How do you know which way is up? The innerworkings of your vestibular system

“No matter which way our head is turned, regardless of the direction and speed of our movements, we have to be able to distinguish up and down, forward and backward, left and right, even while running zigzags, jumping up and down, spinning in circles, or turning cartwheels. That ability starts with our vestibular system.” (1)

The vestibular system accomplishes the remarkable feat of telling the brain which way the ground is and which way you are moving every moment of every day, yet it is so tiny that it fits into an area the size of a pea. The structures of the vestibular system are very small and very delicate, yet crucially important to everything we do. Let’s take a quick look at the main parts of the vestibular apparatus so that we could appreciate the remarkable work that happens behind the scenes and get a better understanding of what might go wrong.

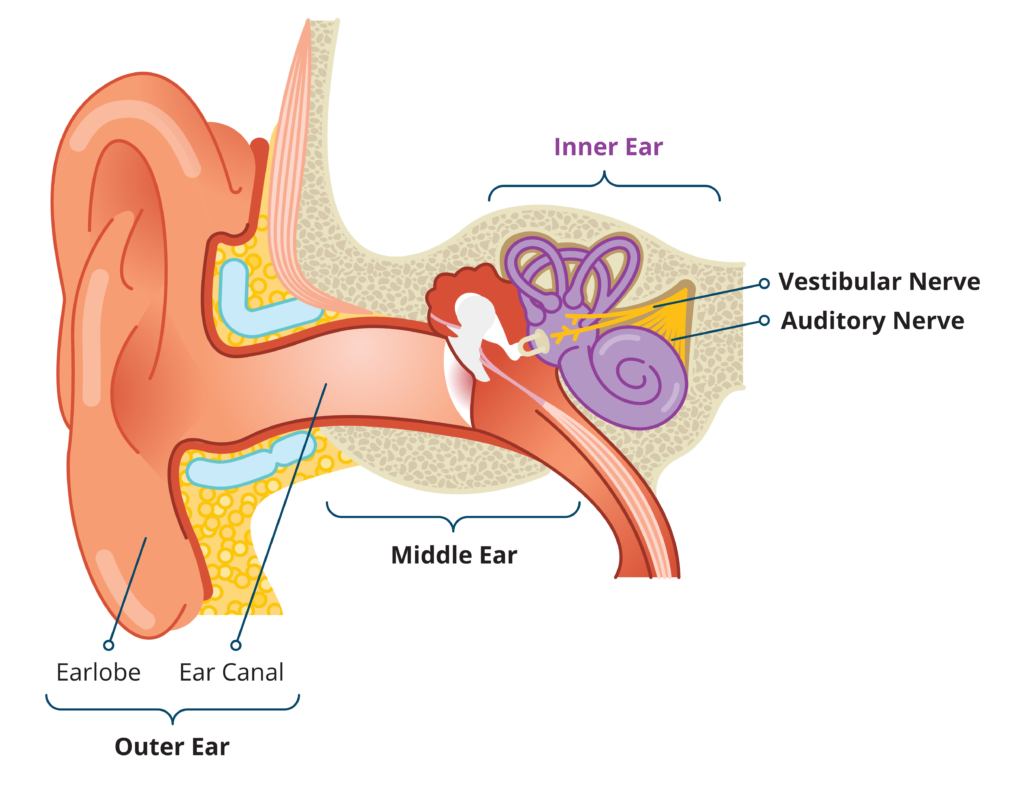

This is what your ear looks like.

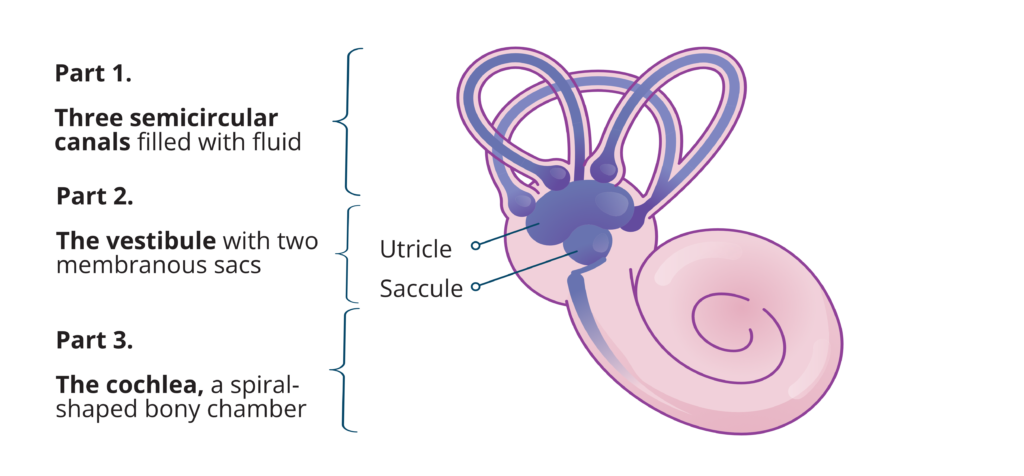

The sense of equilibrium is handled by the inner ear, that looks a bit like a snail. The inner ear consists of three main structures.

