Is it better to be flexible or stable?

Many years ago, when I just started teaching yoga, I wanted to make sure that my students got enough stretching. One time, a good friend of mine took my class. “How was it?” – I asked afterward. “It was fine, – he said – it just felt a bit passive. All those deep stretches close to the ground made me feel like a wet noodle; I’d rather feel strong.” “Ouch,” – I thought at first but then reflected on it a bit more. Are physical strength and flexibility mutually exclusive? Or are they complimentary? And how can we find the right balance?

The human body is organized around a skeleton, which forms its structural center. However, the skeleton doesn’t possess its own structural integrity. It would be just a pile of bones on the ground if it weren’t for our ligaments (that connect the bones), tendons (that connect muscles to bones), and muscles (whose job is to keep the body upright and to move it). All those parts are linked together by fascia – connective tissue that covers the muscles, merges with tendons, and wraps the bones.

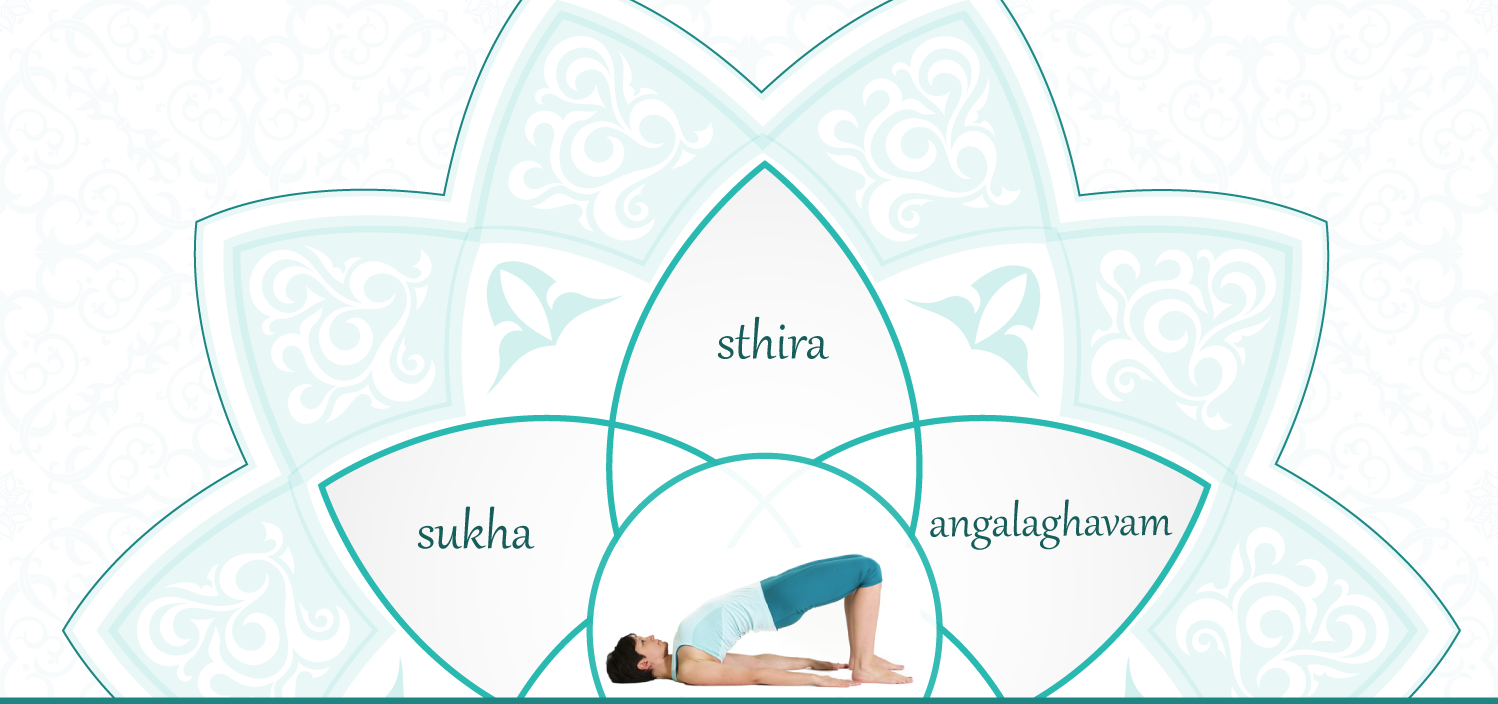

The purpose of this intricate arrangement is to keep the entire structure together so that we are able to stand upright (on two legs!) and move in a variety of ways, all within gravitational pull. The structure needs to be stable enough not to collapse yet flexible enough to allow for the body to move freely. Let’s take a look at each one of those elements to figure out what we want from them in the flexibility/stability department.

