Gas exchange within the body: Don’t rush to get rid of carbon dioxide

Two years ago, my family and I went to the beautiful San Juan Islands. The San Juan Islands are an archipelago of about 170 islands in the Pacific Northwest between the state of Washington and Vancouver Island, British Columbia. A ferry picks up cars and passengers at the Anacortes Ferry Terminal and shuttles them from island to island, as some folks get off and some get on, and it eventually returns back to Anacortes with new passengers.

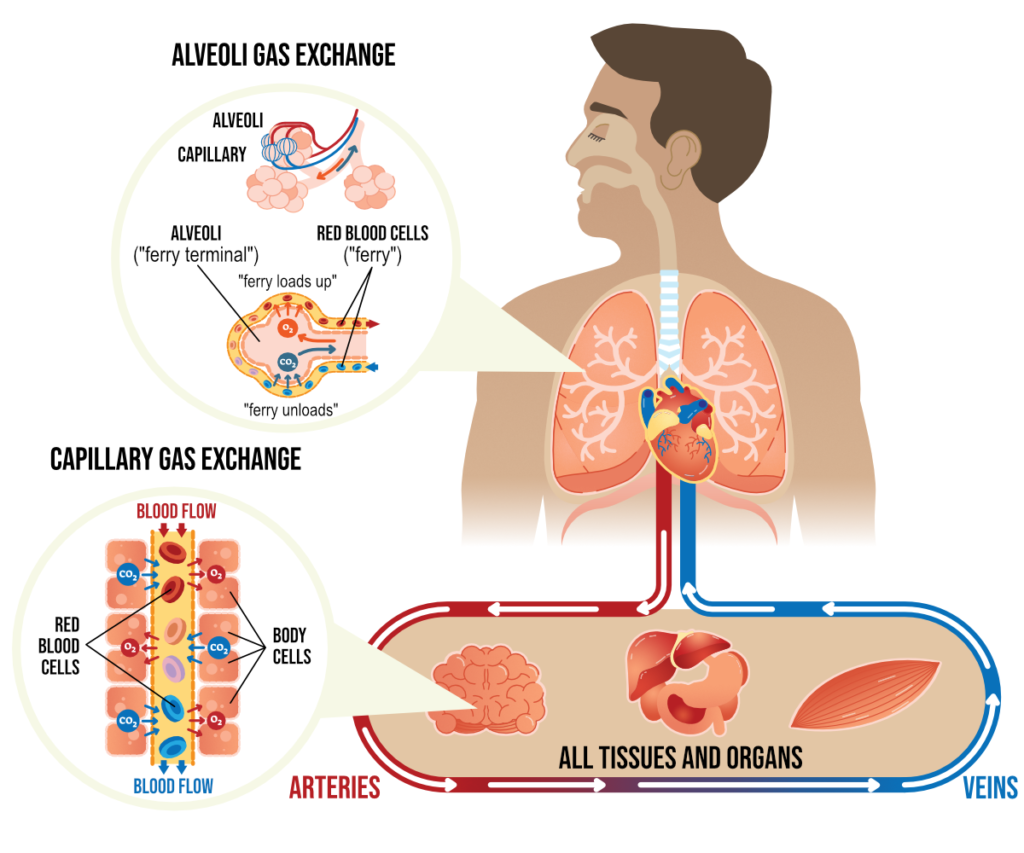

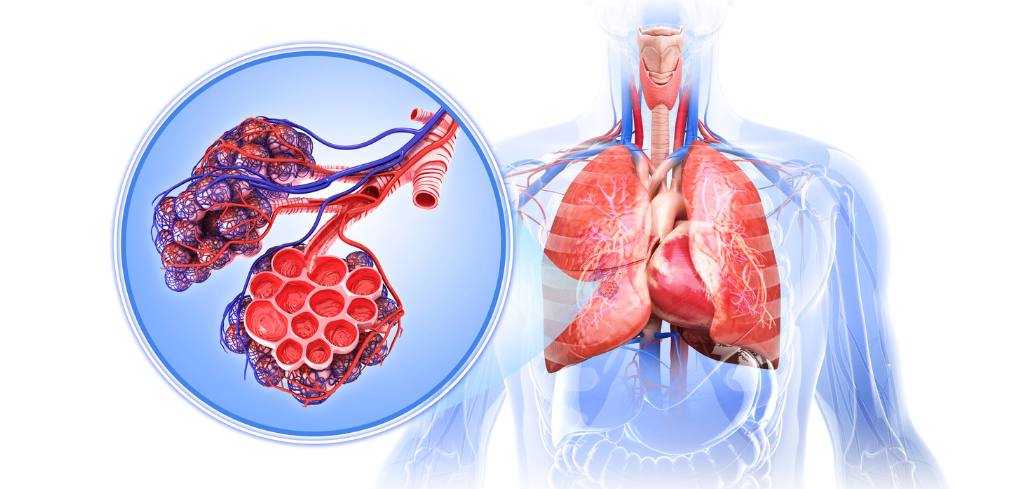

A similar thing happens during the process of gas exchange within our bodies. When you inhale, red blood cells dock in the alveoli (tiny air sacks in your lungs), the oxygen molecules (O2) hop into the cell, and then those molecules get carried by the blood throughout the body to all the cells that need them. As the oxygen molecules disembark, new passengers, carbon dioxide molecules in different chemical forms, hop on and continue on the journey until the ferry returns back to the starting point (the lungs). The ferry I was on took several hours to go round trip; in our bodies the whole trip takes about a minute (!)

There is an important factor that affects how many O2 passengers can get on the ferry of your blood cells – molecules of hemoglobin. You have 270 million molecules of hemoglobin within each cell, and each hemoglobin can carry four molecules of O2. In total, you have about a billion (!) molecules of oxygen boarding the ferry with each trip.

Here is an interesting and important fact – hemoglobin is not in a hurry to release its O2 passengers once they get on board. Like a family traveling with kids, the parent won’t let the kids get off the ferry by themselves unless grandma is meeting them. For hemoglobin to release its O2 molecules to the tissues, there needs to be a sufficient amount of carbon dioxide (CO2) available in the blood. CO2 molecules help free up O2 molecules from hemoglobin and then hop in their place to journey back to the lungs. This means that to properly oxygenate our body, we need to have sufficient levels of CO2 in our bloodstream.

