External factors that are messing up your sleep: Part 2

Last time, we discussed the two most important factors that can interfere with sleep quality and quantity: light and temperature. Both of those factors affect the release of melatonin, a hormone that signals to the brain that it is time to go to sleep.

Other external factors that impact our brain chemistry are caffeine and alcohol. Caffeine artificially mutes the effect of adenosine – a chemical that gradually builds up in the brain in the course of the day, creating “sleep pressure” in the evening that makes you fall asleep. It can take 5-7 hours to overcome a single dose of caffeine and succumb to “sleep pressure.”

Alcohol, on the other hand, is a sedative, and it will eventually put you to sleep. Initially, it sedates your prefrontal cortex, which is responsible for decision-making and moderating social behavior. As a result, you become a bit less inhibited. Then alcohol sedates the rest of you. Unfortunately, according to Matthew Walker, PhD, “alcohol sedates you out of wakefulness, but it does not induce natural sleep. The electrical brainwave state you enter via alcohol is not that of natural sleep; rather, it is akin to a light form of anesthesia.”(1) As a result of this “alcohol sedation” the sleep often becomes fragmented, which means you get less rest. Even if you don’t notice those brief awakenings, you will feel their impact in the morning. (Have you ever felt refreshed and energized in the morning after an evening of heavy drinking? Probably not.) Alcohol also robs you of dream sleep, which means that you will forgo all important brain activity that happens during deep sleep and is essential to the processing of your emotional experiences and finding creative solutions to your problems. To avoid “alcohol sedation,” you can either limit your intake of alcohol or have your drink earlier in the day (unless you are working or operating heavy machinery). Now you have a scientific justification for that Sunday brunch Mimosa or Bloody Mary. 🙂

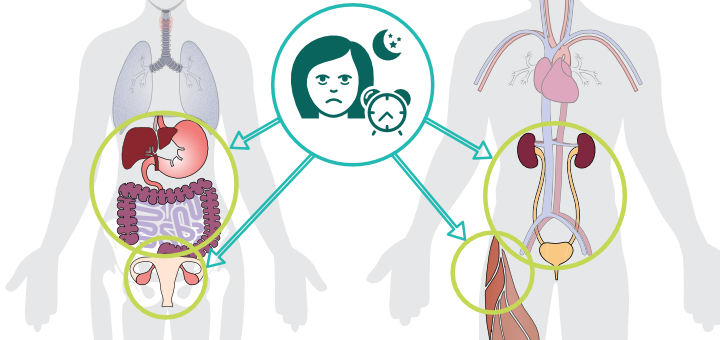

Another factor that predictably affects your sleep quantity, as well as your body’s physiology, is your alarm clock. Matthew Walker, PhD, who has studied the impact that alarms have on our bodies, reports: “Participants artificially wrenched from sleep will suffer a spike in blood pressure and a shock acceleration in heart rate caused by an explosive burst of activity from the fight-or-flight branch of the nervous system.”(1) The alarm is startling to your heart. And if you continue to hit the snooze button repeatedly, you will subject your heart to that shock over and over again. The best solution is, of course, to let yourself wake up naturally (which often isn’t realistic). To minimize the stress that the alarm places on your heart, you can try other types of alarm. For example, there are alarms that wake you up by slowly turning on the light to imitate sunrise. Something like that would be much more kind to your heart. On the other hand, if the sun is already waking you up way too early in the morning, you can manage it by blocking the early morning light with either blackout curtains or a face mask. Of course, there might be other reasons for early morning awakenings.

Another factor that affects your sleep is of particular interest to us as yoga teachers. It concerns exercising before bed. While having a regular exercise routine can generally improve sleep quality, it is not recommended that we exercise too close to bedtime (and that includes our asana yoga practice). According to Matthew Walker, “body temperature can remain high for an hour or two after physical exertion. Should this occur too close to bedtime, it can be difficult to drop your core temperature sufficiently to initiate sleep due to the exercise-driven increase in metabolic rate. Best to get your workout in at least two to three hours before turning the bedside light out.”(1) This is why whenever we design a home yoga practice for a student, we always need to know – when does she plan on doing it? What is she trying to accomplish with it? If she wants practice to help her fall asleep, she will need to do it close to bedtime but keep active movements to a minimum with more emphasis on breath work and meditation. If she wants a strong physical practice, she would need to do it at least three hours before bedtime to avoid adversely affecting her sleep.

These are some of the main external factors that can impact our sleep. Matthew Walker sums it up nicely: “Beyond longer commute times and “sleep procrastination” caused by late-evening television and digital entertainment—both of which are not unimportant in their top-and-tail snipping of our sleep time and that of our children—five key factors have powerfully changed how much and how well we sleep: (1) constant electric light as well as LED light, (2) regularized temperature, (3) caffeine, (4) alcohol, and (5) a legacy of punching time cards [alarm clocks]. It is this set of societally engineered forces that are responsible for many an individual’s mistaken belief that they are suffering from medical insomnia.”(1) The good news about external factors is that most of the time, we have control over our environment.

Let’s take a look at some physiological reasons for poor sleep and discuss some common-sense strategies for dealing with them.

References

- Why do we sleep: Unlocking the Power of Sleep and Dreams by Matthew Walker