Bones

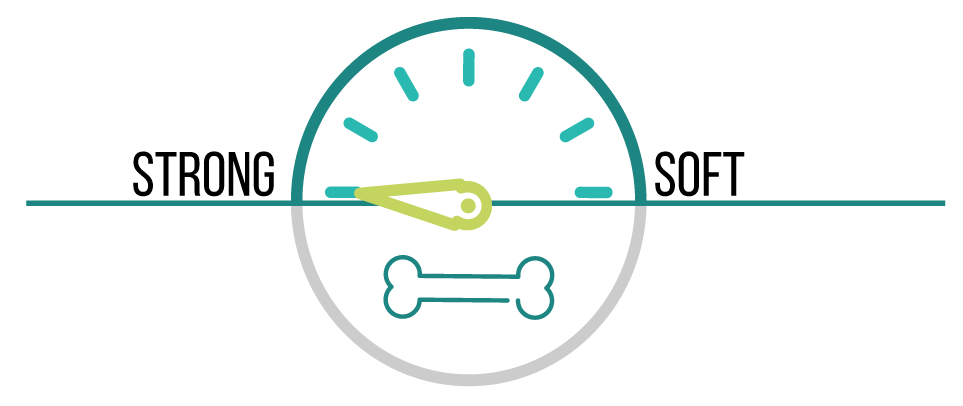

Since the skeleton forms the main structural support of the body, we need it to be strong (nobody wants spongy or brittle bones). The bones become thicker and stronger by adapting to new stresses from muscle contraction that pulls on the bones. That’s why strong, weight bearing yoga poses are beneficial here, not the stretchy ones.

Ligaments

We are all born with certain predispositions – some of us have shorter ligaments that contribute to the sense of stability but somewhat limit the range of movement; others have looser ligaments that enable a greater range of motion but compromise stability. Those who have tighter ligaments from birth might never be able to do a full Lotus pose, but does it really matter if they are able to maintain structural integrity? Those who have loose ligaments can flop into contortionist poses with ease but might have trouble maintaining proper alignment and can have their joints pop out of place (especially the sacroiliac joints).

We do have some wiggle room within our congenital situations, but some things will remain out of reach forever. A person with a tighter structure can work on increasing her range of motion and will succeed in expanding that range (mostly by working with fascia), but she will never be able to do the same leg-behind-the-head things that her loose-ligament neighbor can do. And the loose-ligament person can train her muscles to support her weight in stronger poses, but her ligaments will never get shorter, and she will never be as stable as her tight-ligament neighbor. Each person is dealing with her own set of challenges, and we all benefit from recognizing our structural situations and working with them, instead of fighting them.

Muscles

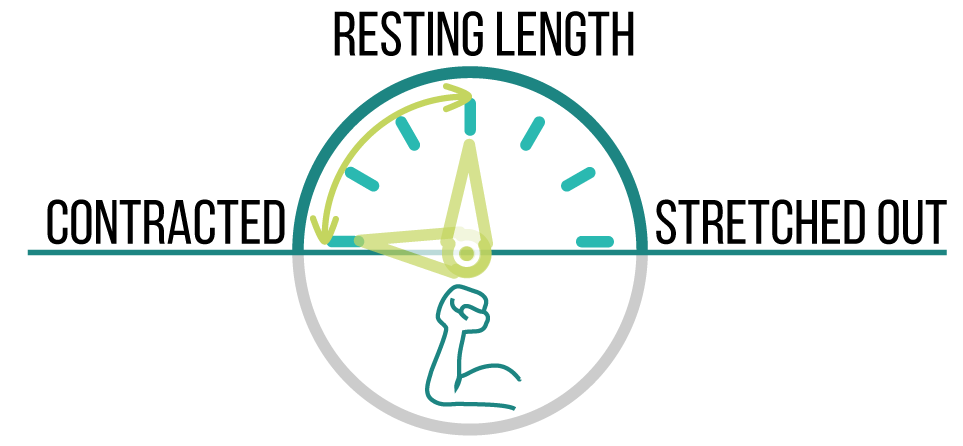

With muscles, we are mostly interested in maintaining their contractile power, which means that the muscle can shorten when loaded and relax when not loaded. Muscles don’t stretch; they tear. The sensation of release that you get after a deep stretch is your muscle returning to its resting muscle length. The muscles can get stuck in a contracted state, making you feel tight and stiff, or they can get stuck at their resting length, which will make you feel weak and trembling while attempting to do a strong move. In either situation, the solution is to contract the muscle first (to restore its contractile power and release tension), then relax it, and then stretch it gently (not for the purpose of making the muscle longer, but for the purpose of restoring the resting muscle length). We call it the “contract-relax-stretch” sequence.

