LIFTING THE CHEST AWAY FROM THE NAVEL. That way, you get the benefits of both strengthening the back and stretching the front of the body.

When we bend back, the most important thing is to create an abdominal contraction to support the lower back. Otherwise, we end up collapsing into the lower back and stressing the spine at those vulnerable L4-L5 and L5-S1 junctions. Here is how to do it.

INHALE: Move into the pose, making sure that the chest ends up slightly in front of the hips.

INHALE: Move into the pose, making sure that the chest ends up slightly in front of the hips.

EXHALE: Gradually contract the abdomen from the pubic bone toward the navel.

INHALE: Lift the chest forward and up, away from the hips, WHILE MAINTAINING a partial abdominal contraction (the lower part of the abdomen will remain contracted).

EXHALE: Reengage the abdomen from the bottom to the top, keeping the lower body stable and grounded.

Continue to breathe like that, emphasizing the length of the spine on the inhale and abdominal support on the exhale.

Potential release valves.

In addition to bending at the pivot point and lack of abdominal support, we might encounter a few other issues while attempting back bends that might strain the student’s body. Here are a few examples:

1. Collapsing the neck backward is problematic because it creates tension on the back of the neck and has the potential to compress or irritate the occipital nerves. Those are the nerves that run from the base of the neck up through the scalp. Trauma to the occipital nerves is often caused by an auto accident where the head impacts the headrest; we don’t want to recreate a similar situation in our yoga practice. Nerve impingement can lead to headaches, pain, and burning at the back of the neck. Also, when you move your head back beyond the point of just looking up, you can put pressure on the vertebral arteries and, with that, reduce the blood flow to the brain. The situation gets worse if the arteries are clogged. The result is dizziness, and maybe even loss of consciousness.

INSTEAD: Keep your head in line with the spine in most poses. There are some poses (like the Camel pose, for example) where you take your head back; otherwise, you will stress your anterior (front) neck muscles. But even there, we need to avoid hyperextension (one way to avoid hyperextension is to lift your breastbone up so that it is parallel to the ground).

2. Shrugging the shoulders toward the ears is a common response to stress, lack of movement, and computer work (read ”modern lifestyle”). It becomes even more pronounced when we ask the arms to bear weight (like in an Upward-facing dog pose). This can lead to neck and shoulder tension and stress on the shoulder joints.

INSTEAD: Relax the shoulders when not bearing weight; lift up on your arms, rolling the shoulders back and down when the arms are bearing weight.

3. Rounding the shoulders forward creates tension in the shoulders and prevents the expansion of the chest.

INSTEAD: Focus on widening the collarbones and pulling the shoulder blades in and down, which will help with proper shoulder positioning.

Backbends can be invigorating, back-strengthening, and heart-opening, as long as we don’t sacrifice the safety of other body parts.  Back bends are excellent for both strengthening the body and manifesting different ideas within a yoga practice (like openness, vulnerability, receptivity, etc.) Check out this post that takes a closer look at Virabhadrasana 1 and shows what makes this pose so special and multidimensional.

Back bends are excellent for both strengthening the body and manifesting different ideas within a yoga practice (like openness, vulnerability, receptivity, etc.) Check out this post that takes a closer look at Virabhadrasana 1 and shows what makes this pose so special and multidimensional.

How do you know what each yoga pose is meant to accomplish? When you are clear about the purpose of each pose, you will know how to choose an appropriate pose, how to teach it, and how to adapt it to a specific student.

Another wonderful and articulate article. Thank you so much!

Thank you Barbara!

Yes! You are so right. This is me and one of the reasons I avoid yoga classes. It seems that the goal is your first illustration and I always feel inept when I can’t do it like that. In fact, right now just bending over to tie my shoes hurt- although this is because I wasn’t being faithful to the hip abductors video you have. So thank you for showing me this other way to do it. I will now include in my routine.

Hi Deborah – I am so happy to hear that you are rethinking your approach to back bends! Deeper is NOT better, which is particularly true for back bends.

Instead of BENDING BACK if we intend to stretch upward and give some imprtance in our core we will avoid hurting ourself and stop blaming the yoga and yoga teacher.

Could you please talk about the role of the glutes in supporting the lower back in poses such as baby back bend or, as in your article, Virabhadrasana 1? I’ve read an instruction that they should be “firm but not hard” (in relation to cobra) and I would like more information. For example, why not hard? Is it a general rule that we should squeeze the glutes (somewhat) when bending backwards? I’m wondering if “squeezing the glutes” is a simple way of instructing not to let the pelvis tip forward.

Thank you for all your articles; I read them avidly!