You might have heard your exercise or yoga instructor urge you to “rid yourself of all that carbon dioxide!” on exhalation. This is neither possible nor advisable. Carbon dioxide (CO2) plays various important roles in the human body, including regulating the pH balance of blood, dilation of smooth muscle tissue to ensure proper organ function and protection from damage caused by free radicals. In the human body, carbon dioxide is formed as a waste product after your cells are done metabolizing carbohydrates, fats, and amino acids. This process is known as cellular respiration. Cellular respiration is the primary source of ATP, which gives your body the energy it needs to function. The body needs to maintain a very narrow range of CO2 (between 38 and 42 mm Hg) to function properly. It gets rid of excess CO2 by breathing it out.

The levels of O2 and CO2 in the body are intricately linked. “If CO2 concentrations are low, there is an increased affinity of hemoglobin to carry O2. This is known as the Bohr effect. On the other hand, if O2 concentrations are high, there is an increased capacity to unload CO2 from the tissues. This is known as the Haldane effect.” (2) The precise balance between O2 and CO2 is tricky to maintain. Whenever we fall into a pattern of rapid breathing, we tend to overload the system with O2, which cannot be properly absorbed by the body (since there is not enough CO2 to free it up from the hemoglobin). As a result, all those oxygen molecules that crowded the ferry of your blood cells end up riding for the entire round trip and get off at the initial dock (via exhalation) without ever entering your cells. The levels of CO2 in the blood drop, which has far-reaching consequences. It is particularly problematic with conditions like asthma.

Asthma is an immune system sensitivity that usually gets triggered by an external factor: dust, pollen, environmental pollutants, viruses, cold air, and so on. Once the inflammatory response begins, it immediately constricts the airways and causes hypersecretion of mucus. Since the airways become restricted, it becomes harder to push the air out, which means that air gets trapped inside. It brings with it a feeling of breathlessness, so the natural response is to try to breathe in more, and the person begins to hyperventilate. “They don’t need any more oxygen, but consciously or not, people start to take deeper breaths — and that makes the symptoms worse,” – says Dr Alicia E. Meuret, a clinical psychologist at Southern Methodist University, Dallas. “In essence, they are taking in too much air. But the sensation that they get is shortness of breath, choking, air hunger, as if they’re not getting enough air. It’s almost like a biological system error.” (3)

Dr Meuret and her colleague Dr Ritz had conducted studies on how using behavioral therapy in conjunction with daily asthma medicine can improve patients’ lung health over the long term.

