Why the foot pain is connected to the neck pain: your movement patterns shape your body

In the yoga world, if we get pain somewhere in the body, we take it as a call to action and begin to stretch that particular area. This approach is often ineffective because, in the words of prominent physiotherapist Diane Lee, “It’s the victims who cry out, not the criminals.” This statement requires a fundamental shift in perspective – just because something is hurting doesn’t mean that it is the source of the problem. Now, why is that? Why does the old pain in your right foot eventually shows up as tension in the neck? This happens because of fascia.

Fascia is the cotton candy-like connective tissue that for hundreds of years had been carefully scraped off by anatomists to expose muscles and bones and considered irrelevant. In the last couple of decades, however, fascia has been reclaiming its role as a vital whole-body communication network.

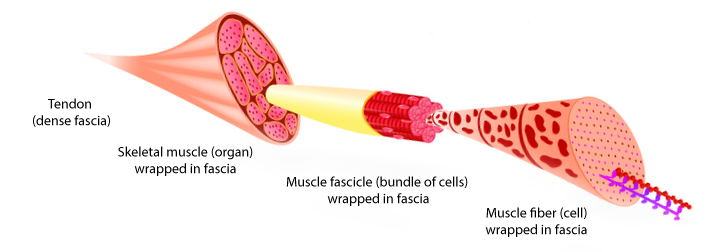

So what is fascia, and why should we, yoga teachers and practitioners, care about it? Fascia is the connective tissue that serves both as a bag that holds muscles, bones, organs, etc, and the packing material in between those structures. It is comprised mostly of collagen fibers. For example, when you look at an individual muscle, you will see that fascia wraps individual muscle fibers, groups of fibers, and muscle as a whole, becoming denser toward the end and forming a tendon, which then seamlessly blends into the fascia that envelops the bone.

“Without its [fascia’s] support, the brain would be runny custard, the liver would spread through the abdominal cavity, and we would end up as a puddle at our own feet.” (1)

The fascial system is an all-pervading physiological network; it is as important as the circulatory and nervous systems. It is a vast and truly fascinating subject; if you are interested in how the body works. Here we will focus on two qualities of fascia – its continuity and its ability to transmit tension.

As yoga teachers, we always concern ourselves with the idea of connection (hence the definition of yoga as “union” or “linking”), yet we often fall into the mechanistic view of the body as a system of levers and pulleys. We tell students that “this pose stretches this muscle,” as if anything in the body works in isolation. In the world of fascia, the muscle is linked to the bone, which is linked to the ligament, which is linked to another bone, and then a tendon and another muscle, etc. It’s perfectly fine to study muscle action, characteristics of ligaments, etc., as long as we remember that they are all part of an interconnected fabric within the body and affect each other constantly.

Beyond linking everything to everything, fascia has an important role of communicating mechanical information by the interplay of pulls and pushes. Just like a snag on a sweater can run across the fabric, the tension is transmitted in the same way from one place in the body to another via a fascial net. A human body is a constant interplay of internal and external forces that need to be balanced and distributed. As a result, there are predictable patterns of tension throughout the body that are necessary to keep us upright and allow a wide range of movement. “Strain, tension (good and bad), trauma, and movement tend to be passed through the structure along these fascial lines of transmission.”(1)

To describe those predictable lines of tension, Thomas Myers adopted the term myofascial meridians (not to be confused with acupuncture meridians – a bit different). A myofascial meridian basically describes a line of tension that runs through a sheet of fascia that connects and envelops several muscles. I can’t help but think of a silly cartoon from my childhood of a cat and a dog pulling on a sausage link.

It is kind of like that. The casing of the sausage link is like fascia, while muscles form the contents. When it’s pulled in the opposite directions, tension is created that is transmitted throughout the entire length.

