Does yoga have its own approach to meditation?

At a holiday party a couple of weeks ago, I was having a conversation with a lovely young woman who turned out to be a certified meditation teacher. After hearing that I was a yoga teacher and also taught meditation, she asked me: “What kind? Buddhist? Transcendental?” This reminded me of the sad reality that the general public has no idea that yoga has its own rich meditation tradition. My teacher Gary Kraftsow used to joke that even at yoga conferences, they tend to teach “asana and Vipassana.” There is nothing wrong with the Vipassana style of meditation, but it is a different tradition from yoga, and we should recognize it as such. Today, we will take a closer look at the yogic teachings of meditation derived mostly from the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali.

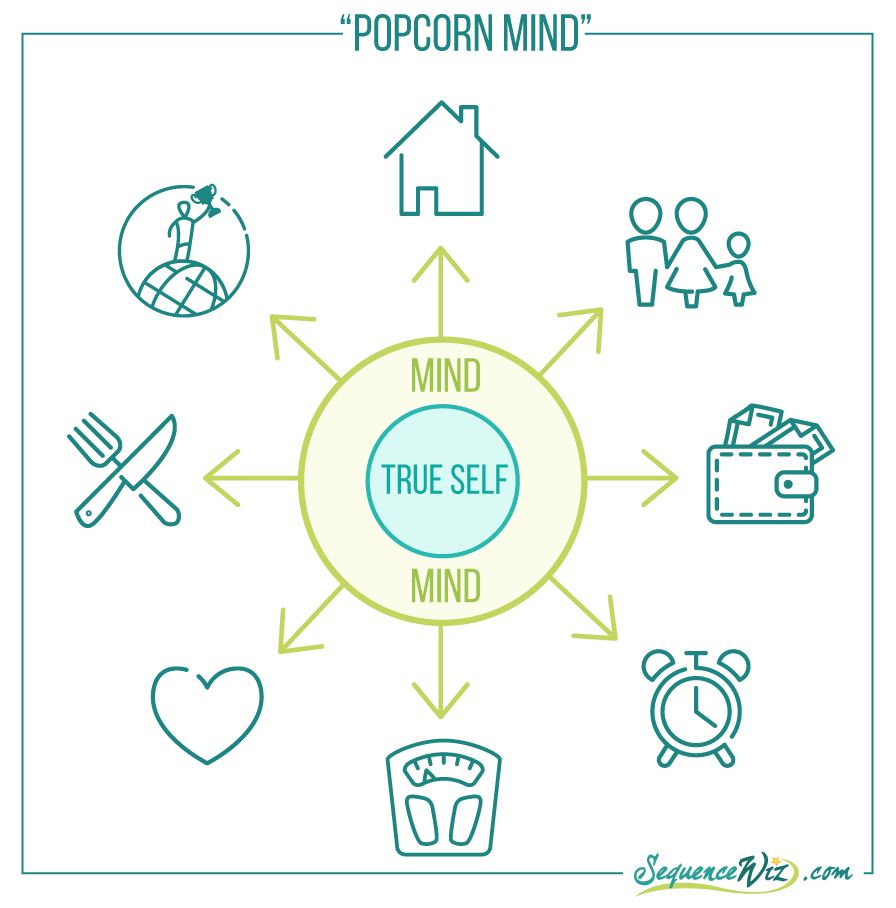

According to the yoga tradition, our minds tend to fluctuate between the states of attention and distraction.

This is a normal pattern that can be called “popcorn mind” (not a traditional term :), when different thoughts pop in and out, holding our attention for a bit and then switching to something else. There are many different things we are usually concerned with in our daily lives, and our thoughts follow those recurring themes.

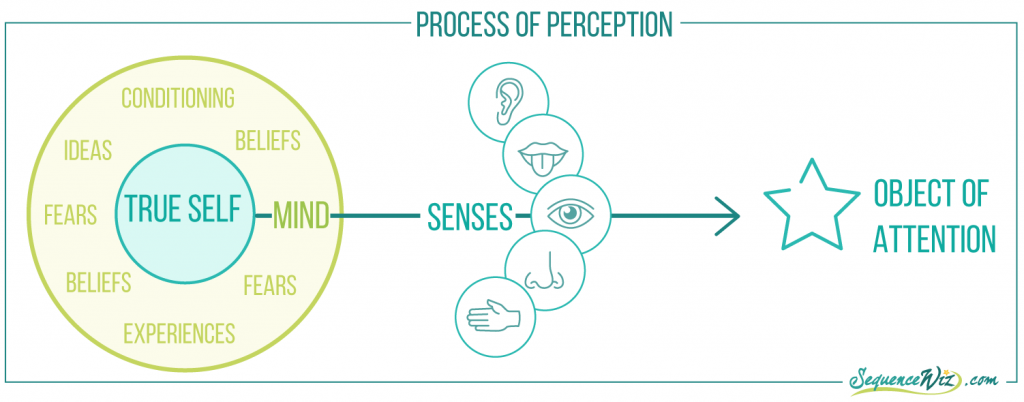

We perceive the external reality through our senses and then filter it through our minds.

Because of that filter, we rarely perceive an external object the way it is. When I look at a suitcase in my bedroom, it is never just a suitcase. It can be a source of frustration (as in “My husband left this monstrosity here again that I trip over every time I need to open the closet”), a source of excitement (as in “Yay, we are going on vacation soon!”) or anything else from a huge range of associations, memories, and projections.