Part 1. The semicircular canals are three tiny looping tubes set at close to 90-degree angles to each other in 3D. Within them are hollow semicircular ducts that are filled with fluid and contain tiny hair cells that are active during movement and quiet when the body is still. The semicircular canals are positioned at an angle to one another so that the receptors within them can detect the movement in three rotational planes. Horizontal rotation, as shaking your head “no” stimulates the hair cells within one of the ducts, nodding “yes” excites the cells in another duct, and tilting your head from side to side activates receptors in the third duct. Even the most complex movements have these three components within them.

The movement of the hair cells within the ducts is detected by the vestibular nerve, which sends this information to the brain. The brain processes this information, and this is how you know the position of your head. This happens very fast in a perfectly functioning vestibular system. This is why, no matter how fast you move your head, the brain keeps track of which way is up.

Part 2. The vestibule consists of two membranous sacs: the saccule and the utricle. The sacs are filled with liquid and it’s the same liquid that flows within the semicircular ducts. The receptors in these sacs provide the sensation of gravity and linear acceleration.

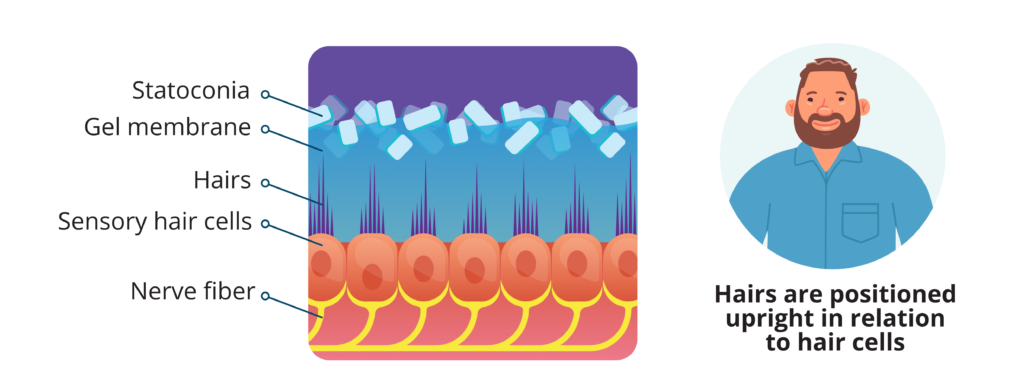

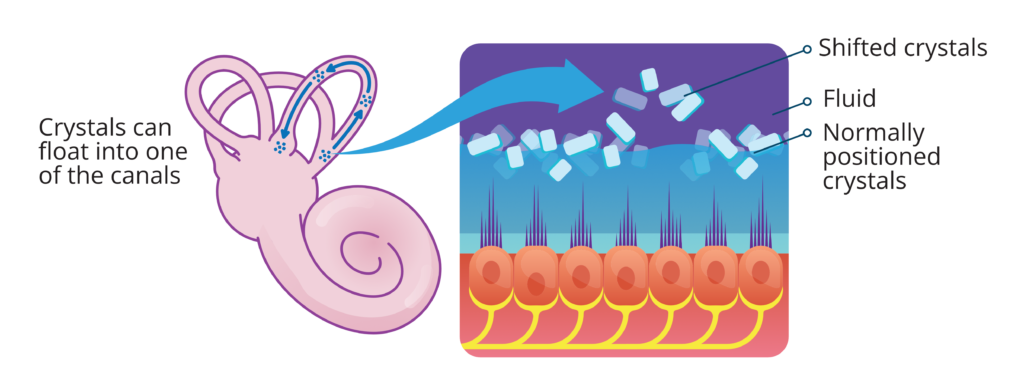

The hair cells within the saccule and utricle are embedded in a gelatinous goo. On top of it are pilled-up densely packed calcium carbonate crystals called statoconia (or otoconia). Each crystal is very small, about one-tenth the size of a salt crystal. The utricle lies horizontally and the saccule lies vertically.