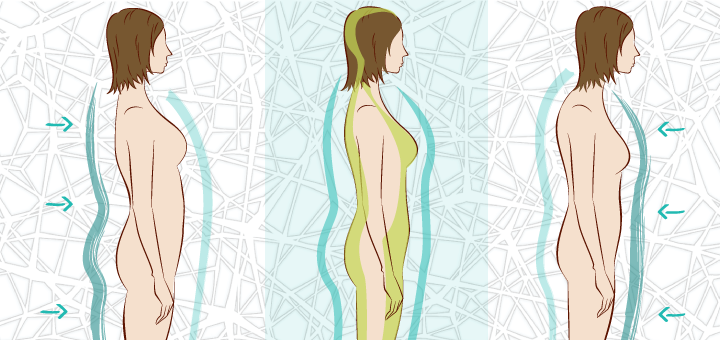

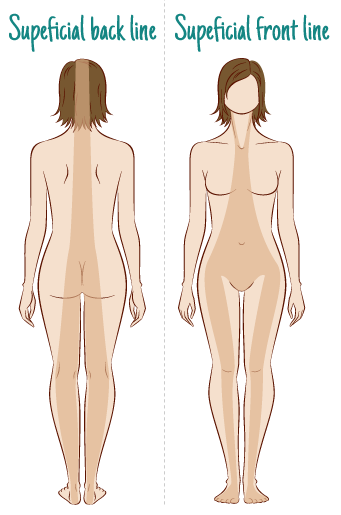

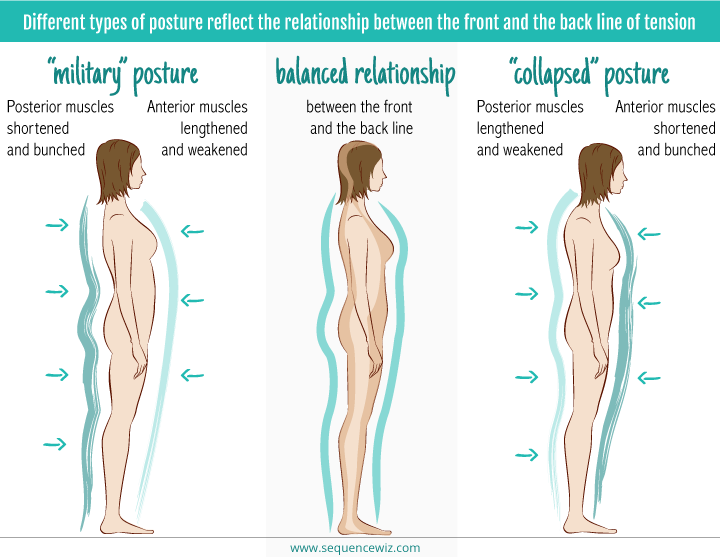

Let’s take a look at two “cardinal “ myofascial meridians: Superficial front line and Superficial back line. Just by looking at them, it is obvious that SBL and SFL need to balance each other to support the upright position. If the SBL becomes too tight and shortens, you will end up with a “military” posture with some or all posterior (back) muscles shortened and bunched and the anterior (front) muscles pulled and strained.

Or the reverse can be true as well in a “collapsed” posture with a rounded thoracic spine and flattened lumbar curve. The military posture might come with tight hamstrings, but if you only focus on stretching the hamstrings, you won’t resolve the issue. This is where we need to look at the body wholistically (as a whole) and identify the patterns of tension that run throughout.

Some patterns of tension are predictable because of the body’s organization; others are unique because of the movement patterns, past injuries, etc. Basically, your body responds to the loads that you put on it. For example, one of my former students who spent 30 years driving a forklift in this position developed his own unique pattern of tension that spiraled around his body and manifested as severe hip and sacrum pain. Just working on his hips wouldn’t be enough since his hips were the “victims” of this entire unfortunate movement pattern.

In the words of Brooke Thomas, “We become the shapes and movements that we make most of the time.”(2) And those patterns do not go away when we go to a yoga class. If a student of mine is used to hiking her right hip up while walking, she will do the same thing while attempting the tree pose. This is where awareness comes in. If we do our yoga practice on autopilot, we reinforce the patterns that we already have. If we pay close attention to what we are doing, we have a chance to overcome those habitual movement patterns.

