How to organize a practice around yoga breathing

One of my guilty pleasures used to be watching Project Runway. Intense interpersonal drama aside, it was amazing to see all those very different designers manifest their creativity through clothing. Maybe I didn’t always agree with the judges or see what they saw, but I could still appreciate the harmony of the look even if I would never put it on myself.

One of the common critiques designers receive on that show is, “There are too many ideas here.” This is when you make a dress with ruffles, add some fringe, cover it in sparkles, and wrap it all up in tulle. I guess it could work (if Nicki Minaj was wearing it), but more often, it doesn’t.

For some reason, in yoga classes, this seems to be a good thing. More often than not, I observe teachers trying to include absolutely everything they can think of in a class. I attended a class not too long ago where the teacher was very sweet and full of best intentions. And I guess in her eagerness to satisfy every possible need, we did some upper body strengthening, some heart opening, some core strengthening, and some deep twisting peppered throughout with talks about the meaning of OM, deer hunting, overcoming inner obstacles, Thich Nhat Hanh and the anniversary of JFK’s death, all packed in an hour-long class. While I really appreciated the teacher’s attempt to integrate the dimensions of yoga beyond the physical, it was just wa-ay too much going on to keep track.

That is one thing that really stuck with me from my viniyoga teacher training many years ago: in any yoga practice, ONE element is always dominant. If you want to make it asana, that’s fine. Then, breathing can support it, along with meditation and other things. If you want to make the breath a dominant element (which would make sense for multiple reasons that we will discuss later), then the asana and other things play a supportive role. Otherwise, the practice can become an example of “everything but the kitchen sink.” You can organize your yoga practice around an idea, meditation, chanting, ritual, or mudras – whatever you think will help you manifest your intention for the class, as long as it’s ONE main thing. Today, we will focus on designing breath-centered practices: why do them, what options to choose, and how to plan them.

Why would you want to have breath as a dominant element?

1. To increase breath awareness in certain parts of the body (chest, belly, sides of the ribcage, middle back, diaphragm).

Every time you breathe in, your chest and your belly are supposed to expand at the same time; when you breathe out, they should return back to the original shape. This natural pattern is often altered because of some sort of breathing restriction or unconscious holding patterns. Whenever possible, the natural pattern needs to be restored, and the most direct path to that is becoming aware of how different body parts move with the breath.

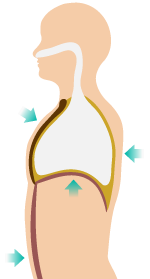

2. To increase breath capacity or length/depth of Inhale or Exhale.

We’ve already established that the depth of the breath is the single most reliable indicator of one’s longevity. Long, deep breaths help oxygenate the body properly so that all its systems function at their best. Anybody could benefit from increasing their breathing capacity. On the other hand, certain breathing disorders, like asthma, COPD, and others, make it difficult for the person to either inhale or exhale. When designing a therapeutic practice for a situation like that, we would focus on the part of the breath that is more difficult and work on making it more comfortable.

We’ve already established that the depth of the breath is the single most reliable indicator of one’s longevity. Long, deep breaths help oxygenate the body properly so that all its systems function at their best. Anybody could benefit from increasing their breathing capacity. On the other hand, certain breathing disorders, like asthma, COPD, and others, make it difficult for the person to either inhale or exhale. When designing a therapeutic practice for a situation like that, we would focus on the part of the breath that is more difficult and work on making it more comfortable.

3. To work on sympathetic/parasympathetic balance.

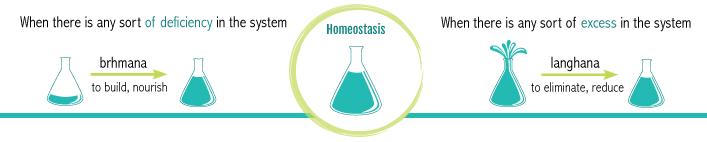

We spent a lot of time talking about our fight-or-flight (SNS) and rest-and-digest (PNS) modes. If you are interested in revving up your system for the upcoming challenge, you would want to increase the sympathetic activation. If you want to slow things down and unwind, you would use yogic tools for parasympathetic activation. In the yoga tradition, we use the Brhmana/Langhana paradigm to make it happen. It is especially useful when you are working with three pillars of physiological health: Energy levels, Sleep issues, and Stress management.

4. To work with any physiological condition (digestive/circulatory/immune, etc.)

Any time a student faces a physiological challenge, yoga breathing practice is always the first thing we reach for. Remember, breathing is one physiological function that is under our conscious control, so it serves as a doorway into our physiology. Depending on the situation, we might choose from a variety of yogic models: Brhmana/Langhana paradigm for excess/deficiency, Chandra/Surya paradigm for temperature management, Pancha vayu model for the patterns of energy flow, etc.

When you organize your practice around yoga breathing, it usually means including some sort of breathwork when doing your poses AND formal pranayama practice. Pranayama practice cannot pop out of nowhere at the end of the class. You need to know from the beginning that you will do it at the end and prepare your student’s body, breath, and mind accordingly. We do it for difficult postures; why wouldn’t we do it for the breath? This will require planning ahead and making conscious choices throughout the practice.

If you want a lasting sense of stability, consistent energy, and resilience, you need to integrate pranayama into your regular yoga practice. Here is how to do it for maximum effectiveness.