We perceive our internal reality via interoception, which includes awareness of our bodily functions like breathing or heartbeat, and the thought process itself. Those internal perceptions get filtered through the conditioned mind as well, with all its biases.

According to yogic teachings on meditation, either an internal or external object can become an object of meditation. In the beginning, meditation serves the important purpose of training our focus and teaching us to concentrate on one thing for an extended period of time (developing a one-pointed focus). Later, we can use meditation to begin to differentiate between the object itself and our biases around the object and eventually question our assumptions and conditioning.

There are three stages of meditation: dharana, dhyanam, and samadhi.

First step: Dharana

Dharana (-dha- “to hold”) means being able to hold attention on an object for progressively longer periods of time without distraction. For example, you can hold your attention on the light of a candle or the rhythm of your breath for an extended period of time.

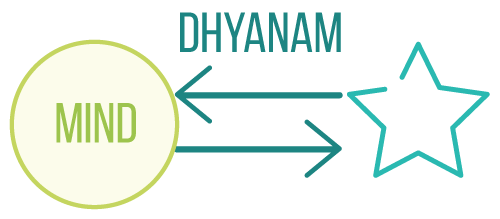

Second step: Dhyanam

Dhyanam (-dhi- “to reflect”) occurs when there begins to be a relationship between the mind and the object of attention. It means that you gain some insights about yourself from concentrating on the object. For example, by meditating on an image of fire in your belly, you gain insights into your ability to process your experiences.

Third step: Samadhi

In the state of Samadhi, the relationship between the object and the mind becomes very close, as if they have merged. At that point, the mind begins to shed its conditioning, and the object shines forth as it is. For example, if you meditate on a deity in the state of Samadhi, you take on the qualities of that deity.

At that point, according to Patanjali, instead of being clouded by your baggage, the mind becomes like a transparent crystal, able to reflect the object perceived, the instrument of perception (the mind), and the process of perception. When you get to that stage, you are no longer bound by your biases and are able to see reality for what it is (neither good nor bad) and yourself for what you are (unchanging True Self). Ultimately, meditation is about cleansing the filter of your perception.

For many of us, the very thought of going inward is terrifying. What kind of murky stuff are we going to find? Why stir things up?

Dear Olga, your posts are always so helpful, interesting, full of content and knowledge. I love receiving your emails. This one is especially well done with all those graphics. Thank you so much from Germany!

Thank you Godula! I am so happy to hear that it resonated with you!

Once again, Olga, you manage to explain principles of yoga in such a clear manner, making it more palpable and usable in our daily western life. Thank you for sharing your pedagogic gift with the yoga community with such generosity.

Dear Olga, thank you for your posts and I now look forward to many more.

Dear Olga, thank you for taking the time to share your knowledge and exceptional teaching skills with us. I look forward to these posts and have learned so much from you. Please know how much you are appreciated!! OM

Thank you. I will apply when I am teaching. Sharing insight to others while moving so is not too intimidating.

Just a simple question. Why do you use the case ending Dhyanam (am) for Dhyana? While you do not use any case endings with Dharana or Samadhi?

Hi Rhonda! I’ve seen it spelled both way, but my teacher Gary Kraftsow teaches it as “Dhyanam”. He knows Sanskrit much better than I do, so I just go with that. I never really asked him why, but next time I see him I will 🙂

There is a ‘physicality’ to meditation that fits well with the discipline of yoga. The ancients held insights into the significance of the ‘mind/body relationship many eons ago, while western medicine has only relatively very recently begun confirming these understandings scientifically. However subtle and mysterious this relationship may be, yoga practice has the potential to demonstrate that quality of thought, is indeed influenced by the quality of ‘action’.

Yoga is much beyond asanas. Swami Vivekananda has given excellent knowledge on the various types of Yoga which should be studied by every practitioner.

Swami Satyananda Saraswati & Swami Niranjananda Saraswati are also good sources to study the place of meditation in the overall family tree of Yoga.

Meditation is always though of as part of and never separate from Yoga.

And ultimately, meditation is a state of being/existence, rather than a method/process/act.

Excited for your next pose! As a beginning teacher, I am loving your blog posts and resources. Question: What is the relationship of “Vipassana” then, to this description? Thank you!

“Vipassanā in the Buddhist tradition means insight into the true nature of reality. In the Therevada tradition this specifically refers to insight into the Three marks of existence: impermanence, suffering or unsatisfactoriness, and the realisation of non-self.” Vipassana is a Buddhist tradition and while some aspects are similar to yoga, it comes from a different lineage. I don’t know much about Buddhism to comment on specific differences, but it is a case of “mixing models”. It usually works better to stick with one model while trying to explain one’s take on reality, otherwise we might end up confused 🙂

oops…Olga, EARLY buddhism isn’t only about Vipassana in fact all the techniques you mentioned were part of Siddharta’s meditation “curriculum”.

Dharana corresponds to Samatha / Kammathana which understands at least 40 different supports for onepointed focus. Dhyanam corresponds to combining insight with onepointed focus. And finally Samadhi corresponds to Jhana or meditative absorption. Now the background is APPARENTLY different seeing that in Yoga there’s the Self, whilst in Buddhism there is no Self which is replaced by sunyata or radiant emptiness (here between us to me there is no difference 😉 …)

Thank you for your explanation Jose!

So many of the very first comments above resonate with my sentiments exactly after reading this post, Olga. Again and again, thank you and thank you.

Thank you Kevin!

Thank you Olga for all the effort that you put into your posts. They are much appreciated and highly valued.

Thank you Maggie!