Fascia

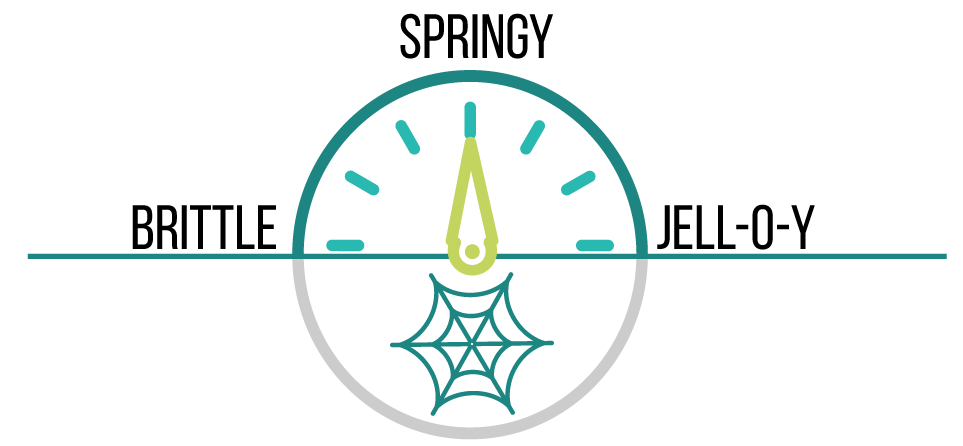

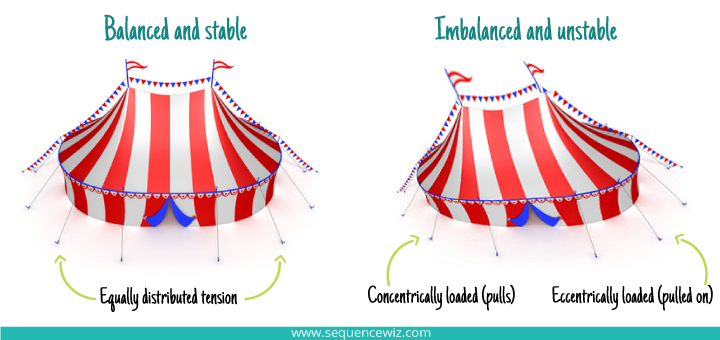

Fascia is the connective tissue that serves both as a bag that holds muscles, bones, organs, etc, and the packing material in between those structures. Fascia links all physical structures together and transmits mechanical tension across multiple structures. There will ALWAYS be tension along myofascial meridians because this is how the body organizes its multiple parts, remains upright, and maintains its mobility (just like a circus tent needs equally distributed tension along all the ropes to remain upright).

Fascia is a major contributor to the whole body being “stuck” in a posture that you assume for most of your day and asymmetries resulting from habitual movement patterns. The body adapts to the load you put on it, creating the patterns of unequally distributed tension. Those patterns need to be corrected – not by stretching the tight areas, but by moving the body often and moving it in a variety of directions. That is why, in a yoga class, we usually include forward bends, back bends, side bends, twists, and axial extension postures to encourage the balanced distribution of tension along myofascial meridians. This keeps the fascia properly hydrated and allows it to do its job effectively.

As you can see, at every level of our physical bodies, there is a constant interplay between stability and flexibility, and stability is usually a more desirable quality. And what is flexibility anyway? It is a combination of looser ligaments, good muscle tone, and hydrated fascia. Looser ligaments depend on Mother Nature, and good muscle tone is achieved by contracting, relaxing, and then gently stretching our muscles to restore their normal resting length and increase the range of motion in the joints. Varied and frequent whole-body movement takes care of fascia.

Certain movement combinations work every time to release tension in specific body areas, and simple yoga practices based on those movements give students reliable relief from their physical tensions.

I found your blog last week after researching information on what I believe to be a hamstring injury. I was not properly warmed and stretched I assume. (I had run 5 miles -lots of hills, tried a bit of plyometrics for the first time and then an hour of yoga. Toward the end of my yoga sequence I do the splits, followed by some inversions. I have been doing the splits regularly for a few years. This time however I must have done something wrong because my hip/rt leg sounded as if a chicken bone was being torn apart at the thigh leg juncture. The pain was electrifying and I immediately got out of the pose. I have been unable to do anything much since. No running, no yoga, it is painful to walk as though I did a serious workout the day before. It seems to be improving. My doctor prescribed methylprednisolone which I haven’t taken. There’s pain (4/10) but nothing 2 Advil can’t help with. Your blog sequences seem to be the answer to coming back to full use. My question is how much longer should I let it heal without stretching or exercise and what are your thoughts on the methylprednisolone use? BTW, I’m in my fifties and this happened a little over 2 weeks ago.

One of your best posts, ever, Olga!

I agree 🙂

Dear Olga, I read what you write with great interest and pleasure… thank you so much for your so well presented writings. I am so happy to pass them on… they are wonderful THANK YOU

Hi Olga

thank you for this great article….Even though I regularly remind my students that we are all physically different. I only wish I had read your article and reminded MYSELF before I tried to get my leg behind my head and blew out my knee 😀

Oh, you tried that too….leg behind the head act. Yep, I did, too. I ended up going to a chiropractor for the first time in my life. I think I blew out my lower back. No more!

I really appreciate the ideas that you’re presenting here. Thank you so much for the clear & simple explanations!

Great as al way se ?

I currently read a book about anatomy and fashia and find it hard to understand as I am not in the medical field. Just a a passionate yogi. Your article is clear and easy to understand! Thank you very much Olga!