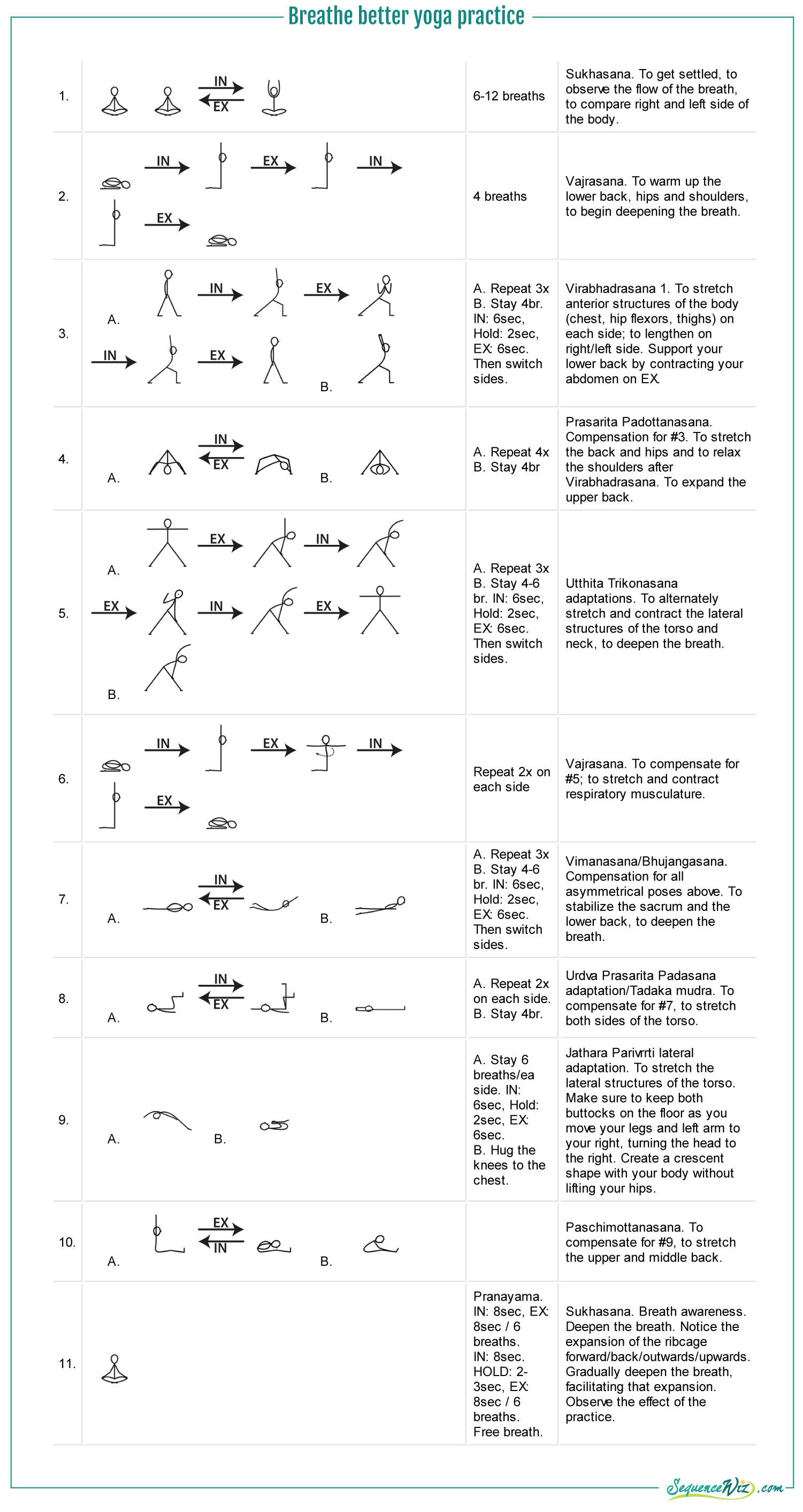

Breathe better yoga practice

One of the most common misconceptions I encounter regarding breathing is that many students think we can move our lungs at will. This is not the case – the lungs do not have muscular tissue, so we cannot operate them directly. In fact, the lungs behave more like a rubber band. The lungs’ outer surface sticks to the ribcage’s inner side and to the diaphragm, and the lungs get pulled (stretched out) following the movement of those structures. “But at the same time, they [lungs] resist this type of stretching, and as soon as the force ends, they return to their original shape.” (1)

That is why inhalation is generally shorter and/or more difficult for most people—a certain force needs to be applied every time you inhale to stretch the lungs out, and they will resist this stretching. The action of exhalation, on the other hand, is one of elastic recoil—the lungs return to their original shape, just like a rubber band.