When somebody begins to hyperventilate (take short, gulping breaths in), the usual advice is to “take a few deep breaths”, but it turns out that this is the opposite of what they need. The doctors instead trained their study participants to take shallower, shorter breaths to raise their levels of carbon dioxide (CO2) in relation to O2. “This study goes to the heart of hyperventilation — which is deep, rapid breathing that causes a drop in CO2 gas in the blood. That makes a person feel dizzy and short of breath,” Ritz said. “Patients in our study increased CO2 and reduced their symptoms.” (3)

The researchers also observed that people with asthma already had a tendency to breathe in too much even when they were not experiencing symptoms. This created a vicious cycle of chronically low CO2 levels, which made them feel breathless, which made them breathe in more, and so on. After training the participants to take shallower and quieter breaths while monitoring their CO2 levels with a hand-held device over a four-week period, the researchers “saw improvement in asthma symptoms and control, better lung function, reduced oversensitivity of the airways and less use of reliever medication, as well as improvement in physiology and the pathology of the airways.” (3)

Since the balance between O2 and CO2 is important, how long should our inhalation and exhalation be? Is there a magic number? Turns out there is!

References

- Breath: The New Science of a Lost Art by James Nestor

- Physiology, Carbon Dioxide Retention by Shivani Patel; Julia H. Miao; Ekrem Yetiskul; Sapan H. Majmundar

- Asthma patients reduce symptoms, improve lung function with shallow breaths, more carbon dioxide by Science Daily

- Restoring Prana by Robin Rothenberg

Ah! Such great writing. Love your articles:-D!!

Ann

Thank you Ann! 🙂

…don’t leave us hanging…magic breath count..I was diagnosed 6 months ago with adult on set asthma,(mild) doc said extremely unusual for my age, so i’m just learning about it, and as a yogini for over 4 decades i’ve always been a deep/long diaphragmatic breather, thus shallow chest breathing is not something i have much experience with, so i’m wondering if by chance …chicken or the egg, did I bring asthma on because of what you are describing

I don’t think that there is an easy answer out there. We will talk about the preferred breath count next time, but I don’t know if it will be a solution for you, considering that you’ve already been practicing yoga for so long. I would suggest that you look into Buteyko breathing methodology if you really want to investigate your latest diagnosis. They talk a lot about CO2 tolerance and balance between CO2 and O2 and how it manifests, and focus specifically on asthma. Not all of what they say aligns perfectly with what we do in yoga, but it definitely gives you some new avenues for investigation.

Thank you so much for taking your valuable time to respond, I will look into buteyko not familiar with it. I’ve also looked into food allergies and dust, mold, and other pollutants in my home environment AND there is a correlation to this late onset asthma!

Also wearing a mask when walking wheter in the santa monica mountains hiking trails or the neighborhood has helped protect the numerous air contaminants from reaching my lungs. Little silver lining with COVID requirements.

Great information on these last few posts that is pertinent to a situation I’m faced with.

My boyfriend is suffering with digestive issues that causes him to burp incessantly. I’ve introduced him to your diaphragm information and tried to work with him demonstrating diaphragmatic breathing to calm this response using your had gestures as a teaching tool. I’ve also demonstrated restorative heart opening poses to free the diaphragm. Unfortunately, he refuses my advice and instruction and swears it’s just digestion associated to diet. I do concur with that; however, stress, the diaphragm, food and poor eating habits seem to be interrelated.

I know this from experience as I am healing myself from debilitating late onset migraines addressing all the above issues. Finding your site was a blessing as I love Yoga and it’s traditions; however, we’re brainy by design and knowing why we do the poses and relating them to the science is “gold”.

Thank you,

Thank you Shannon! I am grateful to hear that you find the information I pose here useful in your ongoing exploration of your migraines. I know it can be difficult when our loved ones are not receptive to the information in the same way, but all we can really do is lead by example, right? 🙂

Such valuable information always. Thank you

Thank you Elvia!

Wonderful and clear information that is finally beginning to reach the yoga world. It’s not easy to convince people that healthy breathing involves the equilibrium between O2 and CO2 and is not a matter of loading up more oxygen. I always think of it as a bus driving though neighborhoods. If a neighborhood is poor in CO2 ( also a product of exercise ) , the bus doesn’t stop and O2 doesn’t get off.

I took a Buteyko training in 2017 – no more panic attacks and so much more endurance.