This is one of the reasons we repeat each pose a few times before we hold it – it gives us an opportunity to examine our movement patterns and correct them if necessary.

RESOURCES

1. Thomas W. Myers Anatomy Trains: Myofascial Meridians for Manual and Movement Therapists – In-depth exploration of fascia and myofascial meridians with extensive list of references.

2. Brook Thomas Why fascia matters – Free, down-to-earth, fun look at fascia and why it matters.

Wonderful! Yes I am totally in awe and fascinated by fascia, love your way of wording in this article. Nice to be reminded and to remind students that we create patterns and habits through the body “we become shapes and movements we make most if the time” through daily life etc, to remain focused to begin to observe and slowly without force change the patterns over time with patience! A lovely way to say, stay focused observe in class yourself and never mindlessly follow directions. Can’t wait for your next article! Great great stuff!

Thank you Haidee! I agree, we should “never mindlessly follow directions”! After all, learning to pay attention is a big-big part of the practice 🙂

There is scientific research about fascia that you might find interesting. I, too, when I first heard about fascia from Tom Myers and his “chains” was very excited at the potential for healing fascia may have. However, having done some digging into actual scientific research, I have come to realize that fascia has been overly hyped, that lack of real knowledge about it has driven people to make claims about it that simply do not stand up to science. However, as a Yoga Therapist, I am still doing the same things with my clients, and Yoga still works, probably for the same reasons it has worked for thousands of years. It is just not the fascia that we are affecting. I think you have a great article there, and I have written one just like it a while back, and I am not refuting any information you presented. However, I have since then scaled back my enthusiasm for it. I don’t know if the link will show up below, but basically the research reveals that “that the dense tissues of plantar fascia and fascia lata require very large forces—far outside the human physiologic range—to produce even 1% compression and 1% shear. However, softer tissues, such as superficial nasal fascia, deform under strong forces that may be at the upper bounds of physiologic limits.” Meaning, fascia is just too tough of a tissue to be affected by any force we mere humans possess. This research is called “Three-Dimensional Mathematical Model for Deformation of Human Fasciae in Manual Therapy”, and was done by Hans Chaudhry, PhD. You can google it.

http://www.jaoa.osteopathic.org/content/108/8/379.full

Hi Anna! Thank you for your comment and your link – it was an interesting read! I actually did not find it conflicting with what I wrote or what Thomas Myers writes. A quote from the article: “Fascia is dense fibrous connective tissue that connects muscles, bones, and organs, forming a continuous network of tissue throughout the body. It plays an important role in transmitting mechanical forces during changes in human posture.”

That was my point in the post – we have to look at the whole picture. Since I am not a manual therapist, I don’t claim to know whether or not compression produces plastic deformation in fascia. I do know that without fascia our muscles are, well, ground beef, so whenever we talk about stretching the muscle, technically we are talking about trying to affect fascia (it does have some elastic fibers in it, so it has a bit of a give, it just doesn’t bounce back like a rubber band, or something). Anyhow, I will be talking about it this week – what do we do in yoga that affects connective tissue. Please take a look at my next post on Wednesday and let me know what you think!

Thanks, Olga, like I said, there isn’t any conflict, and I didn’t mean to criticize anything, I just shared my doubts about our ability to affect fascia in a clinically relevant way. It does appear that fascia transmits and distributes force in fascinating ways, but so far there has been no evidence that it is abnormal or treatable. R Schleip in his research about those “elastic fibers” established that fascia is contractile to a trivial degree. I guess if it is too tough to “release”, and any elasticity it has is too insignificant, then the answer to the question of whether fascia matters is – maybe not as much as we think. Moshe Feldenkrais, one of Tom’s teachers, repeatedly showed that the so called “physical restrictions” in the body were actually habitual parasitic muscle tensions that could be eliminated simply through a few minutes of low amplitude client-directed movements to bring awareness to those parasitic actions (in other words, exactly what you and I teach to our clients – mild, mid-range movements with awareness!). Love your web site and I look forward to reading your next post.