Hi Susan, thank you for an excellent question. You gave me an idea for a separate blog post – turns out I got a lot to say on the subject! For now let’s keep it simple. The job of your glutes is to move your legs back. You do that in many back bends (like Upward bow or Locust), so they will be working there. In other poses (like Camel or Bridge) they are not involved directly, but it is a good idea to contract them. I think of them in similar way I do about lower abdominal contraction when you bend forward- like an invisible hand supporting your movement. The upper body is heavy after all, and glutes are larger then your lower back muscles, so it’s nice to have their support. How much? It depends (sorry, couldn’t resist – it always depends :). I find that many people have weak glutes from sitting too much and standing with their hips thrust forward – they need to learn to engage those muscles. Other folks keep their glutes clenched all the time as a reflex and it is really hard for them to relax them. So I think when you hear that instruction “firm but not hard”, the teacher means: “Don’t clench” We want the muscles to contract, but we don’t want them to go into a spasm-like state. So I would suggest that you experiment on yourself – can you engage the glutes in the back bend? can you relax them completely when you are done with the pose? do you lean your hips forward when you stand? – that sort of thing. Sometimes I instruct my students to actively engage the glutes throughout the practice – when my goal is to strengthen those muscles. Sometimes I will ask specific students to do it if it looks to me like their pose lacks stability. I think it is usually useful to look at the entire picture and see if there is any collapse happening anywhere and troubleshoot that. Does that make sense?

Great explanation Olga. But I never know what engage means or feels like. How do you engage without clenching?

The simple way to test it: Stand up straight and lift one leg back. The glute on that side will be working. This is what contraction feels like. You can look for similar feelings in other poses. Hope this helps!

That explains so much! In a separate post (nurse your hamstrings? hip flexors?) you say “engage the glutes” in the warrior pose and when I add tension there it rotates my hip out completely undoing the sensation of stretch across the front of my body. It sounds from your words here that my glutes were already engaged (I have some pretty amazing glutes^.^), and I was just “clenching” in addition.

Images are super important for body work!

Excellent point!

Thank you for that great article, Olga. I’m glad you mentioned “Feet are not in one line” in Warrior I, I totally agree. For me, it’s almost impossible to put the feet in one line and at the same time maintain stability, and the hips squared.

However, I see many students trying to put the feet in one line – and I even heard sometimes yoga instructors saying that. Do you have any idea where that comes from (maybe a certain tradition)?

Cheers

Stefanie

Hi Stefanie; yes, I’ve seen this before, but I don’t know where this came from. Keeping the feet in one line definitely compromises stability and can be problematic for the sacrum and the back knee.

Thanks Olga, I’ll take it to mean a gentle squeeze! Glutes move the legs backwards, but when the legs are fixed, as in Cobra, and also partially in standing back bends, squeezing the glutes tips the top of the pelvis backwards. Lying in Cobra without the squeeze I get a bad feeling of hyperextension at a point in my lower back. Squeezing the glutes takes the pressure right off my lower back as it smooths out that too-sharp angle.

Thank you again and looking forward to your next articles!

Exactly. Engaging the glutes in Cobra also helps you anchor the lower body and keep the pelvis symmetrical so that it doesn’t tip sideways. Glad it was useful!

Forward bends are a happy place for me; back bends feel constricted and too many can leave me sore for days. I’ve known I need to approach them differently, but not known how. This is very helpful – thank you for the informative, detailed article and for your response to questions.

Thank you Mel! I hope that you find happy middle ground for back bends – they are so good for you! I am glad to hear that you are approaching them with caution – preventing back problems is always better then trying to resolve them later.

Hari Om Olgaji

Thanks a lot! I have corrected my approach to back bends through the ‘gyan’ from your guidance.

Engaging the gluteus during Bhujangasana, was a very important input.

Yogicly

Abhinandan

Great! Yes, engaging your glutes creates additional support.

Hari Om Olgaji

A little clarification.

The image of Veerabadrasana1 shows the working musculature of the left leg under ‘strength’ . Here, the ‘shaded’ portion does not include the musculature of the quadriceps??

Please clarify.

Yogicly

Abhinandan

Hi Abhinandan, are you referring to this post: http://wp.me/p4q4vp-182 ? You are absolutely right; I updated the image to reflect the quadriceps engagement. Thank you for catching it!

I also have a question about your images: in the correct demonstration of warrior 1, you show the back foot as pointing forward, but at about a 30º angle compared the the front foot. In your foot placement diagram to the right, you have both feet roughly parallel — does that mean that there is a range of acceptable “forward point” for the back foot?

You are exactly right -there is a range here. The most important thing here is to keep your hips facing forward. Turning your back foot in so that the toes of both feet are pointing in roughly the same direction helps with that. Some folks cannot do it (for variety of reasons), so it’s OK to keep the toes of the back foot pointing slightly outward.

I went to do a backbend and for some reason my back starts hurting

Not many emphasise on such details. You are doing wonderful job. I am incorporating your ideas in my teaching.