Even though we cannot move the lungs directly, we can affect their expansion indirectly by engaging the muscles of respiration that wrap around the ribcage. During relaxed everyday breathing the diaphragm does most of the work (assisted by gravity if you are standing). When you are exercising or attempting to breathe deeply, the inspiratory muscles have to work harder, and the tension and elasticity of the lungs increase. “When you inhale a lot of air, those actions are at their maximum.”(1) If you pause after the inhale, the inspiratory muscles will continue to contract, resisting the lungs’ pull to recoil.

When inspiratory muscles get tight, they cannot do the work of the ribcage elevation and expansion efficiently, making breathing harder. Subsequently, the lungs don’t stretch out as much and don’t hold nearly as much air as they could.

We’ve already established that deep breathing is essential for efficient blood-oxygen exchange, sustained energy release, proper organ function, restful sleep, stress management and longevity in general. That is why it’s worth your while to spend time and effort exercising your respiratory muscles both via movement and deep diaphragmatic breathing with hold after inhalation (we call it “breath retention”). The practice below does just that – give it a try and let me know how it feels!

Reference

1. B. Calais-Germain Anatomy of Breathing

It’s a pretty well-known fact that breath regulation is the most obvious way to control our sympathetic (“fight-and-flight) and parasympathetic (“rest-and-digest”) balance, which directly impacts our stress response, sleep patterns, and energy levels.

if I may add

The more natural and easy way of breathing is with the diaphragm. If you look at a just born baby you’ll see how he is breathing with his belly naturally. Breathing with the diaphragm consumes much less energy and therefore is less tiring than breathing with the chest muscles.

But unfortunately, because of stress and way of life, most of us (including myself) forget this breathing and breath with the chest muscles..

Hi Oded – this is certainly true! It is also true that we use other respiratory muscles more when we exercise of if our oxygen demands increase for some other reason. And I agree – chest breathing is not ideal!

Your website and teachings are excellent. I particularly enjoy your calm pleasant presentation and would strive to achieve a similar presence as a very newly qualified teacher. ? i have especially enjoyed this routine over the last week as it has helped me manage a congested cold . Love your work,! Barbara, Australia

Thank you Barbara! After years of teaching I discovered that using my normal voice and talking how I normally talk works best in my yoga classes as well – what a revelation, right? 🙂 I am sure you will develop your own style and build your confidence as you go – practice is the only way we get there 🙂

Hi Olga,

Thank-you so much for all these wonderful video practices, it is a pleasure to sometimes be lead through a practice that addresses a specific need. I have trained in the same tradition of practice with A.G Mohan, Indra Mohan and Ganesh Mohan, unfortunately there are no classes in my area that I can attend, everything is “Dynamic Flow, Goddess, Ashtanga, Yang-Yin Yoga, Bikram…..” Now, thanks to you I can attend a class whenever I wish to and even choose the practice that most suits my present needs!

I am also picking up lots of useful teaching tips and asana variations to pass on to my students, thank-you very much Olga you are helping teachers to help students everywhere 😀

Thank you so much Louise, I am so happy to hear that! Personally, I prefer purposeful practices and sometimes do my own videos when I feel like being a student myself 🙂

Hello Olga,

I really appreciate your sequences and careful explanations of why we move our bodies as you recommend.

A correction, though. You wrote, ” The outer surface of the lungs sticks to the inner side of the rib cage and to the diaphragm, and the lungs get pulled (stretched out) following the movement of those structures.”

That is incorrect.

The lungs are separated from the structure of the rib cage by a thin sheet of membrane called the pleura.

The lungs are attracted to the ribs because of an area of negative pressure in the space which separates them. When the muscles of respiration contract, this creates negative pressure inside the lungs, which pulls air in. When you exhale there is positive pressure inside the lungs, thus air goes out.

The diaphragm is attached to the xiphoid process of the sternum, the coastal margin of the thoracic wall, ends of ribs XI and XII, ligaments that span across structures of the posterior abdominal wall; and lumbar vertebrae

Hi Matt! Thank you for your contribution; I am aware of those facts. I do not see how what I wrote contradicts what you say though. Here is a direct quote from the Anatomy and Physiology text by F.H. Martini: “A fluid bond exists between the parietal pleura and the visceral pleura covering the lungs. As a result, the surface of each lung sticks to the inner wall of the chest and to the superior surface of the diaphragm. As a result, movements of the diaphragm or rib cage that change the volume of the thoracic cavity also change the volume of the lungs.” My goal here on the blog is not to write an anatomical manual, but rather to simplify the anatomical complexity so that it is accessible to many. Thank you for reading!