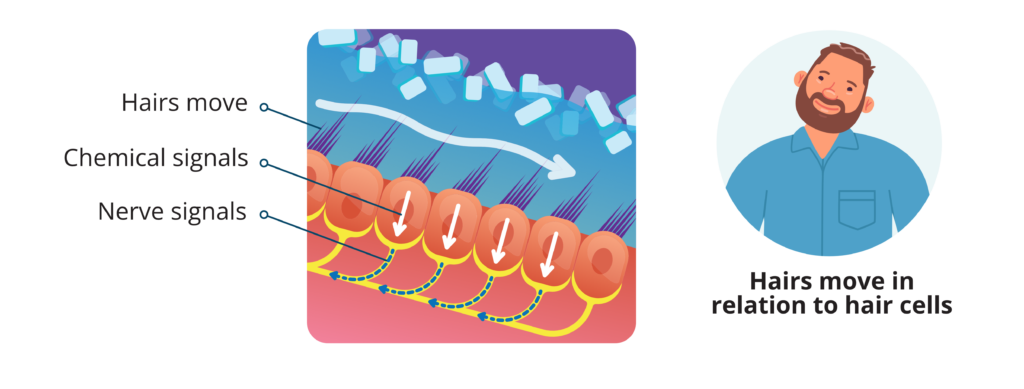

The crystals naturally fall in the direction of gravity. When you move, the crystals move and fall, squishing the gelatinous membrane underneath, which then bends the underlying hair cells. The cells send that information via the nerve fibers of the vestibular nerve to the brain. That way, the brain always knows which way is down.

These same crystals make us sense linear motion, like when the vehicle you are in suddenly accelerates, and your head feels thrown backward.

To summarize, the structures of the semicircular canals detect the movement of the fluid within them and, based on that, provide information about the rotational movement of the head; the structures of the vestibule detect the movement of the little crystals in relation to gravity and give us information about which way is down, linear movements, and acceleration, as well. Together, these two structures are called the vestibular complex.

Part 3. The cochlea is a spiral-shaped bony chamber. The receptors within the cochlea provide the sense of hearing. The cochlea is not directly involved in the maintenance of equilibrium, but sound can affect our sense of balance.

When things go wrong

A properly functioning vestibular system is essential to our ability to stand and move. There are different kinds of disorders of the vestibular system, but the two most common ones are dizziness and vertigo. Dizziness is a feeling of light-headedness that you might feel when you stand up too quickly or bring your head up after keeping it down for a while. Dizziness is often connected with the blood rushing in or out of your brain.

Vertigo is something very different. Vertigo is a feeling of the room spinning around you or a sense that you are spinning even if you are standing still. Vertigo can occur for different reasons and can be a sign of something more serious going on. One type of vertigo is due to the tiny crystals in your ears floating from the vestibule into semicircular ducts, where they don’t belong. The weight of those crystals alters how the fluid moves within the canal, which sends false signals to the brain that you are moving, even when you are totally still. The mismatch between the vestibular system and the feedback from your eyes and proprioceptive receptors (that monitor the body’s position in space) results in vertigo, nausea, and lack of balance.

There is a particular kind of vertigo called BPPV (Benign paroxysmal positioning vertigo) that causes brief episodes of mild to intense dizziness. This type of vertigo often responds very well to a series of head movements called a modified Epley maneuver or the canalith repositioning procedure. This procedure helps remove the crystals from the circular canals and return them to where they belong. The challenge is that you need to know which canal has been affected and modify the movements accordingly; otherwise, you can make things worse. That’s why, if you experience vertigo, it is important to get a proper evaluation from a specialist who can check if you have BPPV, assess the positioning of the misplaced crystals by analyzing your eye movements, and guide you in the Epley maneuver properly.

For more interesting facts about balance, strategies for balance training, and balance-specific yoga practices, check out our new yoga series, Find Your Equilibrium: Yoga for Balance Training.

In this yoga series, we combine Western knowledge of kinesiology with yogic methodology to train our sense of equilibrium, strengthen the body, build integration between different body parts, and develop spatial orientation. This yoga series includes 28 yoga practices and a 58-page e-book.

Resources

- Balance: A Dizzying Journey Through the Science of Our Most Delicate Sense by Carol Svec

- Fundamentals of Anatomy and Physiology by F. Martini

- What is the home Epley maneuver? by John Hopkins Medicine