How to align the body in balancing postures

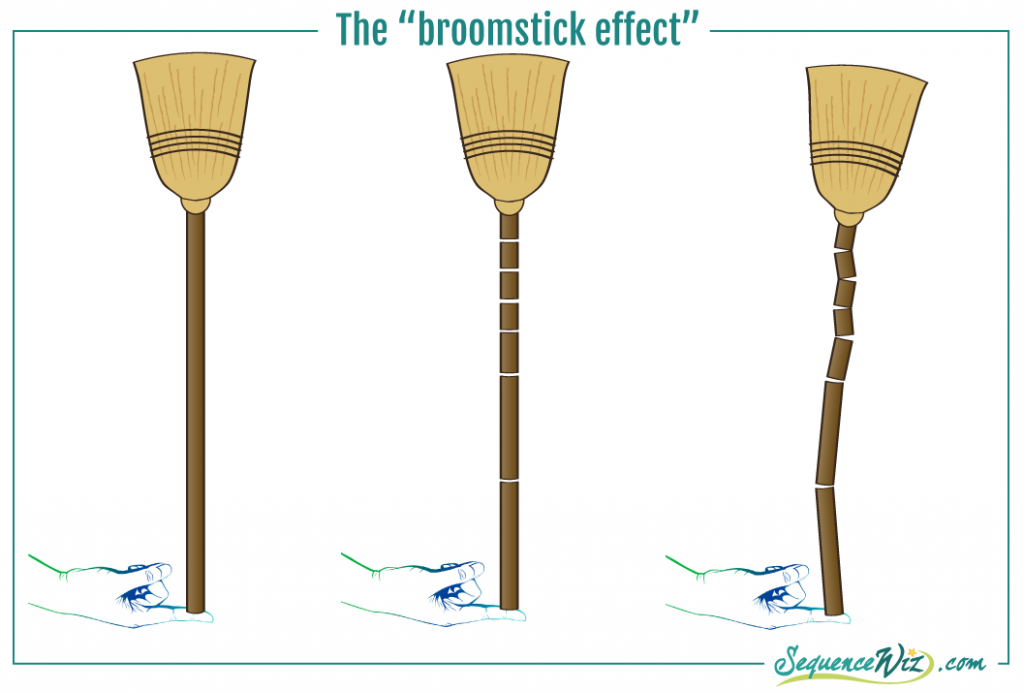

Many years ago, I read an article on balance in one of the yoga magazines, and one visual that the author used stuck with me. She talked about trying to achieve “broomstick effect” when it comes to aligning the body in balancing postures. Here is what it means.

Imagine trying to balance a broom on your finger. When you do that, you watch the broom and try to predict in what direction it will lean and move in the same direction to even out its position. This is not too hard of a task because the broom is in one piece. Now imagine that instead of being one piece of wood, the broomstick consisted of several different pieces with somewhat loose joints between them. Now, if you try to balance that broom on your finger, you would have to pay attention to each individual segment, trying to figure out where each segment will lean and how it will affect the entire structure. This is much more difficult.

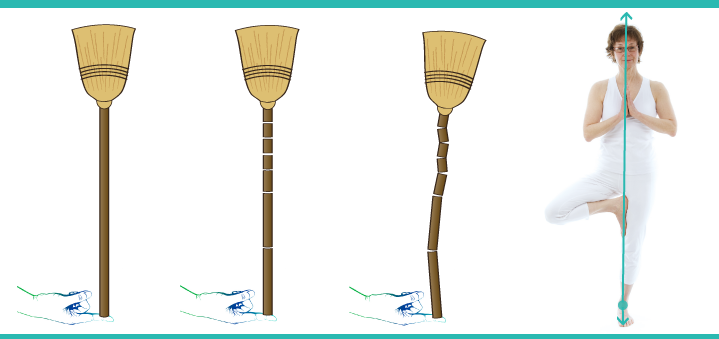

It works the same with your body in the balancing posture. Our bodies are not sticks; they have many joints, including ankles, knees, hips, and all the joints between the vertebrae. If you let your body be loose while you try to balance on one leg, for example, you would have to monitor the position of each individual part and where it ends up in relation to other parts. This is a lot of work. What would be easier? To turn your body into a broomstick! It doesn’t mean that we would want to stiffen it up and tense up the muscles. Instead, we would want to create maximum length, just like we do in axial extension postures. It means that we would want to lengthen up along the axis, creating length and stability in the body and minimizing the wobbliness of individual parts. That way, the body becomes an integrated whole, a unit that is much easier to manage. Then, your main focus would be on your foot and ankle. They would negotiate the balancing action and make necessary adjustments to maintain balance.

That is why when we prepare for any balancing posture, we focus on creating a sense of length in the body via axial extension postures. On top of that, for specific types of balancing postures, we do additional preparation:

– For leg balancing postures, we spend a lot of time warming up and strengthening the ankles

– For arm balances, we warm up wrists and shoulders

– For arm-leg balances, we warm up the hips, wrists, and shoulders

– For seated balances, we prepare the hips (especially the hip flexors) to counterbalance the weight of the upper and lower body.

This principle works really well for static poses that teach the body to maintain balance. But this is not as applicable to teaching the body how to regain balance when we slip or trip.

Let’s discuss the differentiation between static and dynamic balance and how it educates our approach to yoga practice design.